Watch the Video

The Sega SG-1000 and SG-1000 Mk II were released in Japan around the same time as the Famicom (Nintendo NES) and were the predecessor to the infamous Sega Master System. Here, I take a look at the console, the hardware, software, as well as the back story in creating this epic piece of gaming history.

Way before Sega had any speech sampling attached to it’s logo. Even before the Sega Master System arrived on our living room floors. Sega Executives were concerned. The early 1980s witnessed a downturn in arcade use, primarily in Japan, and at the time Sega Enterprises Incorporated, who in the States, were then a subsidiary of Gulf & Western were one of the top five arcade game manufacturers throughout the world.

Rather than collapsing in panic, Sega noticed an opportunity to expand into the home gaming market, something which a company known as Nintendo had also eyeballed, and in the summer of July 1983 the Sega SG-1000 was launched (not related to the Yamaha guitar, by the way). This happened to coincide with the exact same day that Nintendo released the Japanese version of the NES, known as the Famicom. So although the NES is often compared to the Master System in Western regions, in Japan, Sega’s competing offering at the time was actually the predecessor to the Master System, and was technically inferior to Nintendo’s Famicom system.

The SG-1000 was also released in Taiwan, Australia and some European markets, often distributed and sold under different names. In the States, an unauthorised clone popped up which was able to play SG-1000 games alongside ColecoVision releases. Clearly this was a time before lawsuits were fashionable.

Alongside the SG-1000, Sega also released the SC-3000, which was essentially the same machine, just with a keyboard, to allow computing cross-overs for customers who wanted a seat in both of these upcoming worlds.

Shortly after it’s release, Gulf & Western sold their arcade division to Bally Manufacturing, but retained Sega’s North American research & development operation. Over in Japan, Sega’s management were involved in a buy-out bid & the company was bought by CSK Corporation, a leading Japanese software company. This soon after, led to the release of the SG-1000 Mark II in July 1984. The Mark I had been somewhat of a commercial failure, partly due to the success of Nintendo’s more powerful machine, but also because it was entering a playing field with several other, already released different game machines, including offerings from Takara, Bandai and Tomy, not to mention the American systems such as Intellivison and Atari 2600. In light of this, Sega’s solution (as would become their tradition throughout every generation of hardware), was to stick the hardware in a different case and re-market it.

The SG1000-II sold at the same price as the original (15,000 Yen), but did feature a few hardware tweaks including detachable controllers and the ability to play Sega Card games, which would become common on early Master System releases. You can also see that the case design took a significant step towards the look of the Mark 1 Master System, and even more so when compared with Japan’s version of the Master System; the Sega Mark III. Ironically, the Master System II design would later take a backwards step to that of the SG-1000. Clearly fickleness was a strong attribute throughout the Sega corporation.

As SG-1000 sofware was fully compatible with the MKII, offical cartridge production ran from July 1983 through to February 18th 1987, when the last cartridge game “Portrait of Loretta” was sold. However, Sega did build backwards compatibility into the Mark III, so that this library was not lost on users upgrading to their latest machine, although the cartridges are simply too big to fit into the Master System.

Inside the Box

Inside the box of the Mk2, you find a couple of japanese adverts, featuring some dinky cars – man, I just love Japanese stuff, even if I can’t read it – there’s also a warranty card, an instruction manual depicting you should probably avoid hitting you machine with a hammer, screwdriver, the sun and an, errrm, coffee machine?? The console itself is snugly packed in styro-foam, with the updated SJ-150 controllers housed on either side of the machine (a design which was inspired by Nintendo’s more successful Famicom). In contrast to the Mark I, these controllers are detachable and plug into the back, rather than the front of the unit – a commendable design implementation which almost certainly helped it’s wider success. You also get little joystick nubs you can attach to the D-Pads, but in practise, these are completely useless.

On the top you find an easy to find pause button, a familiar doored cartridge slot, and on the front is your regular power button.

Also in contrast to most modern design, the expansion port sits on the front of the unit and allows the attachment of accessories including the additional keyboard. This keyboard allowed you to effectively upgrade the machine to it’s computer counterpart, the SC-3000, allowing access to various software packages available at the time including a music package and a BASIC interpreter. The keyboard itself is very Sinclair Spectrum-esque, with spongey rubber keys, ear & mic sockets to save and load BASIC programs from and a printer connector, I….. think?

You can also get a variety of other expansions for the console, including a steering wheel (for that authentic driving experience) and “proper” joysticks.

I picked my SG-1000-II up for about £150, including the keyboard, which I consider somewhat of a bargain. I also secured a bundle of cartridges imported from Japan for a few quid.

Technical Specifications

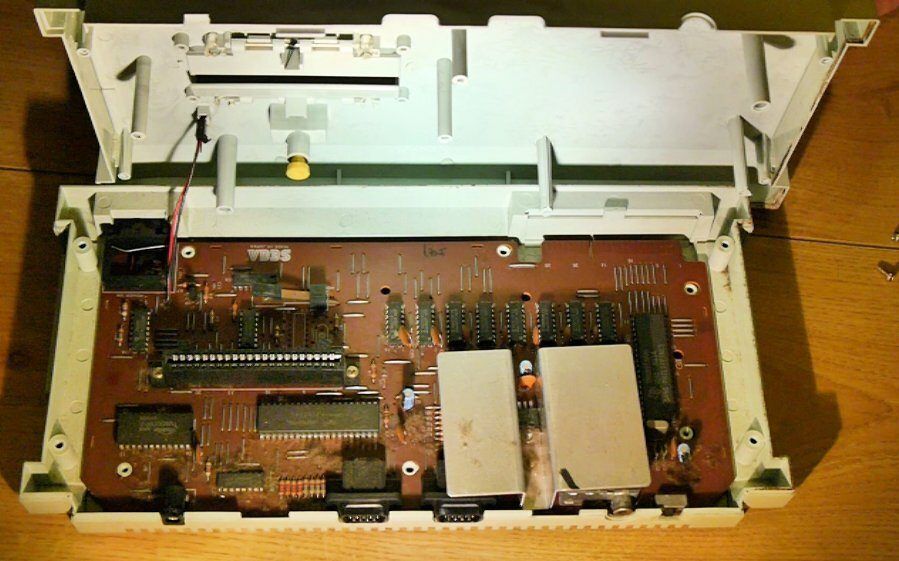

The system is powered by a Zilog Z80 CPU, running at 3.58MHz. Interestingly the SC-3000 ran at 4MHz, and this was the same CPU which would later work it’s way into the Master System.

Video processing is controlled by a Texas Instruments TMS9928A capable of displaying 16 colours.

Sound was handled by a Texas instruments SN76489.

The system provides 8KB of RAM and 16Kbits of Video RAM.

Power is provided through a bog standard 9V DC adapter.

The system has no composite output unlike the Master System (Mark 1, at least), so your only option is the bog standard RF lead.

The machine drew many comparisons with the ColecoVision console in the graphics and capability stakes, and when you realise that the CPU, video and sound chips were identical in both systems, it becomes clear why this was.

Software

Taking a look at the cartridges, you can see that they’re bigger affairs that what later Sega Systems would become used to, but still cut in smaller than the beasty slabs you had to carry to your typical Nintendo Entertainment System.

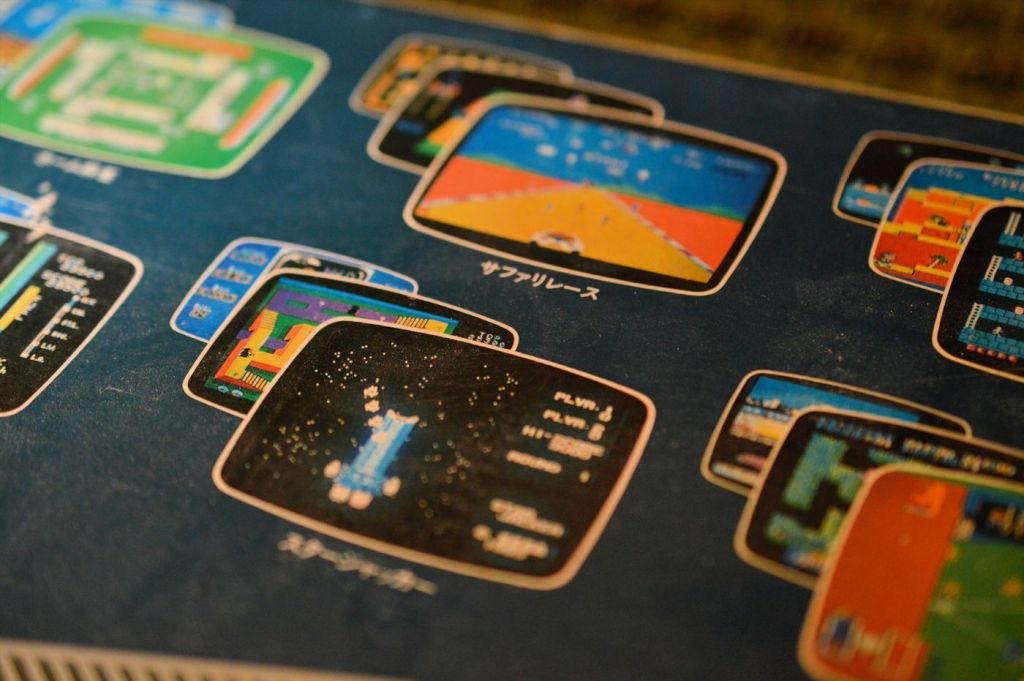

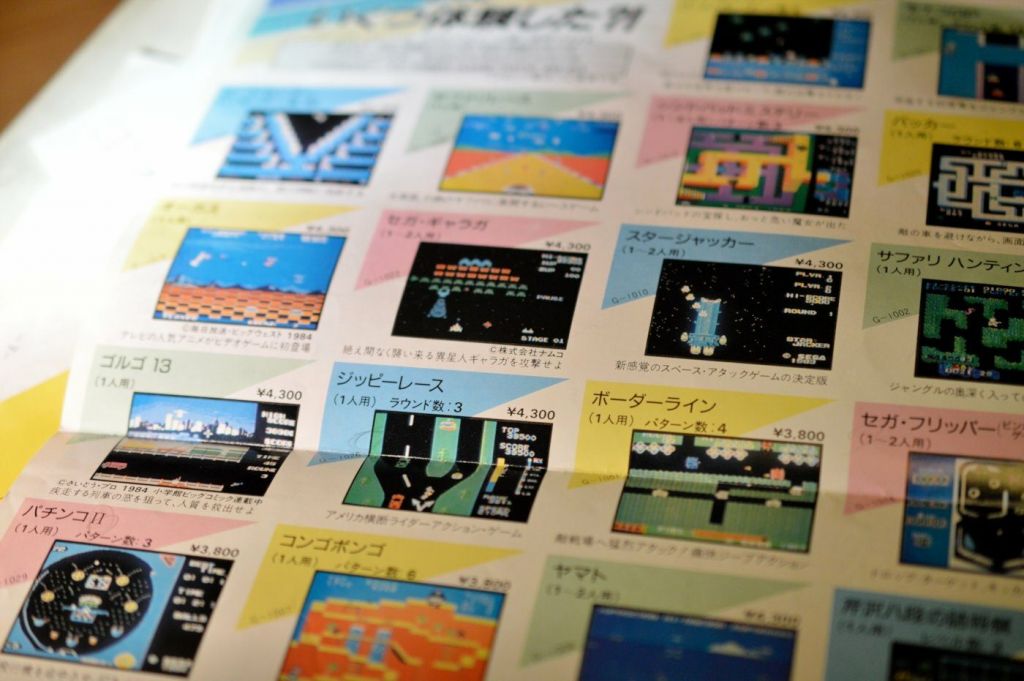

The lifespan of the system saw the release of 68 cartridges and 29, lower capacity Sega Card releases (although we’re only talking a few kilobytes for entire games), which required the additional card catcher accessory to load. 26 of the cartridge releases require the optional keyboard accessory if you’re not using the SC-3000. Titles include;

Monaco GP, which seems to feature Ecto-1, and a jumping F1 car

Dragon Wang, who has the best hump walk I’ve seen, and kicks like he’s trying to turn the oven off

Pitfall 2, featuring Laurel, apparently searching for Hardy

Star Jacker, which I quite liked

Congo Bongo, a Donkey Kong clone with a questionable name, but plays quite well

Sega-Galaga, which is a reasonable attempt at Namco’s Galaga, but with god awful sound effects

Golgo 13, which sees you blasting out train windows to free passengers?? Woah..Shit that guy is scary

Girl’s Garden (Knowing Japan, I suspect that may be a euphemism) – it was the first game to be directed by Yuji Naka, who would go on to create that wonderful blue hedgehog, and features some really nice graphics.

Elevator Action, one of my all time favourites. And check out that double let kick! Woah!

Flicky, which sucks

HERO, which sucks

James Bond 007, which sucks

And Hang on 2, which is surprisingly good. Nah I lied, it sucks, major style.

Music Station actually features some actual music samples, which is frankly, incredible.

Originally all software shipped with both English and Japanese instructions, but following the lack-lustre take up of the machine, this was switched just to Japanese in later releases.

In terms of playability, it’s a slight step up from playing a Colecovision or Atari 2600 release. The standard control pads are very spongy, incredibly more so than a Master System pad, plus having the leads located on the side is actually quite a hindrance. But regardless, some titles such as Star Jacker are actually pretty fun to play, and bar the NES, it still beats most the competition around during it’s time.

Brighter Days

With the Sega Master System (or mark III) being released in 1985, the production run for the SG-1000 series was a short one, but one which allowed Sega to establish themselves in the home gaming market. The improved graphics and capabilities of the Mark III over the NES, coupled with the smart move to allow backwards compatibility from SG-1000 titles, helped Sega gain ground in their home market and even become dominant in some areas where the SG-1000 was never even released, including the UK and Europe.

So then, the SG-1000, although not the biggest commercial success, and not even released in Western regions, was an inevitable part of Sega’s journey. A journey which led to two of my favourite and most played childhood consoles, the Master System and the Mega Drive. So in that regard, I frickin’ love it. Good work Sega.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.