Space Invaders. What a great game, especially for 1978. For designer Tomohiro Nishikado to come up with this concept back then is absolutely mind blowing. Here, we have the first fixed shooter, the first game with waves of enemies and the first game to give most of us anxiety.

The aim is simple, destroy descending waves of aliens as they move closer and closer to your defences and ultimately your laser cannon. If you get hit by one of their projectiles, or an alien itself, you’re dead. But the more aliens you destroy, the faster they descend towards you, and the faster that ominous soundtrack beats into your brain. Interestingly, that gameplay mechanic was actually a limitation with the Intel 8080 based hardware, and the simple fact that more aliens on screen equates to a longer draw time. If you start taking aliens out, there are less to draw and therefore, they move faster. Rather than compensating for this, Tomohiro rather cunningly, just left it as a gameplay mechanic. One which helps make the game, so damn appealing.

Machines like this are so iconic, with their appealing artwork and quirks, like a mirrored internal screen, allowing for the Pepper’s Ghost effect, which makes the cardboard background appear behind the invaders, that these days they’ve been reproduced by the likes of Numskull into these quarter sized replicas. But that’s because the late 70s and early 80s were a golden age of arcade machines…

each one having their own unique hardware, boards, wiring setups, cabinet design, mostly created from the ground up. However, by 1985 the Japan Amusement Machine and Marketing Association, often shorted to JAMMA, had created a new universal standard, designed to make things more straight forward and cost effective for amusement operators.

Before this point, amusement operators would often try to save money by rewiring cabinets themselves. This is why, if you think back, you’ll probably remember all kinds of mish-mashed machines. As long as the controls and screen weren’t bespoke, then you might for example get Golden Axe in an old Bubble Bobble cabinet, or Double Dragon in a Renegade cab, or anything else really. Because the alternative was, the operator would just have to purchase an entire brand new cabinet, screen and all, which got pretty expensive, and cumbersome.

The JAMMA standard then, used a 56 pin edge connector on the board, with inputs and outputs common to most video games, including 5 volt power, 12 volt sound, joysticks with four buttons and analog RGB video. From this point on, any cabinets adhering to the standard, could just have a new board popped in and voila! Golden Axe could be Final Fight in no time at all. Of course, to complete the effect, you’d have to change the artwork, but to us kids, who’s gonna know the difference?!

Of course, deluxe cabinets, with bespoke controls or look would still need to be produced. The likes of Die Hard Arcade, Daytona and House of the Dead do their own specific thing. But most other machines would be JAMMA under their skin. If you look around Barcadia, there are even several generic Jamma Specific cabs, these ones are VideoMasters. This one has Metal Gear, Bubble Bobble, Golden Axe, Frogger, Final Fight. If I look at my stats and find that one of these games just isn’t popular, well, I can just take the board out, get a new one, change the artwork and instantly – and hopefully – I have a more popular game.

But it’s these generic cabinets which caused a bit of a stir in the early 90s, and that’s weirdly because of a piece of Japanese legislation which meant they had to be shipped with a secret game. A game that the general public would never play, but which to all accounts and purposes still had to be a game and it had to be playable.

JAPAN 1990

Japan has always been ahead of the world in terms of electrical wonders. I mean, they had the first wireless telephone in 1912, the first fully electronic television receiver in 1926, they had CDs before us, consoles before us, and so it’s no surprise that they had legislation about electronics before us.

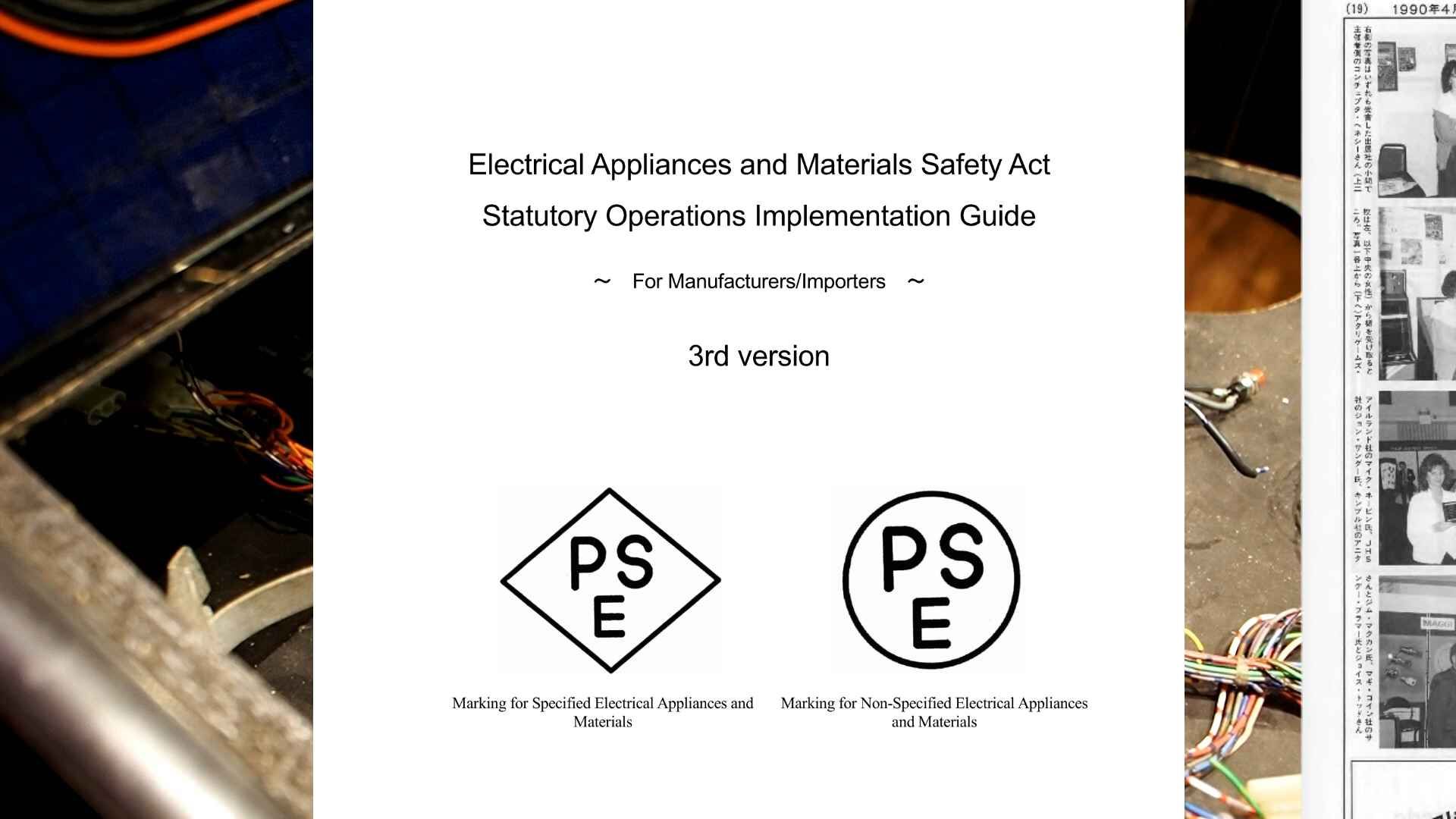

Now, due to syndication the internet is rife with this and that telling you that it was illegal for Japanese companies to sell a cabinet without a video game. That’s kind of accurate, but there’s a little more to it. Previous proprietary and even JAMMA cabinets had already been sold without games, including Sega’s City, Aero City, Jaleco’s Lo-Pro and Namco’s Consolette, most of which look very different to our JAMMA cabs, however, in early 1990, The Ministry of Industry of Japan updated their Electrical Appliance and Material Control Law, specifically in a category called Denki Yoohin Anzenhou and the “product safety of electrical appliance and materials” laws, stamped on goods as PSE, similar to Europe’s CE mark. This stated that electronic goods, and namely arcade machines, had to contain a PCB, the cabinet, a monitor and any other components needs for operation. These would be tested and then need to be shipped out in the same state they were approved. So to comply with this, the cabinets would need something running on them. Without, they would be classified as an “Unfinished Electronic Product” and therefore unsellable. So then, a company selling a JAMMA cabinet, but without a game, well, that would be an electronic device that couldn’t be readily used, and therefore unfinished. So, distributors came up with a cunning plan.

Taito

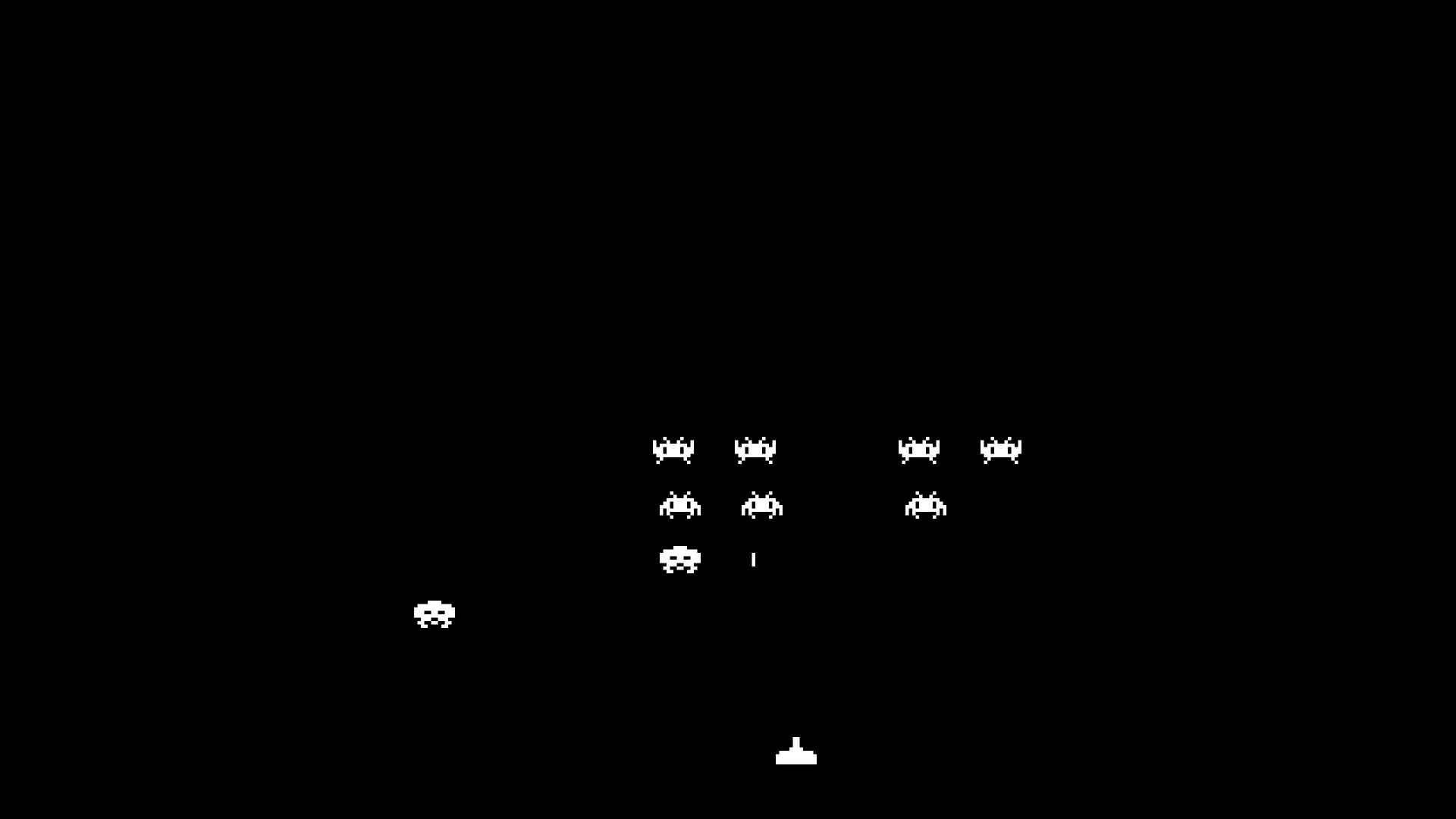

Meet Mini Vader, released by Taito in 1990 with the express reason of completing the JAMMA electronics and making the setup usable. Come on, what other game would you have expected Taito to use? Now, most operators upon receiving this, would have simply removed this board, plugged a proper game in, and carried on with their lives. HOWEVER, Mini Vaders is a playable game, and although it’s no Space Invaders, it has it’s quirks.

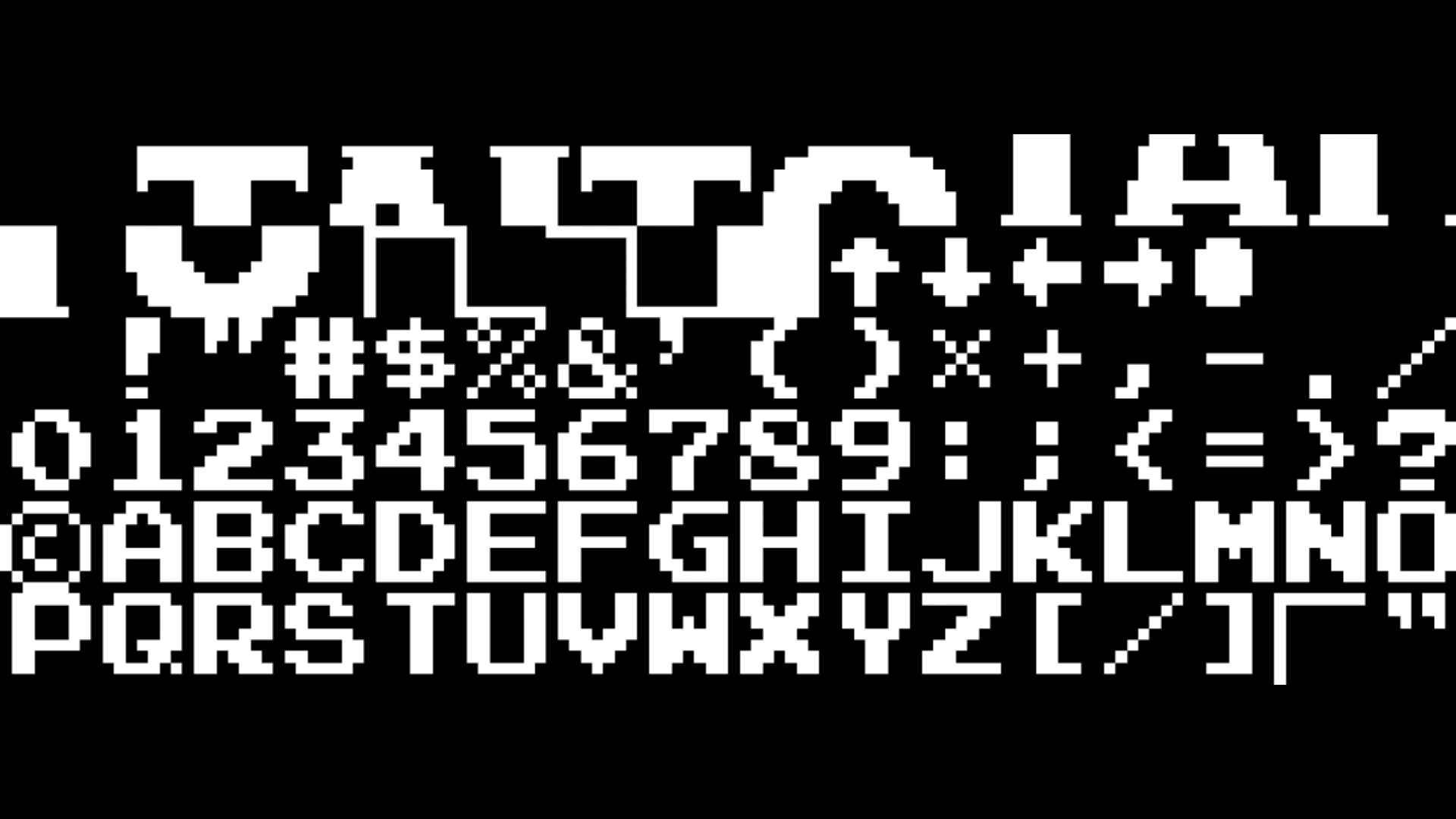

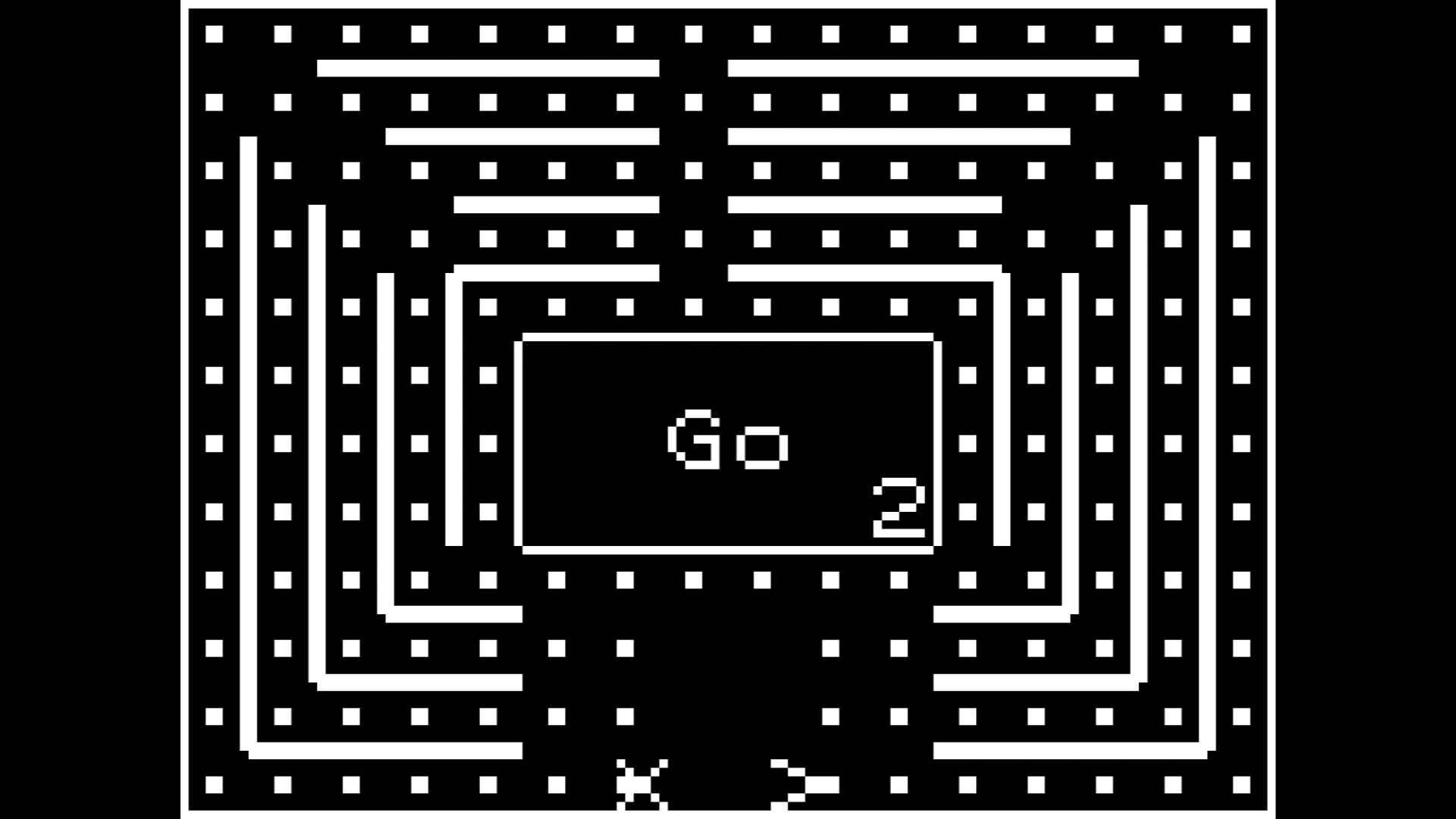

Running from a Zilog Z80 CPU, we are treated to only monochrome graphics here. There is no scoring system. There is no sound. The font has been stolen from Bubble Bobble, as has the Taito logo, which differs from actual Taito logos used at the time.

You may notice that in the first level, there is only one singular space invader also, who doesn’t fire at you. In fact none of the Space Invaders fire at you, they just descend until you die. However, we do still get UFO’s at the top of the screen, not that shooting them does anything other than turn it into the word BOMB, given there’s no scoring system.

Level two gets a bit more spicy though, with 16 invaders of different shapes and sizes. Level three gives us 30 invaders. Level four, 21 invaders. Level five, 20 invaders. Level six, 20 invaders. Level seven, 5 invaders, and level eight, all forty invaders. After that, you get the text “ALL ROUND CLEAR” followed by “GAME OVER”. You can then put another coin in and play again. It should be noted though, that actually, although this lo-fi version of Space Invaders sounds easy, it’s actually quite hard, mainly because the invaders move INCREDIBLY quick. It’s like running an old DOS game on a Pentium.

Ok, so that’s Taito covered. But remember, there were other publishers, and they each had to circumnavigate these laws, and they did so in their own unique ways…

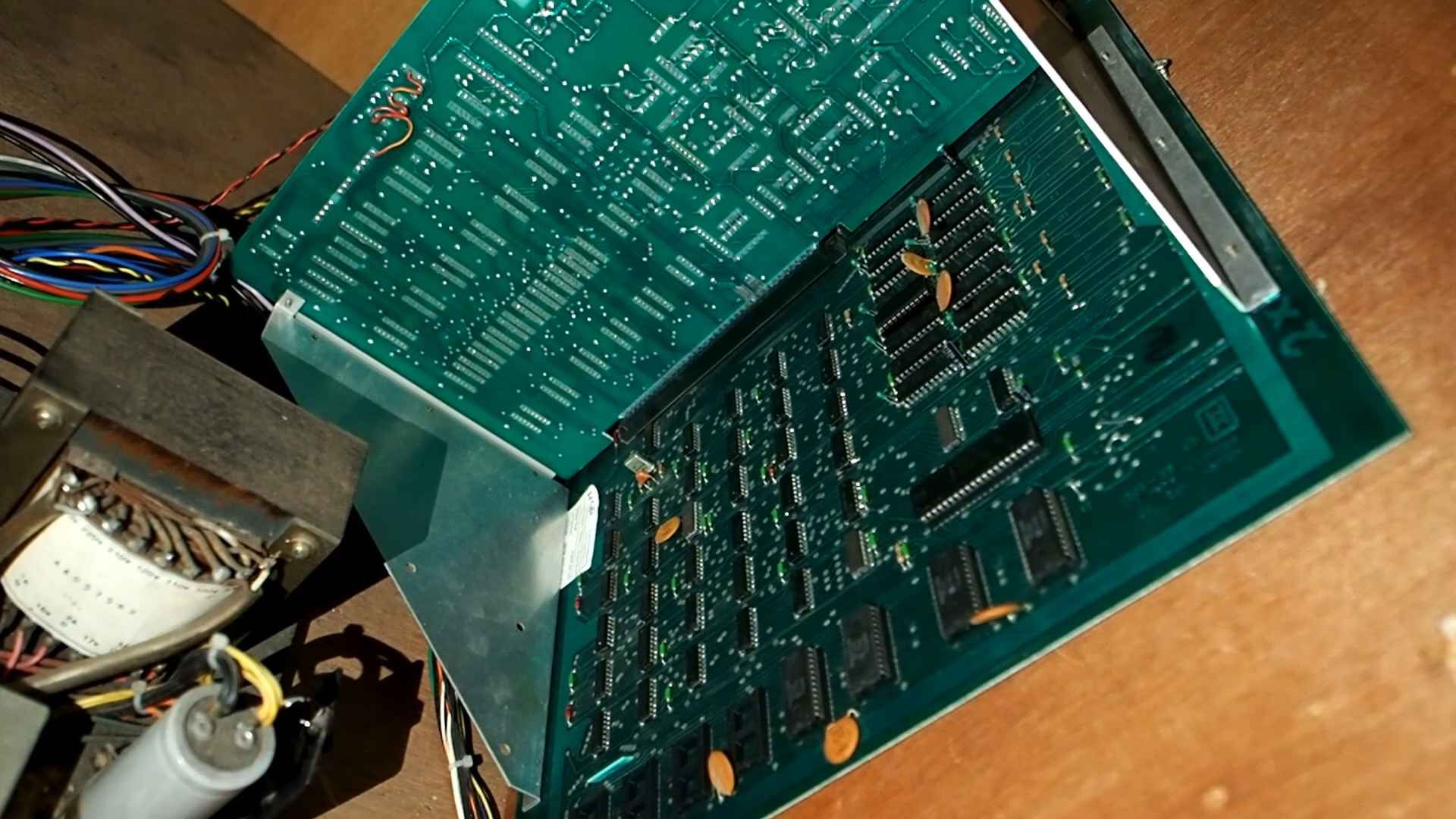

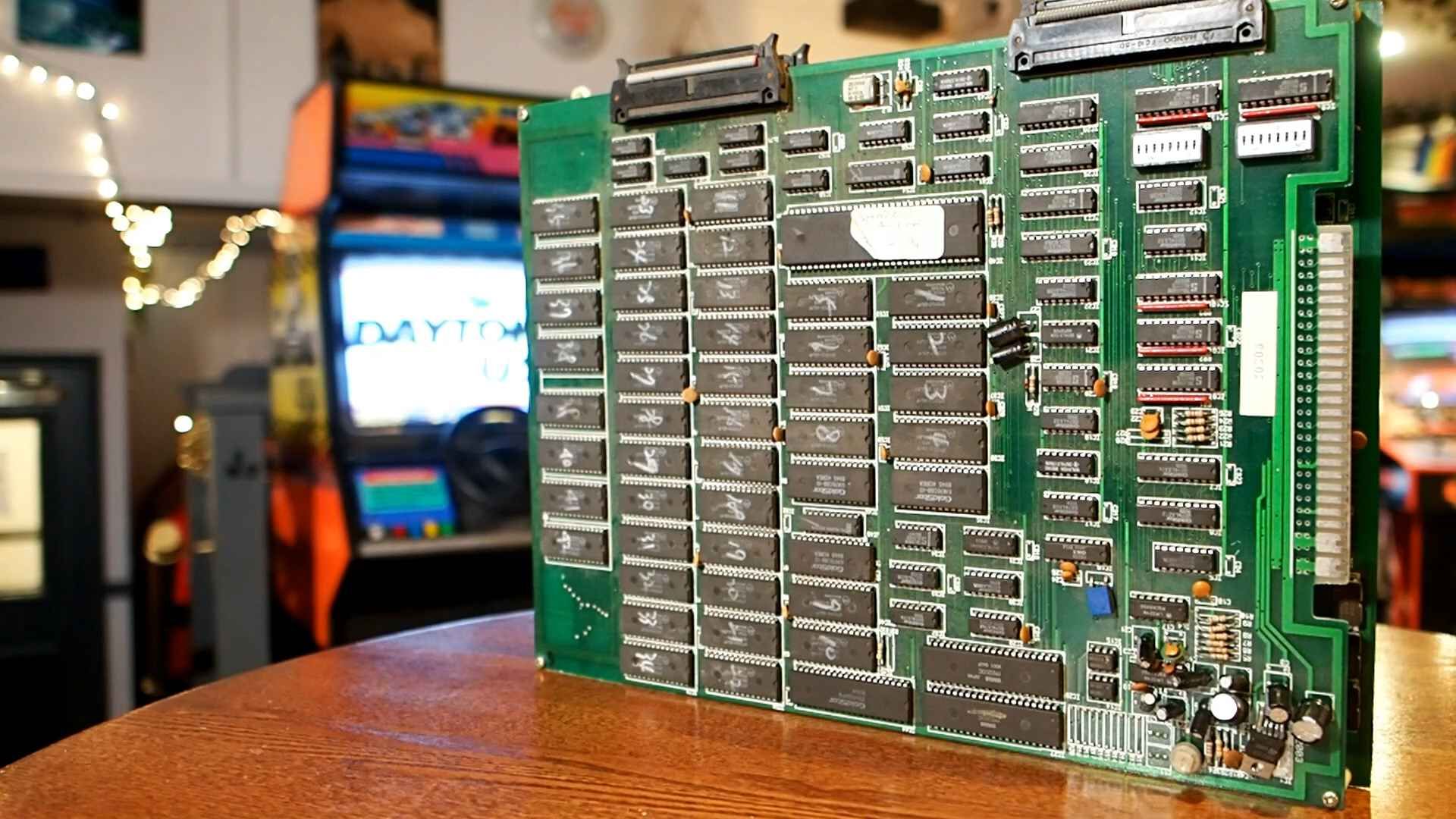

This is Sega’s solution. It’s a JAMMA board made up again, from a Z80 CPU with 2KB RAM, 16KB of ROM and various other chips consisting of NAND gates, NOR gates, OR gates and Six Schmitt-Trigger inverters to name a few. In fact, most of this board is made up from discrete logic. As you’d expect, it’s like Sega were trying to use up old cheaper components, but to all extents and purposes this board is actually a proper functioning computer.

Enter Dottori-kun

Also released in 1990. Now, like Taito, Sega took one of their older games, namely Head On and simplified it.

In Head on, you control a car, collecting dots in a maze, and yes, this actually pre-dates Pac-Man by one year. Collect all the dots by manoeuvring between lanes and avoiding the other cars, through use of your accelerator pedal, and you clear the level.

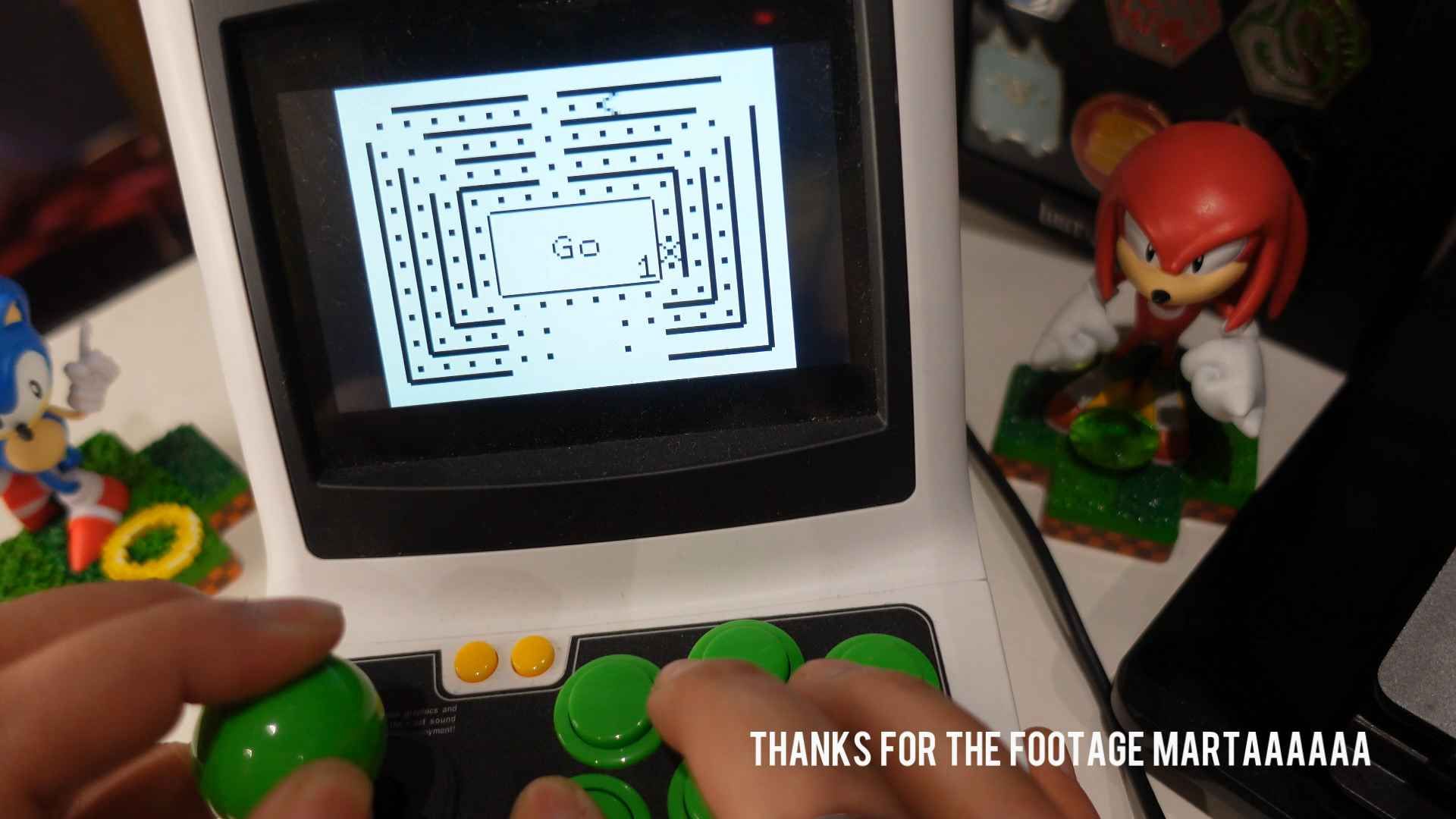

In Dottori-Kun, again everything is monochrome, there is no scoring, there are no cars, instead there is an arrow (that’s you) and an X (that’s the enemy), but the premise is the same. Collect the dots, avoid the X and press button 1 to go faster. If you do happen to hit X then you die, and have to start again from level 1. Every few levels, an additional X joins the board. Unlike Head On, you can’t spin 180 degrees, and if you hit a corner, the game automatically turns for you. However, like Mini Vaders, it gets pretty damn difficult by level 3.

Unlike Taito’s game, the board does however include some test modes. There’s a Memory Test, Input Test and even an RGB colour Test. So that’s nice. Would have been nice to splash some colour in the game too, but hey, you can’t have everything I guess.

But the test modes demonstrate the thing about this little board, like I said, it is basically a functioning computer; in fact a gent by the name of Chris Covell took the board, programmed a new ROM and made several much more advanced games for it, so that’s pretty cool.

You can also find this game on the Sega Astro City Mini, released in 2020, with inverse colours. A nice touch.

Alright, who’s next?

Konami! That’s who.

Released a little later than the others in 1991 to coincide with the launch of their Domy Jr cabinets, all you have to do is look at the board to see how much more advanced this fella is. Although still running off a Z80 CPU, there is an Audio DAC here and 32KB of RAM; enough memory to shake a 1970s stick at.

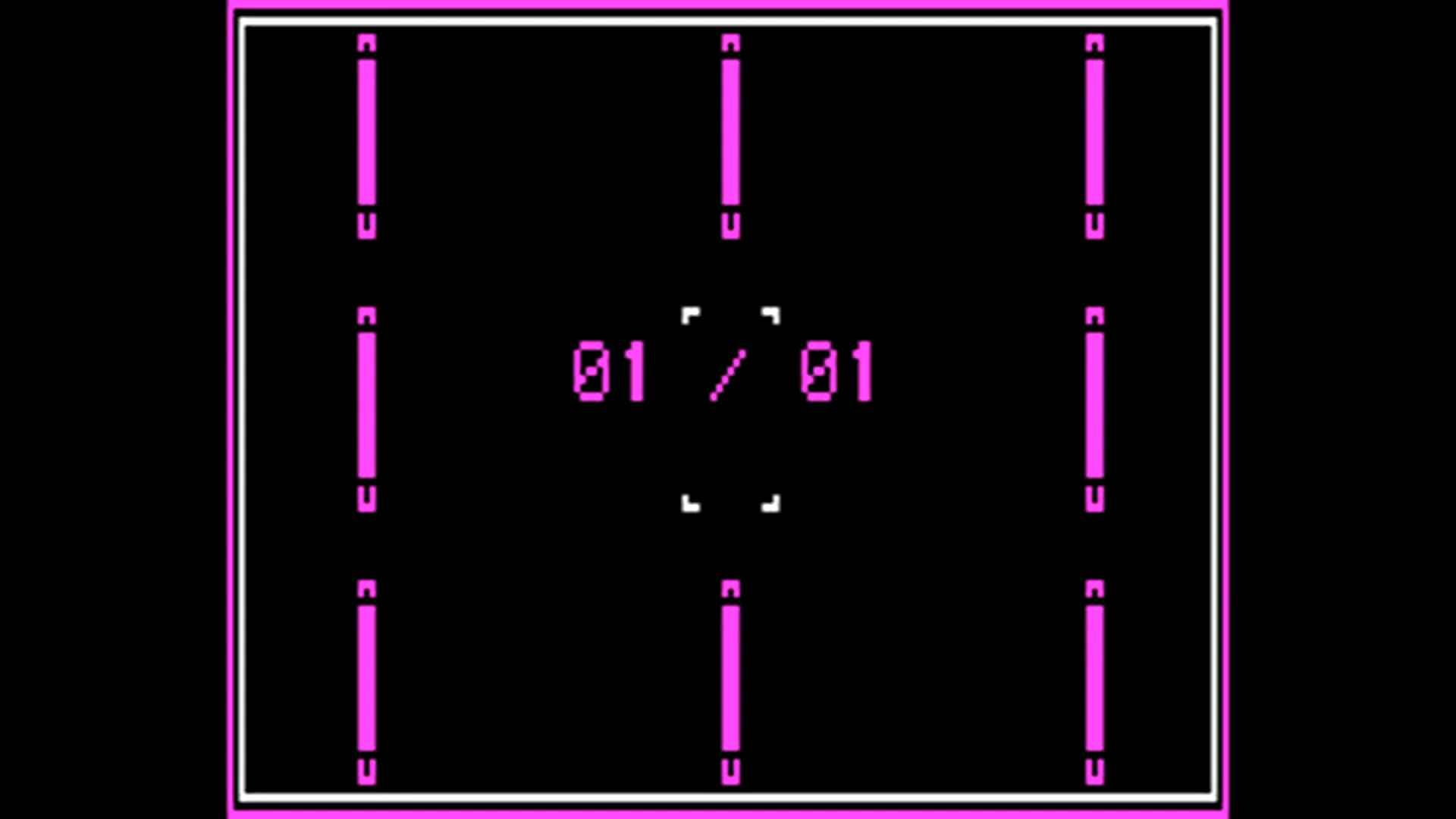

Welcome to Mogura Desse and a WORLD OF COLOUR. Rather than just yanking one of their ancient games out of the bag, Konami decided to make something a little more impressive for their new line of universal JAMMA cabs.

Here we’ve got a whack-a-mole type game. Simply move the joystick into the correct direction and hit one of the fire buttons to hit your mole. We even get a kind of scoring system, with this success ratio. Nice. I probably would have played this had it been released as an actual arcade game tbh.

There are very few of these actually in the wild, and that’s because, apparently Konami would buy these boards back from the operator for 15,000 Yen, to reuse in another housing. Now that’s pretty smart, and definitely minimises the waste of just chucking boards in the bin.

Konami would also release Target Panic in 1996 for their Windy Cabinets, which just offered a cheap, monochrome target practice game. In complete contradiction to the investment they made with Mogura Desse.

Namco

And so we move to the best of the bunch. Namco’s Battalion board, released in 1993 to coincide with their new Exceleena cabinets. Now clearly it’s still a very simplified video game for 1993, but it’s actually a fully functional game.

Based on Tank Battalion, released in arcades in 1980 and converted to the MSX home computer, you control a tank and must destroy twenty enemies each round. The beauty here is you can also destroy the playfield, something that was fairly unique in games around this time.

The TestPCB version is very similar, apart from the huge Score/Stage/Remains section in the top centre, which you simply work around. Like the original we get scoring, we get various maps, and we get zooming effects. Yeah, trippy shit. But, but, in addition to the original, we also get scrolling effects. Yep, you can scroll around a bigger map, which is actually pretty sick.

And that mostly completes our line up of these secret arcade games that really, only amusements operators, and electrical testers got to play. They’re quite rare to get hold of these days, mainly beacuse they were just chucked in the bin.

Other Vendors

But, but, you may ask, what about other vendors, like Capcom, Jaleco, SNK, etc… What did they do? What boards did they provide.

Well, there may have been some other test boards knocking about, but also, a lot of machines were just given an old board. Konami did this with the game Mr. Goemon for a while, hence why their test board was released later. Namco did the same, and it’s likely other vendors did too. If you’ve got the spare boards, it makes sense to use them, right?

Until next time, I’ve been Nostalgia Nerd. Toodleoo.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.