Now, I’m not one to go on about Clive Sinclair and his associated products….. alright, so maybe I am. But even given that, the ZX80 and it’s better selling successor, the ZX81 are tremendously important pieces of the home micro jigsaw puzzle. Without them, we’d probably all be still stuck in the 80s, driving around with permed hair in Audio Quatro’s, Renault 9’s and trying to work out what these fangled Commodore things from across the pond were.

Essentially, without Sinclair we’d be behind the times as Bulgaria.

So we all owe a huge debt of gratitude to our lord commander and his fine creations… and to honour this, let’s all take a minute’s silence.

*cue loading screams*

God! Every bloody time.

Production

Ironically, the ZX81 didn’t feature the iconic loading sound when feeding bauded data from your WHSmith tape deck into the tiny door wedge moulded computers, and the banded lines were actually a interference quirk as the video signal was hooked up to the same ULA pin as the tape output. Still it’s a nice effect. But back in 1980, these machines actually didn’t feature a lot of things we’d come to associate as standard parts of the 80s micro, and other than their earliness on the scene, the main reason for that was PRICE. These were machines designed to come under the golden price point of 100 English Pounds.

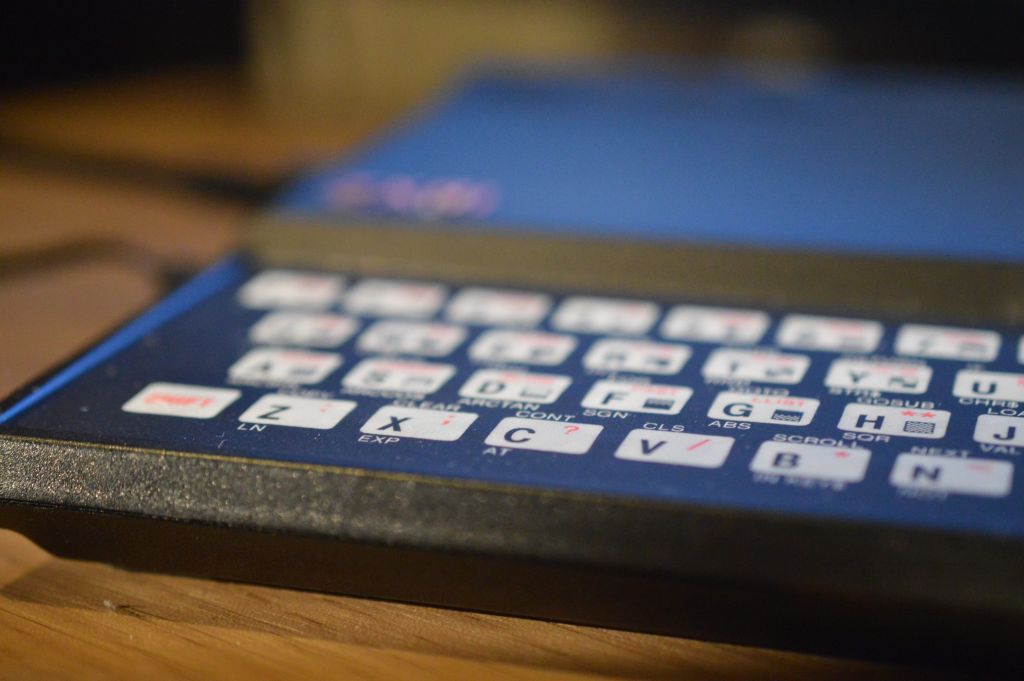

Back when Sinclair Research was a glint in Clive’s eye whilst managing his previous company, Sinclair Electronics, Clive had dreamt of an affordable home micro that everyone could buy into. It wasn’t until that company failed and Clive had started up his new enterprise that this vision was made a reality. Following on from a home computer kit, called the MK14, Clive released the ZX80. The first home computer available in the UK for under £100, ready built (and only £79 in kit form). The machine was based around the Zilog Z80 CPU and utilised readily available TTL chips. To keep costs down the case was vacuum moulded and a dead feeling membrane keyboard was utilised – although many replacement cases and even stick on keyboards sought to remedy this. The ROM lacked floating point arithmetic and the machine’s video output was half based in software and therefore driven by the CPU; this meant the screen would literally cut out to register key presses. Never the less, the system sold 100,000 units and kick started the UK’s home micro scene during it’s 1980 launch.

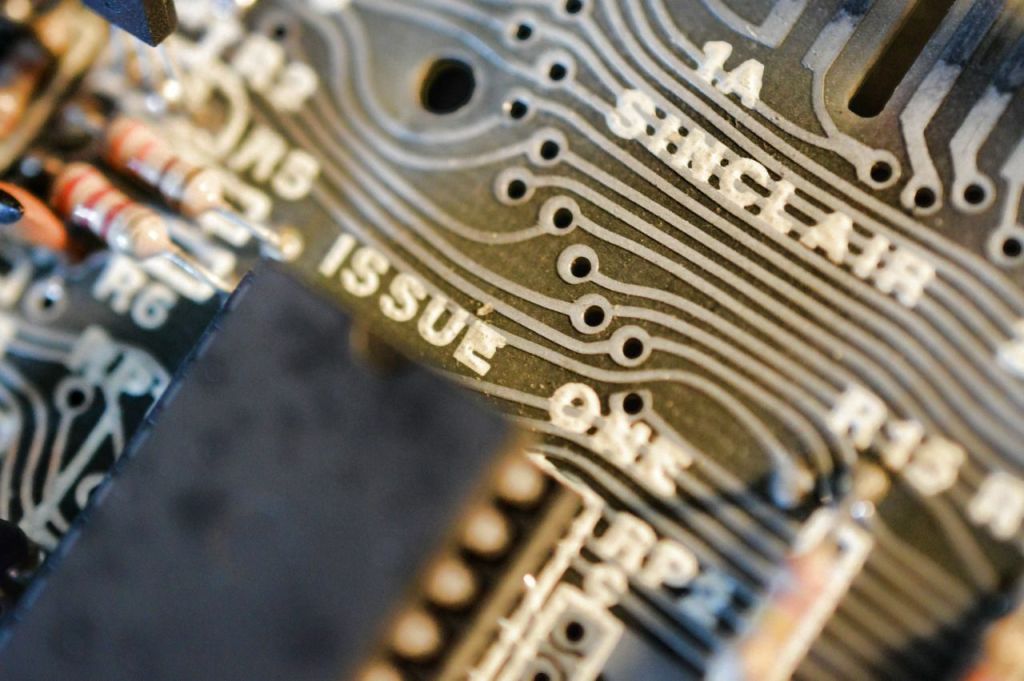

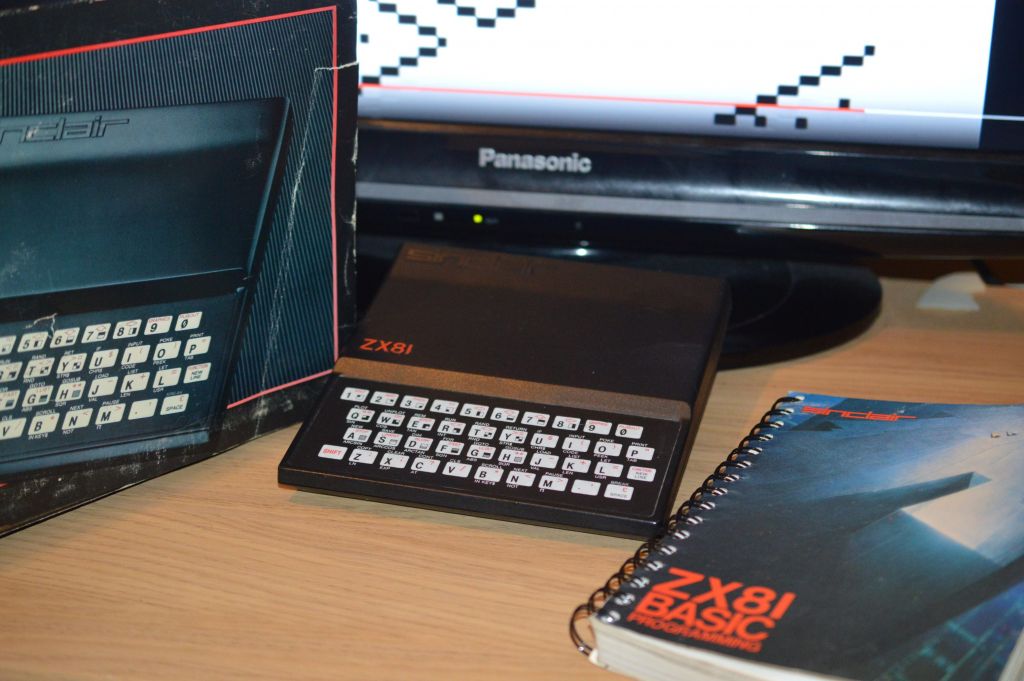

Only a year later, Sinclair, or more accurately, chief engineer, Jim Westwood and his team had developed the technology enough to squeeze the ZX80’s TTL chips into a semi-custom ULA package. They had also incorporated a NMI generator which allowed the hardware to operate in slow mode and therefore stop the screen flicker on key presses. The ROM was also expanded from 4 to 8KB by a company called Nine Tiles, allowing floating point arithmetic, new commands and additional devices to be plugged in. Although the new ROM, allowing decimal points did create an error in the form of the square root of 0.25 being returned as 1.3591409 rather than .5, as it should be.

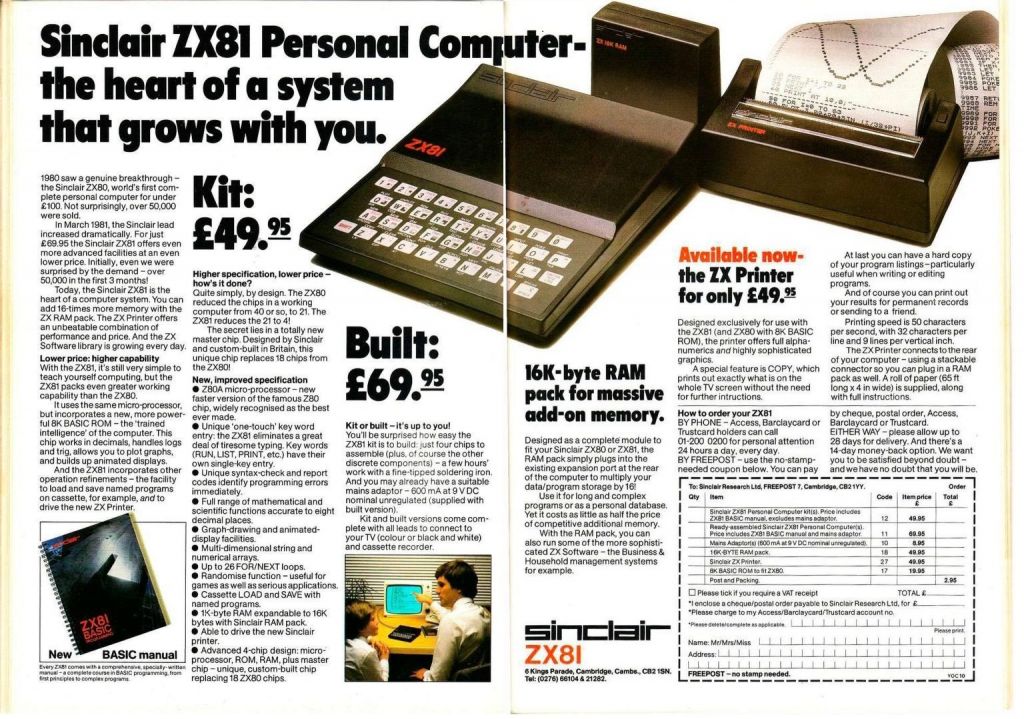

To top it off, Sinclair also splashed out on a black injection moulded case, although retained the membrane keyboard. The result of this was the Sinclair ZX81, sold at an even lower price than the ZX80 at just £49.95 in kit form and £69.95 fully assembled (this equates to about £250 in today’s money). The dimensions of this tiny little package are just 6.6 inches by 1.6 inches high, and it weighs just 350 grams (note I’ve mixed up both measurement systems there to keep everyone happy). Sinclair was always very keen on design and this particular one brought it’s designer, Rick Dickinson a design council award.

The ZX81 had 1KB of base memory (the same as the ZX80), but was expandable to 64KB using plug in RAM packs on the back – which notoriously needed sticking on with blu-tac to prevent them falling out with the slightest jiggle and – at worst – frying the motherboard.

Graphics were provided at 24 lines x 32 characters, or 64×48 pixels in graphics mode. These modes were output using a standard RF plug which you could tune into your television. The output is monochrome only.

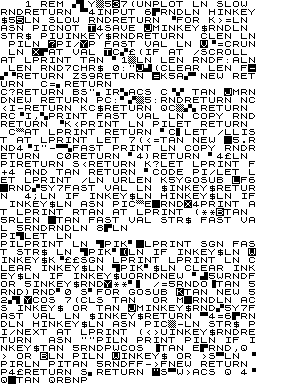

The machine included Sinclair BASIC as it’s standard language and operating system. The BASIC commands were accessible using short cut key functions, which could be accessed using a variety of shift and function key pressings. This saved memory as an entire basic command could be held in one ROM referenced character rather than several if typed words were utilised. Programs are loaded into and saved at 50 baud using the EAR and MIC sockets hooked up to a standard cassette recorder.

Power is provided by a 9V DC adaptor, some of which were recalled due to overheating on early releases.

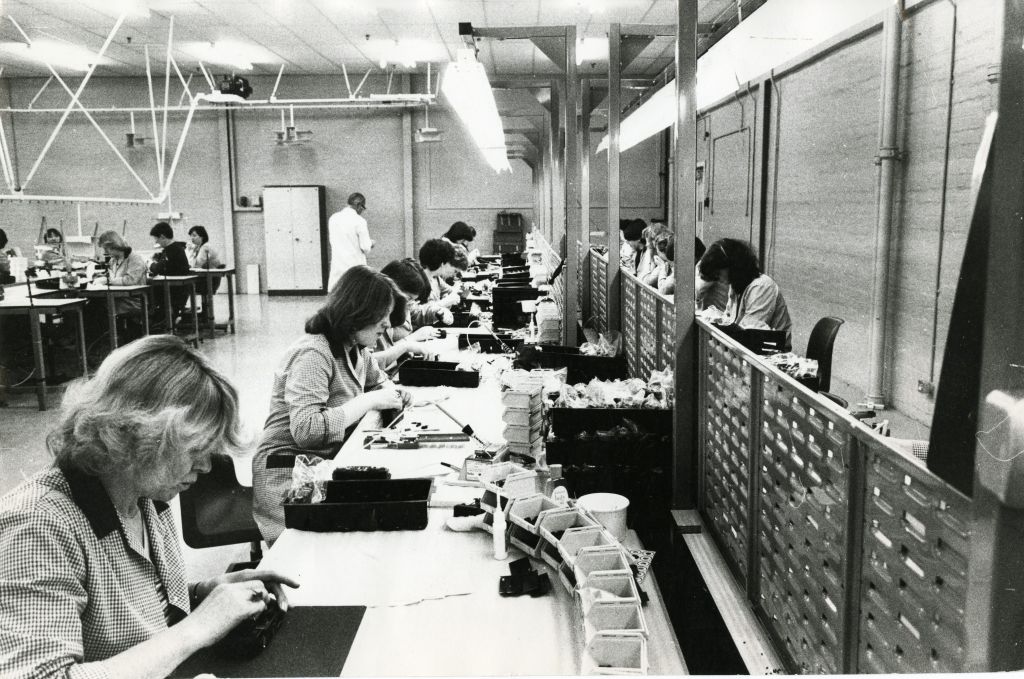

Launching on 5th March 1981, initially (as with most Sinclair products) there were manufacture issues with the company tasked with it’s production; Timex Corporation from it’s Dundee factory. This meant that it sometimes took up to 9 weeks to meet the mail order demand, although ZX80 owners could simply upgrade their machine through installation of a £20 ROM chip.

Even with the initial supply issues, the ZX81 was the first mass market home machine that could be bought from high street stores, with the previous ZX80 only available through mail order. This increased access, and lower price, coupled with the success of the ZX80 meant the ZX81 would sell over 1.5 million units before it was discontinued in 1984. Now, back in 1981, this was a massive number and it lined Sinclair’s pockets enough to go on and produce the Sinclair Spectrum in 1983, but if you want to know more about that you can watch my 3 part review and then forget about this shameless plug. With such high numbers however, came reliability issues, and stores such as WH Smith were known for ordering a third more machines than it sold, simply so it could provide replacements for disgruntled customers. Many of these problems were later attributed to the problematic power supplies.

Marketing

Sinclair’s strategy for wooing potential buyer, was a clever one. What we may perceive as the machine’s weaknesses today, were flaunted as huge selling points at the time.

Before even the high street availability, Sinclair would often take out huge advertisements in popular magazines to appeal to the casual buyer and hobbyists alike with features such as the memory saving keyboard commands marketed as “eliminating a great deal of tiresome typing”. The machines limited ability was advertised as being the ideal machine to ease your way into computing, with the ability to add expansions as your knowledge grew. This was even aided by supplying the “Complete course in BASIC programming” manual written by Steve Vickers to poise the unit as something you could just order and then learn. The public saw these machines as a great way to understand this emerging technology whilst jumping on the gaming bandwagon for the youngsters in the house, and that’s exactly what Sinclair intended.

Sinclair himself became a focal point, adding a human face to the business, with Sinclair Research portrayed as a small British company taking on the Japanese and American giants. This image was played on with “Uncle Clive” taking interviews and featuring in adverts throughout the 80s.

The main attraction however, was that low price. The ZX81 had been designed to meet a £70 price point, as the ZX80 had been designed to meet £100. This price was touted against machines such as the Commodore Pet and Apple II Plus which was £630… 9 times the price of Sinclair’s Micro. The price which was based on the experience curve technique – that a product will be more profitable selling at twice it’s cost than three times – was the main reason the UK population was ahead of the Micro curve compared to the rest of the world.

Reception

The technical shortcomings of the micro were obvious, but this didn’t deter people, nor did it prove to be a problem for those who bought the technology. Remember, this was at the start of the micro scene, so many people didn’t know what to expect anyway, and by the time they’d worked out what to do, either it was time to upgrade, or they’d just packed the machine away in a cupboard.

The 1KB base RAM was pretty limited, and offered a challenge for would be programmers, with a full screen already consuming up to 793 bytes, system variables consuming 125 bytes, leaving only a few bytes for the actual program and any stacks needed on top of that. This didn’t stop games like the remarkable 1K ZX Chess being released however, which packed a working game of chess into just 672 bytes, AI opponent included. For other games, the 16KB expansion pack came in handy and was a very popular add on.

Either way, many people cut their teeth on Sinclair’s BASIC, and it was from this resource that we end up with so many of the ZX81’s game pool. Let’s dive into some of my favourites;

Games

3D Monster Maze

1K ZX Chess

3D Defender

Flight Simulation

Volcanic Dungeon

Cetipede

Crazy Kong

The Gauntlet

Amazingly Dragon’s Lair was recently converted for the ZX81 by ex-Ocean coder Jim Bagley, squeezed in 32KB of memory and feeding from an ZXPand SD Card adapter. It might be using new technology to feed the data, but it’s still a humble ZX81 going the work here. AmaZZXXing.

Wrap Up

There was a sound expansion for the ZX81, however, most software was noise free, as the base hardware even lacked an on-board speaker. However through it’s life clever tricks came to pass including clever use of switching between FAST and SLOW modes which which could induce tones in the video signal and thereby creating some crude sound synthesis. It was even possible to trick the system to display high-resolutions of up to 256×192 through mode switching.

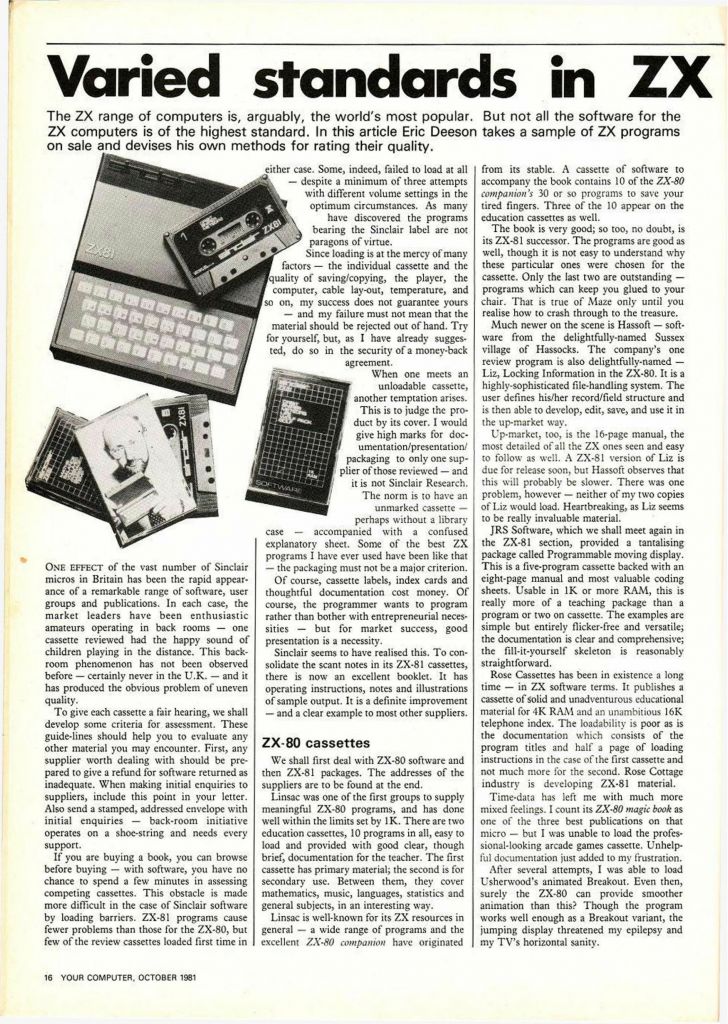

Thousands of ZX81 programs were published, either as printed listings in magazines such as Sinclair Programs or on published cassettes from a number of upcoming software houses and bedroom coders, and this is the exact place we get amazing concepts like 3D Monster Maze. Psion, who would continue working with Sinclair produced the aforementioned Flight Simulator and ICL created over 100,00 cassettes in less than three months

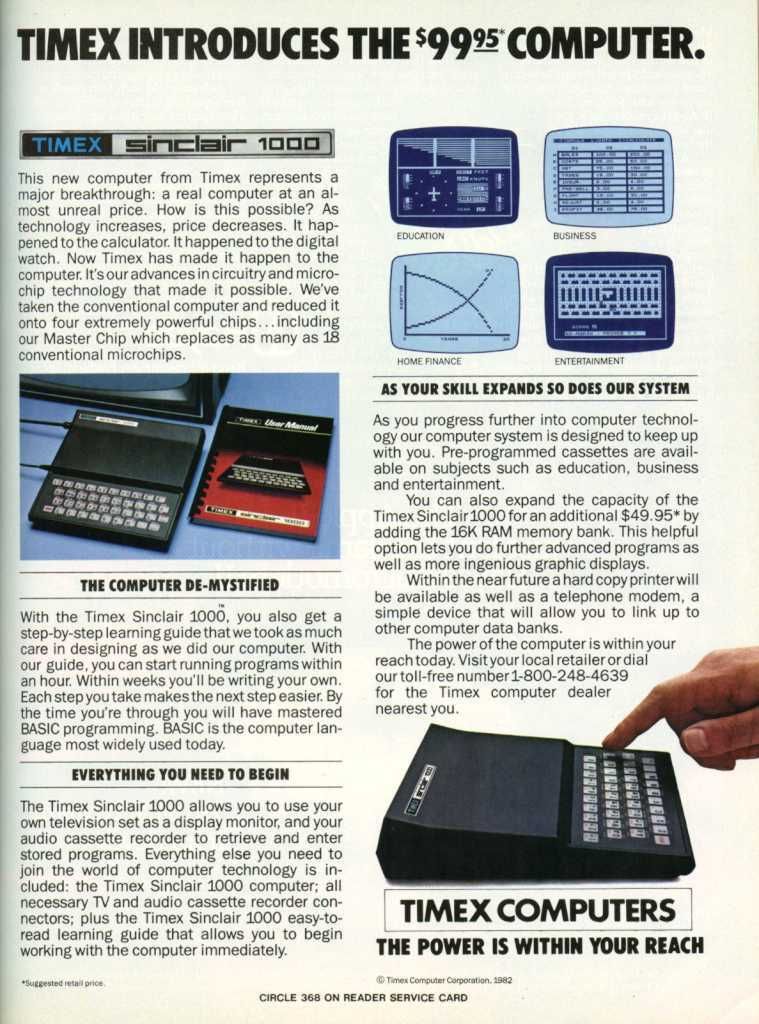

The machine was also marketed in the States for just under $100, and although some were sold, it failed to perform in the same way that it was received in the UK. However it did well enough for Timex to licence the design as the Timex 1000 and try and sell re-branded versions..

these versions initially received huge interest, selling over 500,000 machines in five months and gaining Sinclair over $1 million in royalties, however despite the Timex versions increased 2KB of memory, late delivery on RAM pack upgrades, left many consumers disillusioned with the lack of software the machine had to offer. It also became evident that the US market was more interested in pre-packaged software and games rather than education and learning BASIC programming, and the upcoming VIC-20 solved both these concerns.

Other unofficial ZX81 clones would appear in Brazil, China and Argentina, and some even improved on the hardware.

Throughout it’s life, a vast line of expansions and printers (such as the crude but cheap “Spark” printer which used black aluminium paper to zap text onto) came out for the ZX81, and ultimately the machine paved the way for the incredible Sinclair Spectrum launched in 1983. The machine had a massive impact on the UK market and it’s legacy lasts in the UK development scene which is still thriving to this day.

As for Sinclair, the companies profits rose from £818,000 to almost £9 million after the ZX81 launch and Clive became one of the highest profile businessmen in the UK earning him a knighthood and Young businessman of the year in 1983.

Arise Sir Clive. You deserve it.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.