Watch the Video

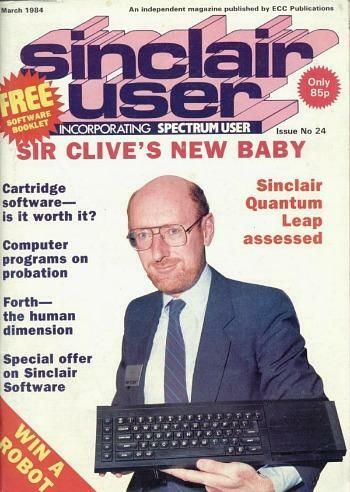

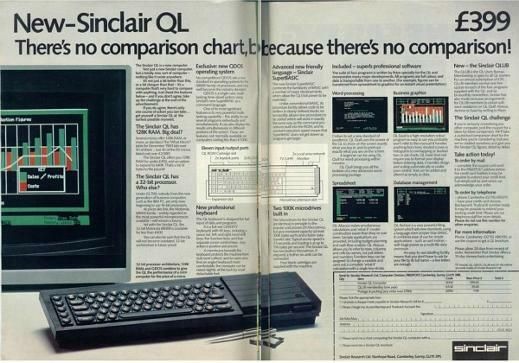

The Sinclair QL was seen by some as the successor to the Sinclair Spectrum, but in reality, it was aimed at the professional, business and serious home user markets. Launching in January 1984 by mail order (albeit with a several month shipping delay), the QL (standing for Quantum Leap) was touted by Sinclair themselves as the solution to fend off IBM, Commodore, Acorn and Apple, who had or were soon to be releasing, more professional systems.

Sinclair was a name of varying association through the 60s, 70s and 90s. Starting in the 60s, Sir Clive, or just Clive as he was known then, introduced the world to a series of breakthrough micro electronic devices through Sinclair Radionics Ltd. Out of what was essentially a back yard shed, Sinclair began to produce components for hi-fi and scientific instruments, gradually building up the business, whilst at the same time making ever smaller, and somewhat revolutionary devices. However, as the radionics company began to fail, even with government assistance, he started up a new company, Sinclair instrument Ltd, in August 1975 and launched the world’s first digital watch, however like some of Sinclair’s earlier products, there were reliability issues, coupled with a terrible battery life.

From there Sinclair’s new company went through a few more name iterations before launching the ZX80, ZX81 and ultimately the Sinclair Spectrum throughout the early 1980s under the name of Sinclair Research Ltd. The Spectrum was a huge success and really introduced the UK to the world of home micro-computing. However ongoing competition with Acorn and Commodore drove Sinclair with a desire to break into the professional market place, and it’s from this place, on January 12th, 1984 when we arrive at the Sinclair QL. The QL standing for Quantum Leap – a name conjured to describe the technological leap. A system aimed at serious home users and business professionals, and launched (and I’ll use that word lightly) exactly 12 days before Steve Jobs would announce the Apple Macintosh.

Now, you may have noticed from my other videos that I have a particular fondness for obscure & plight bound machines, particularly those which failed to make it in the early micro computing world. I think it’s because of their untapped potential… a lost relic from a forgotten age… or maybe just because they tried so hard, and deserve some recognition. Either way, the Sinclair QL is no exception. In fact, in many ways, it’s the leader of the pack.

If you’ve watched the BBC Dramatisation Micro Men (which I whole heartedly and repeatedly recommend), then you’ll know that Sinclair always wanted his products to be viewed as elegant, professional & pioneering, and even though the Speccy sold tremendously well, the film shows him somewhat pained that the machine was only viewed as a low end games machine, hence his inspiration for the more professional QL. The reality however, seems a little more murky. In a fairly recent interview with David Karlin, who was the QL’s chief design engineer, it appears that although many at Sinclair wanted the machine to be aimed completely at business and professional use, Clive may have seen the machine as just a more powerful Spectrum replacement. And although most decisions were made by Clive himself and Nigel Searle, who was the MD of the business; This slight contention may have contributed to slightly muddled marketing and explains why the machine has a TV modulator (if a pretty blurry one). In any case the QL was touted as a competitor to fend off Amstrad, IBM, Apple and Acorn in the professional world. This is evident in the famous advert showing Clive leaping over several higher cost competitor machines.

The QL was launched on 12 January 1984 at £399 by mail order, and when I say launched, it was done in the true Sinclair fashion, with orders taken immediately on a promise to deliver within 28 days. In reality, there wasn’t even a finished prototype at this stage, and the first machines began to ship in April at a slow and steady pace. However due to this apparent rushing, the first machines were plagued with problems. Some had half the ROM held on a dongle plugged into the back, others had firmware bugs in the built-in SuperBASIC language and most suffered from unreliable Microdrives, which were chosen due to their lower cost over floppy disks but higher speed than tapes. These problems tainted the initial reputation of the machine, but in reality it just wasn’t well suited for the business world. The Microdrives were non standard, the keyboard was uncomfortable and most people associated it’s look with the soon to be released Spectrum+ model, and therefore cast it’s professional credibility aside.

High street sales of the QL began in August 1984 – the same time as the QL branded Vision monitor was released -, but yet only a few months later, the QL’s price was halved to £199 in the hope that it would lure more home users, however given the lack of games available for the platform, most opted to stick with their trusty Spectrums, or just upgraded to the Plus model released later in 1984. You can see how similar the aesthetics of these two machines are.

Hardware

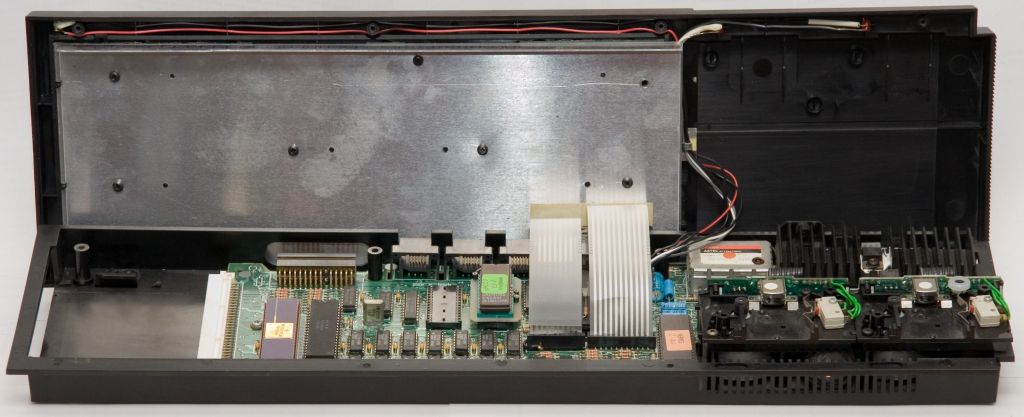

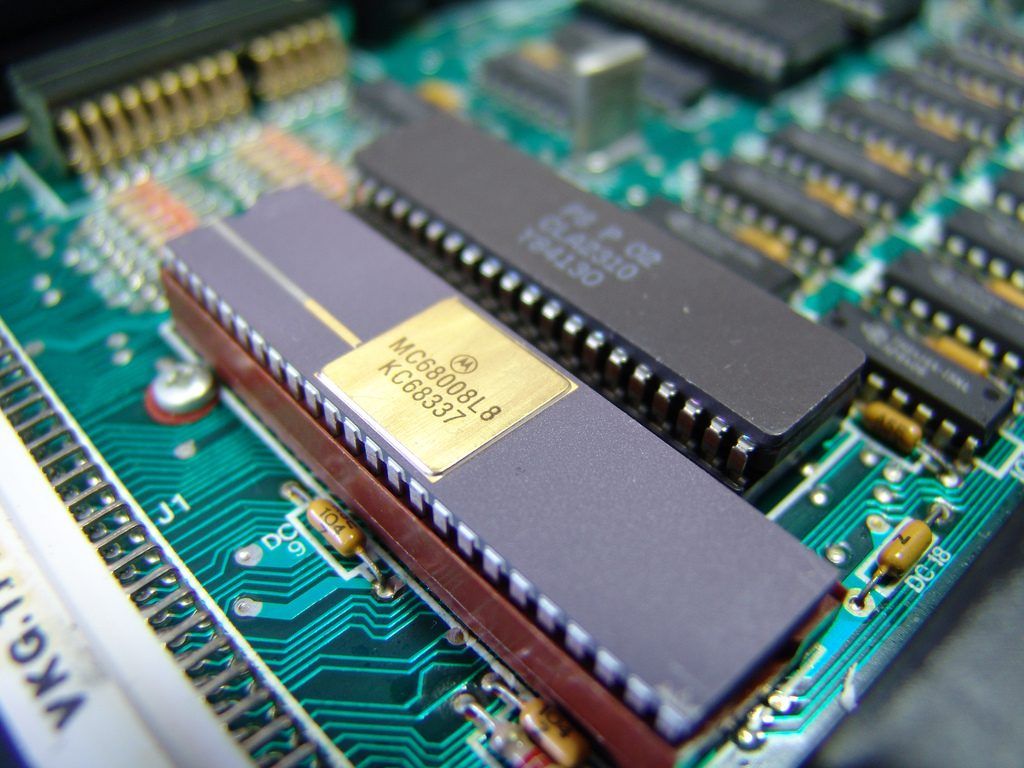

Internally, the QL is based on a Motorola 68008 running at 7.5MHz. Essentially this is a cut down 68000 found in the Atari ST and Amiga 500, with a 16 bit internal architecture, but only an 8 bit address bus. Even so, this drastic switch from the Sinclair Spectrum’s 8 bit Z80 processor meant there would be no backwards compatibility with the massively popular gaming machine. This, of course wiped out a massive opportunity for the machine to have an huge established software collection.

The machine sported 128kb of RAM, which was expandable to 896kb and for storage, made use of the two built in Microdrive units. One essentially for loading and one for saving work to.

Now, although these Microdrives were far cheaper than the new, fangled floppy disks, especially if you lack Alan Sugar’s haggling skills, they were notoriously unreliable, until Samsung took over their manufacture, and the data format wasn’t even backwards compatible with the Spectrum’s Microdrive peripherals, so even if you’d saved some documents on your Speccy, there was no way to open them on the QL. This really was like pissing over the path you’d just laid for yourself. The tapes themselves – or wafers, as they’re known – are essentially like tiny 8 track tapes. They hold a 5 metre reel of tape which spins at 30 inches per second against the machine’s read/write heads. The entire tape can be span within 8 seconds with data read at 15kb per second. For the QL, each tape can hold 100kb of data, although this can be increased slightly by spinning though and formatting the tape a few times, which stretches it slightly (now to me this sounds like the microdrive version of punching a notch in double density 3.5″ disks to make them high density – a useful, but error prone solution). The tape itself spins only in one direction, with the tape brain-bendingly reeled back into itself and speeled through the drives head 16 times faster than a standard cassette.

Two video modes were available. Either 256×256 with 8 colours, or 512×256 with the 4 colours of black, red, green and white, which you will see evident in most applications software. This screen mode can accommodate an impressive 25 lines of 85 characters! Whoop!

Two custom ULAs were created to handle the video, DRAM and external interfaces such as the RS-232 ports. These were the ZX8301 (which was a play on the QL’s development codename – the ZX83) and the ZX8302. The ZX8301 responsible for clock timing and the video display was initially very fragile and even unplugging the RGB connection whilst in use could fry the chip. The ZX8302 also had it’s quirks, including only 1 RS-232 receiver, meaning that both serial ports had to run at the same baud, essentially forbidding the ability to connect a printer and a modem at the same time.

An Intel 8049 chip was used to control the rather limited sound output. Unfortunately, we had to wait until 1985 and the Spectrum 128k+ for a proper sound chip to appear in a Sinclair machine.

It’s common on early machines to see a mess of fixes and re-wiring which are essential to make the hardware operate without glitches.

The back of the machine sports two proprietary local networking sockets for connecting QLs in serial (if you ever see more than 1 at a time), an RGB out connector, TV modulator out, two serial ports, two custom joystick ports and a ROM connector for cartridges and expansion devices. Mine still has this neat little black cover in place.

The case itself is very industrial and angular – a step away from the soft features of the Spectrum – featuring a new type of spongy plastic keyboard which backed onto a membrane and metal fixing plate. It’s a huge step up from the original rubber keyed Speccy and would feature on all subsequent Spectrum models to come. I actually really like the feel of this one, it feels deeper than the later Spectrum keyboards and somehow more responsive.

Power is supplied through a 9v DC brick, similar to other Sinclair machines, but with a new 3 pin adaptor going into the machine.

On boot of the machine, you’re first asked whether you’re using a monitor or TV display. With SuperBASIC offering a multi window experience for monitors. Upon selection you’re then booted into a command line which serves as both the operating system and BASIC interpreter. GST Computer Systems were originally commissioned to write the operating system, but Sinclair instead opted for the multi-tasking in-house QDOS produced by Tony Tebby, which resided in the 48k ROM. GST’s offering was later made available via a ROM cartridge and the object format inspired by them would later be used to create programs for the Atari ST, including 1stWord, the ST’s bundled Word processor.

The built in programming language, SuperBASIC is, command wise, much like the standard Spectrum basic, although there are no keyboard shortcuts and you have the addition of structure! This means that line numbering is essentially done away with, in place of labels and repetition features, much like Quick BASIC for Microsoft DOS. It’s actually the first second generation BASIC language of this type to be built into ROM.

Flicking through the massively hefty & apparently photocopied manual – printed before the machine was even made – you can see, like the machine, it was clearly rushed, evident from the number of corrections someone (possibly Clive himself) has made in this copy. But, inside, you’ll find some BASIC programmes to type in and show off to your fellow professional work colleagues.

Ooooo.

Ahhhh.

Mmmmmmmmm.

Ahhhhh, the good ol’ days of BASIC interpreters on boot.

Software

This would ordinarily be the part where I talk about games, but as the QL was intended for more serious use. I’ll cover some of the applications software first. Now, my machine comes with this delightful Microsoft Office like box of applications developed by PSION, of handheld organiser fame. *Oooohhhhh, which one to pick*. Inside there’s the choice of Quill, a wordprocessor, Abacus, the spreadsheet, Archive which is a database and Easel which offers business graphics and charts. To load each micro tape up you simply use skill and finesse to un-case it, ahhhh, errrrrm, yep, OK! Then…. plonk it in the first Microdrive for loading. A swift boot and the drive whirs into action delivering you into your choice of application. The software is surprisingly easy to use, and although they don’t have the same commands as Excel or Lotus 1-2-3, they do the job you’d expect for business software. I wouldn’t be too trusting about saving my work to those Micro wafers though. Hmmmmmmmmm.

Thankfully there are a number of games available for the system, and better yet, the dreaded (but quaint) colour clash from the Spectrum is gone. Instead we’re offered what appear to be more colourful visuals, but on second inspection expose themselves as limited to 8 colours on-screen from a palette of 256, albeit with the ability to flash each pixel. This limitation stifles the games somewhat although clever overlaying can produce more colourful visuals.

Anyway, here’s the best of the bunch.

Demise

Despite not achieving it’s expected sales, the QL did make some progress into professional and home markets, selling 150,000 units. Enough for several companies to pop up and support users who had plunged into the machine. However, it was no where near enough to save Sinclair’s fortunes, having already failed with the Sinclair C5 and suffering the video game crash of ’85. Out of this innovative misfortune, Alan Sugar’s Amstrad stepped up, and using purely capitalist driven skills, acquired Sinclair in early 1986, immediately abandoning the QL. Fortunately the same companies who supported the machine beforehand, quickly stepped up to fill the void, including CST and Dansoft, who created the Thor line of compatible machines.

The original creator of the Linux kernal, Linus Torvalds actually attributed his operating system breakthrough to having owned a Sinclair QL himself sometime around this era. Being fed up of the limited software array, he decided to write his own, and from there Linux was essentially born. He then later ported this to PC to meet a somewhat expanded audience.

Because of the machine’s expandability, new ROMs were created such as the Minerva replacement for QDOS. There were also expansion cards such as the Trump card which added memory expansion and a floppy disk interface. In the 1990s, two redesigned motherboards were created for the system, offering much more powerful CPUs and additions such as ethernet and the actual ability to run the Linux operating system, and in fact, some hardware and software is still created for the machine to this day. Pop onto some QL forums and you can see that there’s still at least some people who are making use of what this machine had to offer. This includes a swave of emulators on various platforms and even an official successor to QDOS called SMSQ/E, again written by Tony Tebby.

Maybe, like the Sinclair C5, Clive was just ahead of his time with this often forgotten machine.

Surprisingly, given the reliability issues with a lot of Sinclair hardware, most QLs seem to be in good working order today, although Microdrive’s and their software are more hit and miss. If you’re lucky enough have a system with Samsung made microdrives, you still need to be wary of eroding felt pads on the wafers themselves. But hey, most of my software seemed to work just fine. So if you’ve got a spare £80 odd quid, why not pick up a genuine piece of UK computing history and give it a bash. What’s the worst that can happen?

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.

6 Comments

Add Yours →Hi mate

Really enjoyed the video. I am not Alan Sugar’s biggest fan by any stretch of the imagination and while his arrogance and bully-boy tactics have almost vilified him regarding Sinclair’s story (especially the way he is portrayed briefly in “Micro Men”) you have to admit that Sinclair had the genius and Sugar had the business sense. Sinclair felt he could tell people what they wanted at times much to his own detriment but Sugar could sense what they wanted and what they would ultimately spend cash on at least until his own company went under. In terms of the QL if it wasn’t selling then why keep it going like Sinclair did with a few projects.

Being Welsh and having worked and lived near Port Talbot I am looking forward to you touching on the Dragon 32 in the future.

[…] QL (Wikipedia) Sinclair QL (Old Computers) Sinclair QL (Nostalgia Nerd) ZX Microdrive […]

Nice write up and review.

I did notice one error. In the Hardware section you say “but only an 8 bit address bus“. I think you meant to say 8 bit data bus.

Mark

I still use my QL albeit with an aftermarket 5.25″ Floppy Drive System. I also still use my TS2068, TS1500, TS1000, etc. I sort of got stuck in the past and never left. Most recently I have considered licensing the 68080 core and making a more modern QL for my own edification, however, I alone do not posses the skills to pull this off. Enjoyed this article and video very much.

what about audio please?

Unfortunately, we had to wait until 1985 and the Spectrum 128k+ for a proper sound chip to appear in a Sinclair machine.

technically fuller cheetah dk tronics and a host of others offered the ay8912 sound chip in an interface for 48k spectrums I think could u elaborate on the ql audio capabilities please?