16th Century Italy was a dangerous place, and although Michelangelo lived a long life, he would witnessed some horror in his time, horror which continues to be prevalent in society. The darkness never really goes away, it just adapts to different forms, and from the latter part of the 20th century, this included digital. Now, you wouldn’t expect the life of a renaissance artist to really effect the functionality of computers some 500 years after his death, but in the March of 1992, that’s exactly what happened, and it caused one of the biggest global panics the world of computing has ever seen.

Viruses weren’t new in the 90s, they’d pretty much been around since the dawn of computing, but with bulletin boards becoming ever more popular in the 80s, they started to jump from computer to computer quicker than ever before. Traditionally, however, most viruses would rely on physical media as their mode of transport. An infected file or boot sector could jump from a floppy disk to a hard drive, or simply to memory and onto another disk. If that disk was then inserted into another computer, that machine would become infected and so on. It’s not quite as efficient as the internet, but you’d be surprised how quickly these things propagated, and that was really the problem with the Michelangelo Virus.

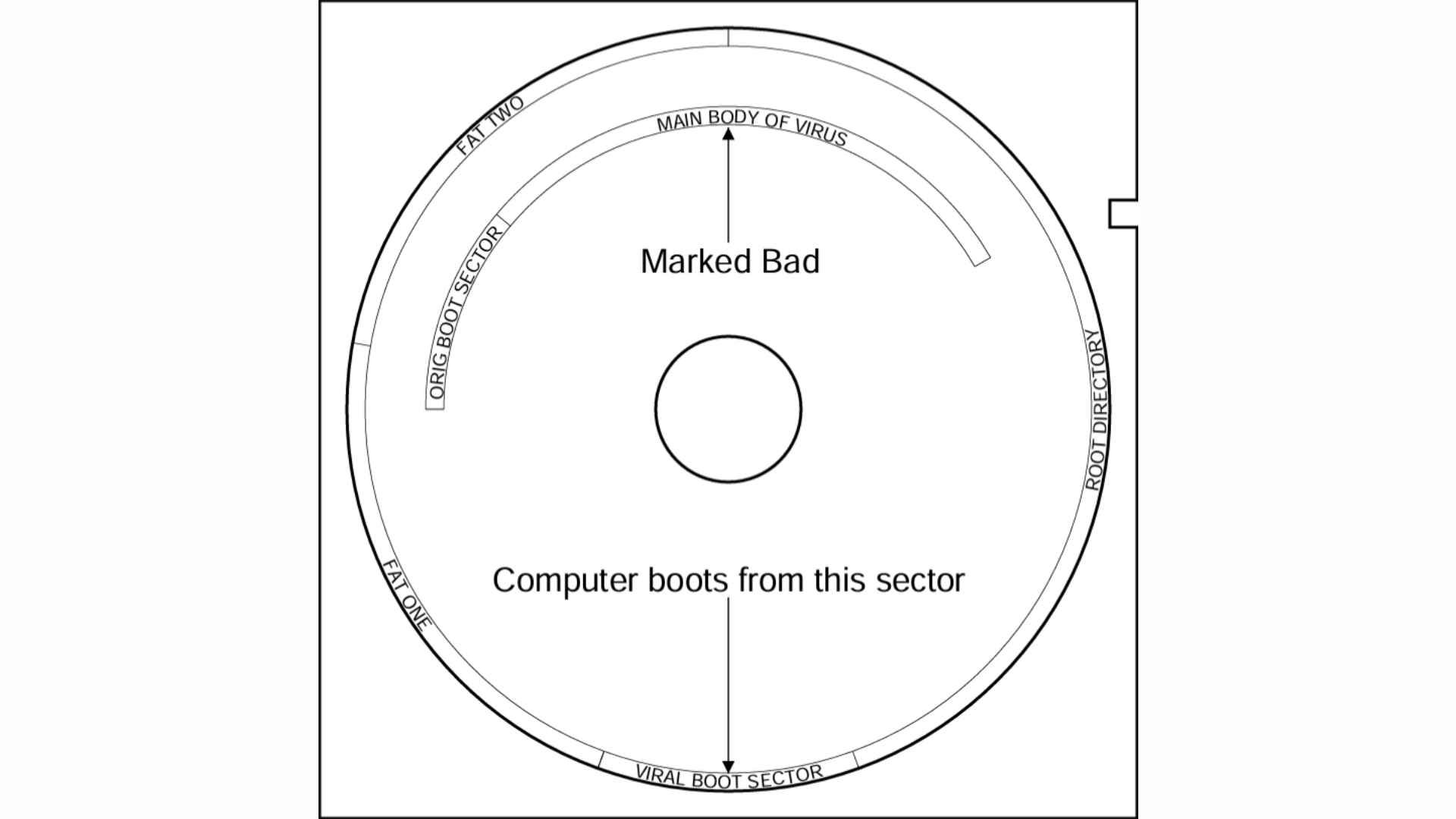

The Michelangelo virus was first discovered in February 1991 by Roger Riordan; an Australian anti-virus expert. Riordan realised that this new, then unnamed, virus was a variant of the Stoned Virus; a fairly passive little piece of code that utilised the randomness of your system clock to throw up the message “Your PC is now Stoned!” approximately 1 in every 8 boots. However, with this new virus, there was no message, no warning, it just did it’s thing and disappeared into the night. Unfortunately its thing was a lot more nasty than Stoned.

During a virus meetup in the Netherlands during April 1991, a date the media often touted as its discovery date, it was discussed by the community and identified as a possible strong future threat. Its payload was designed to activate on March 6th every year, Michelangelo’s birthday, the reason why Roger Riordan would name it the Michelangelo Virus. Of course, 1991’s March 6th had been and gone, but the virus by then, hadn’t had much chance to propagate, and therefore very minimal damage was done. However March 6th 1992, what would have been Michelangelo’s 517th birthday, could be a different matter. By October of ’91, most new anti-virus software of the time was able to detect and remove the virus, but back then, software didn’t automatically update, and most people weren’t even aware they should be using Anti-Virus. However with computers becoming ever more popular, disk sharing and file copying was rife, making for the ideal circumstances to spread chaos.

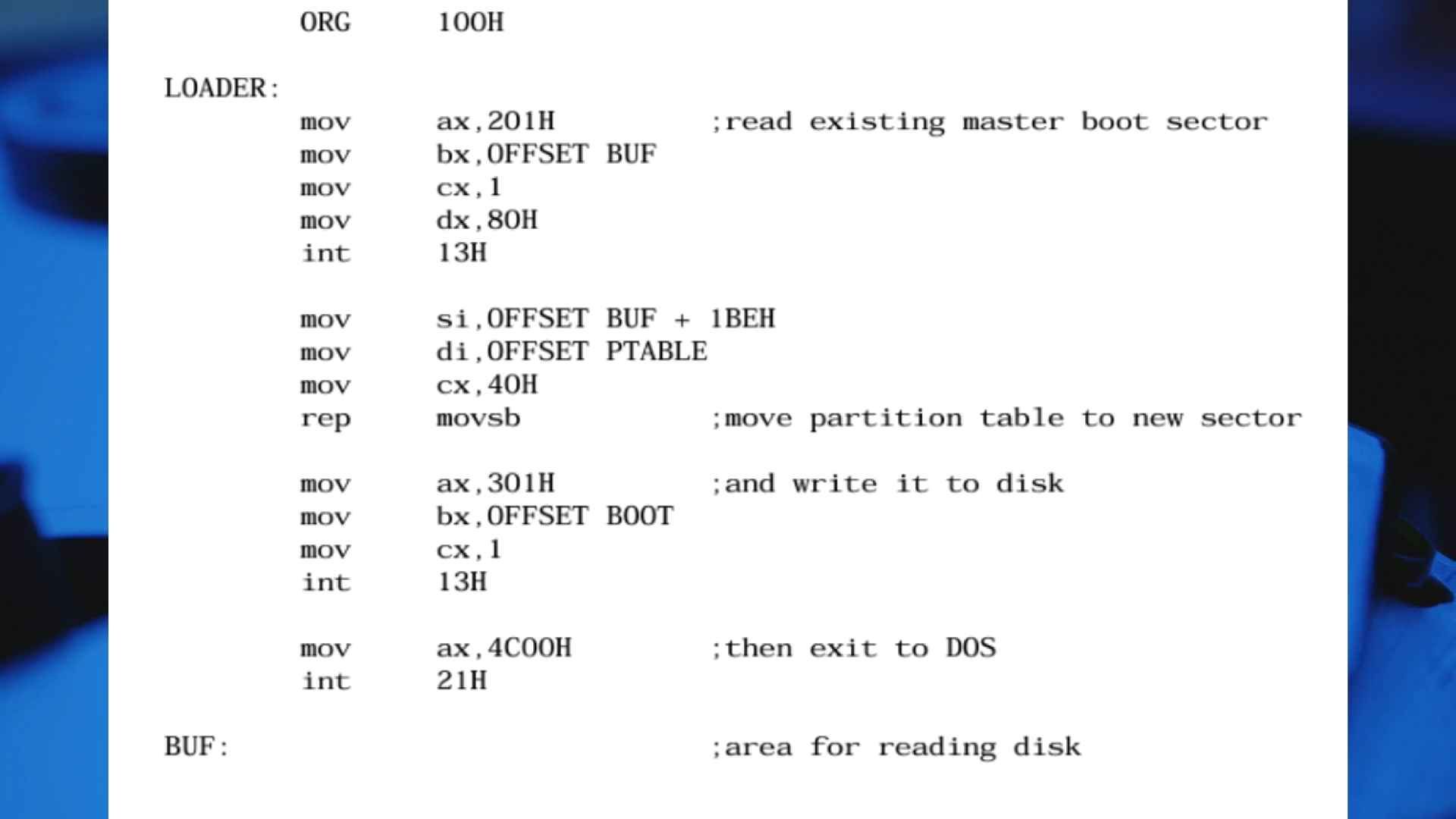

Now just like Stoned, and in fact, the real Michelangelo, who apparently slept in his boots, Michelangelo is a bootsector virus. This means that it doesn’t actually execute from within the operating system, which would have been DOS at the time. Instead it executes at BIOS level on AT based IBM PC Compatibles.

When you turn your computer on, there’s a small period of time where the BIOS is actually in charge of proceedings. The BIOS is really the gateway to your computer’s hardware, but at some point, it passes control over to operating system, and it does that by going to the first sector of your hard-drive, or floppy disk if one is inserted, and running whatever it finds.

If you were to boot from a floppy disk with an infected boot sector, Michelangelo would first load straight into the top of system memory, reallocating interrupt 12 so it didn’t get overwritten, before inserting itself into the bootsector of your hard drive, and shifting the original boot code to cylinder 0, head 1, sector 14. From that point, every new floppy that is accessed on the computer will be detected by Michelangelo and also have its bootsector rewritten. In this way, a single machine can very quickly infect a lot of disks. If any of those disks are then booted on another computer, the cycle continues.

For most of the year, this bootsector shuffle would cause absolutely no problems, however, if you computer was turned on on Michelangelo’s birthday, and your computer clock was set correctly, then as Danoct1’s channel demonstrates, this would be your fate.

Once activated Michelangelo simply overwrites the first hundred sectors of your hard drive with nulls. In doing this, the DOS Boot sector and File Allocation Table are destroyed, the latter acting as a lookup table for the data stored on your disk. So although the actual data is still there, there is no longer anyway to tell when one file ends and another starts, making recovery for the typical user, almost impossible.

So once activated, it’s a very destructive virus indeed, and if there were reasons to think that it could have spread to a lot of computers, then the panic in the air, would, as you expect, be palpable.

and they had good reasons to feel like this…

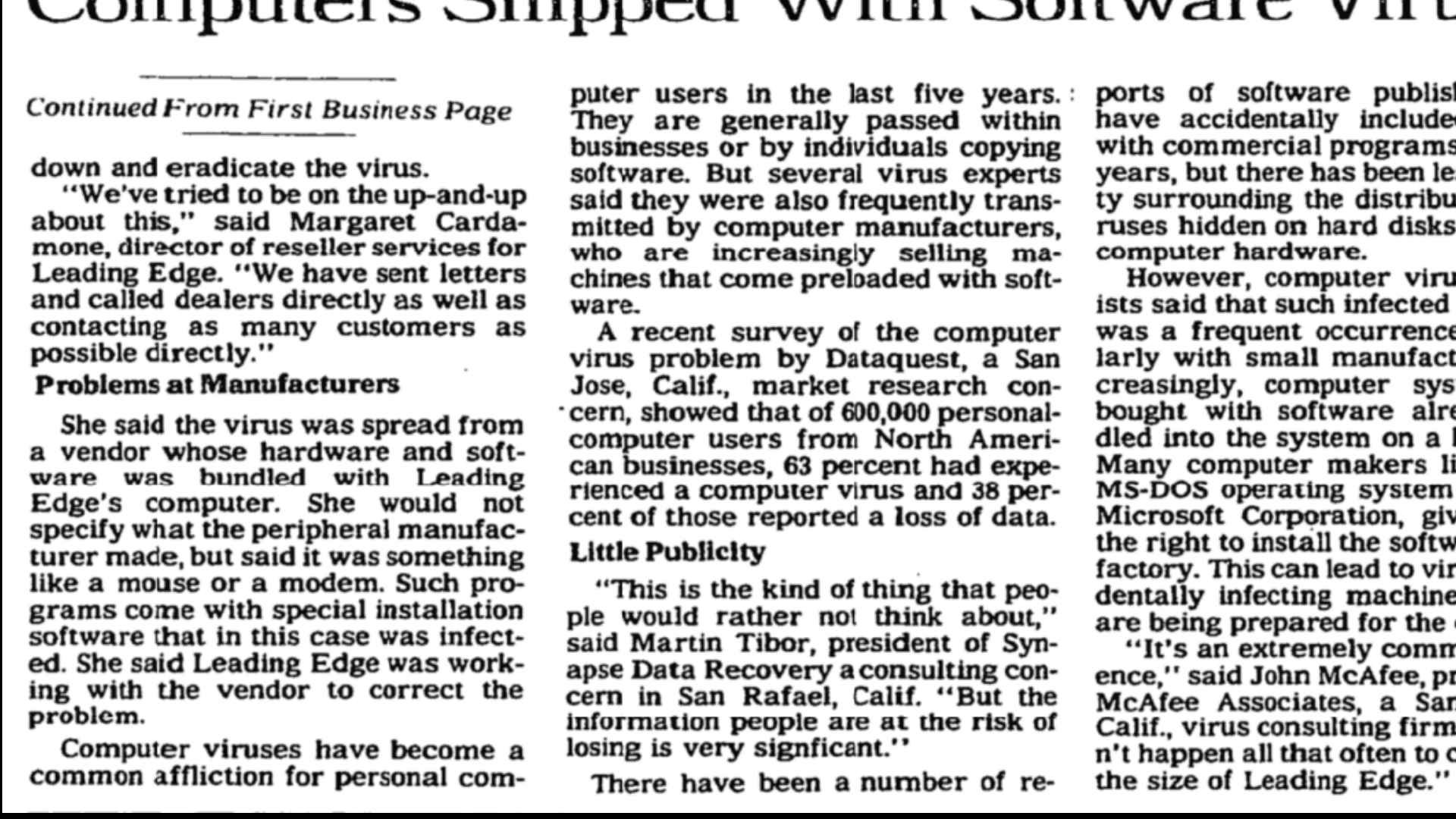

The Virus Commeth

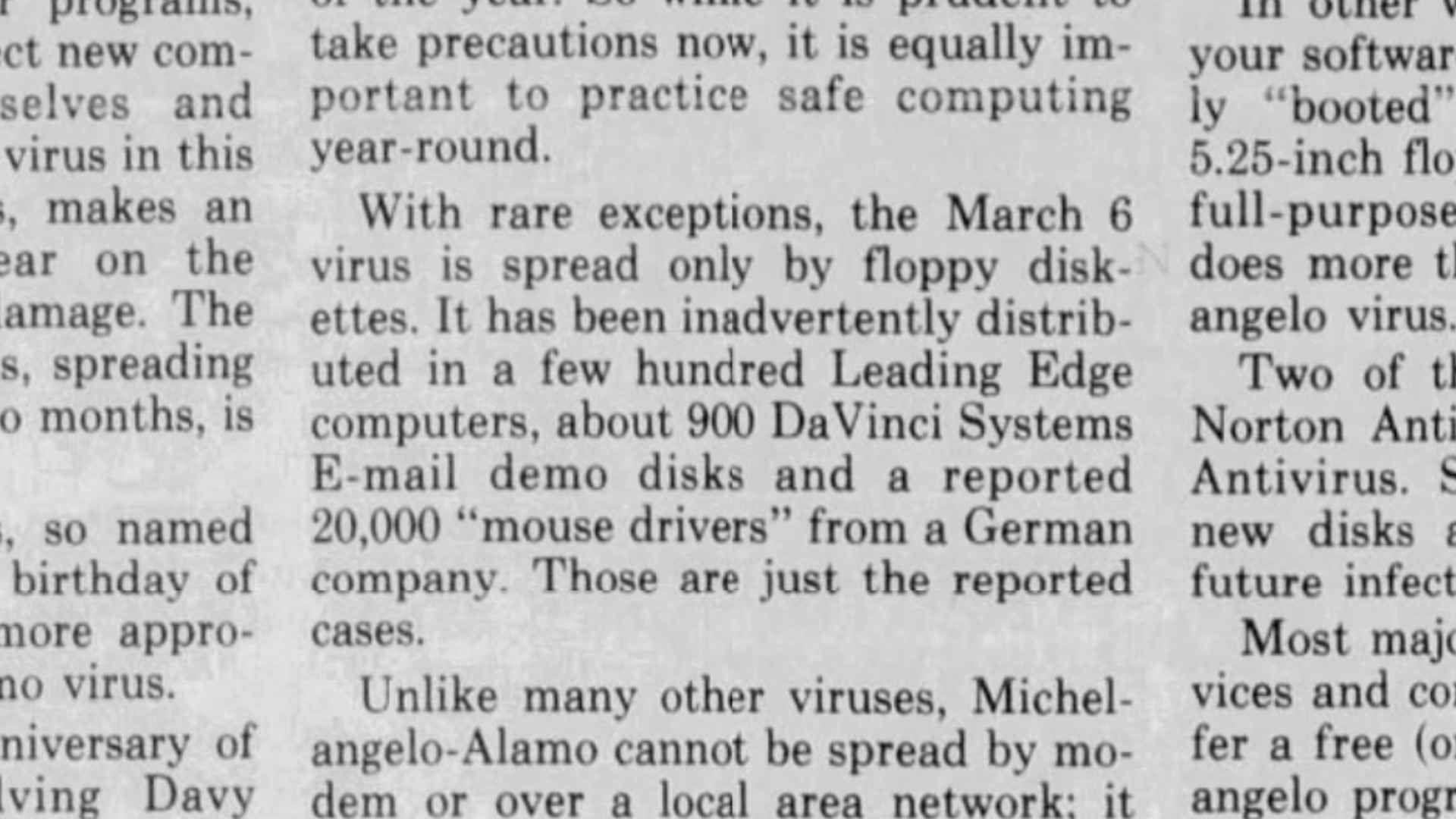

On 28th January 1991 various news outlets reported that American computer manufacturer Leading Edge had shipped up to 500 computers between December 10th and 27th infected with the Michelangelo virus. Warning of it’s dangers, Leading Edge had stated they planned to send customers special software designed to track down and eradicate the virus. Apparently the virus had spread from the driver disk of a modem vendor. The New York Times had also contacted John McAfee, president of McAfee Associates, who stated “It’s an extremely common occurrence. It just doesn’t happen all that often to companies the size of Leading Edge”, in what certainly would not be the last words we hear from him. In a fantastic move of foresight, Osicom Technologies also announced it would bundle an antivirus package with all personal computers on the same day.

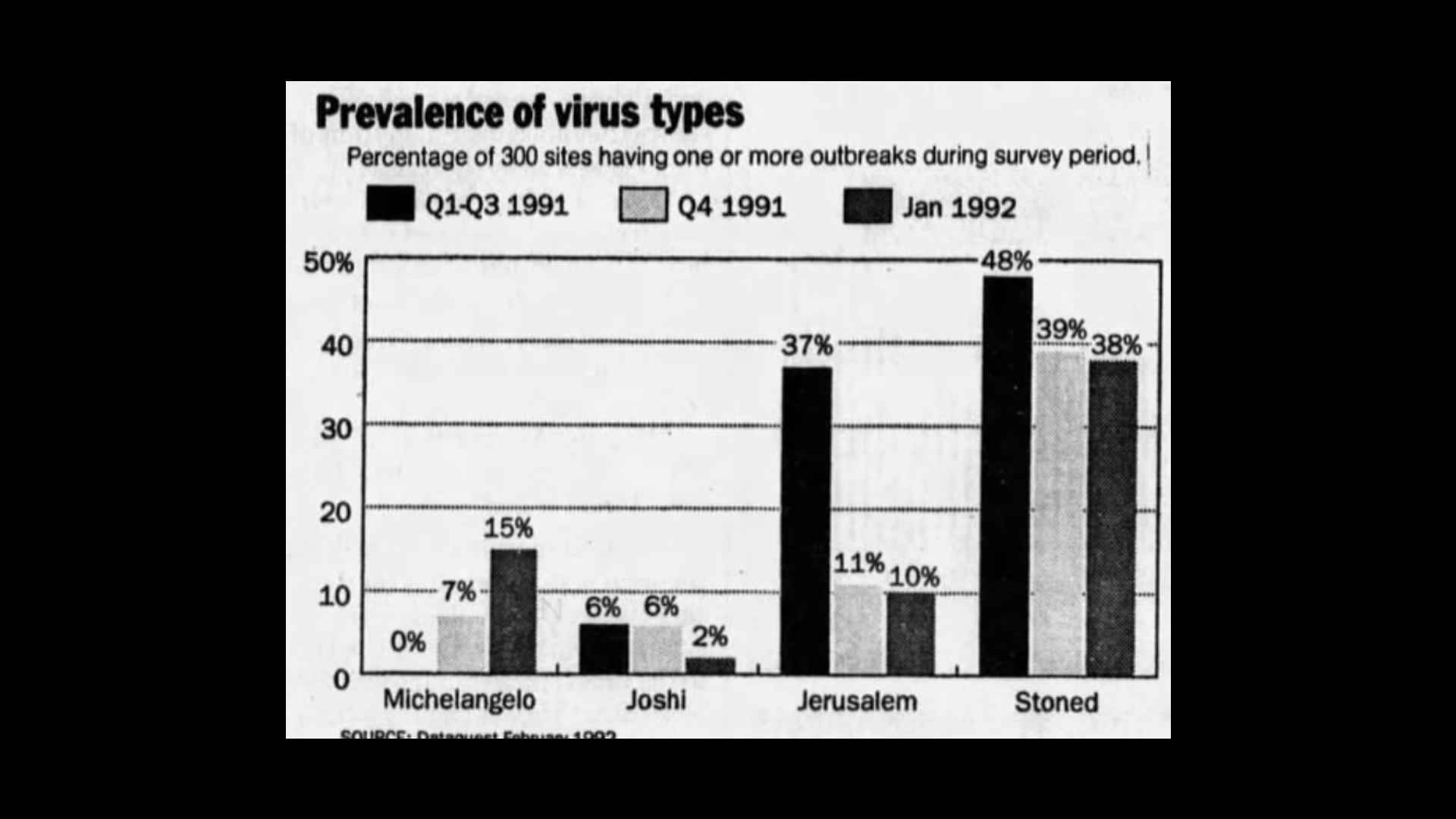

The next day United Press reporter Jack Lesar stated that “Michelangelo could erase data of hundreds of thousands of computers around the world”, whilst Winn Schwartau, director of the International Partnership Against Computer Terrorism stated “usually a virus can’t be propagated by just reading a data disk. But it appears to no longer be true”, making Michelangelo seem like some kind of magical nefarious being. McAfee also piped up again stating “The Michelangelo Virus is the third most common in terms of reports of infection. It accounts for 14 percent of infection reports – a total of about 6,000 last year, each which may be one machine or 100”.

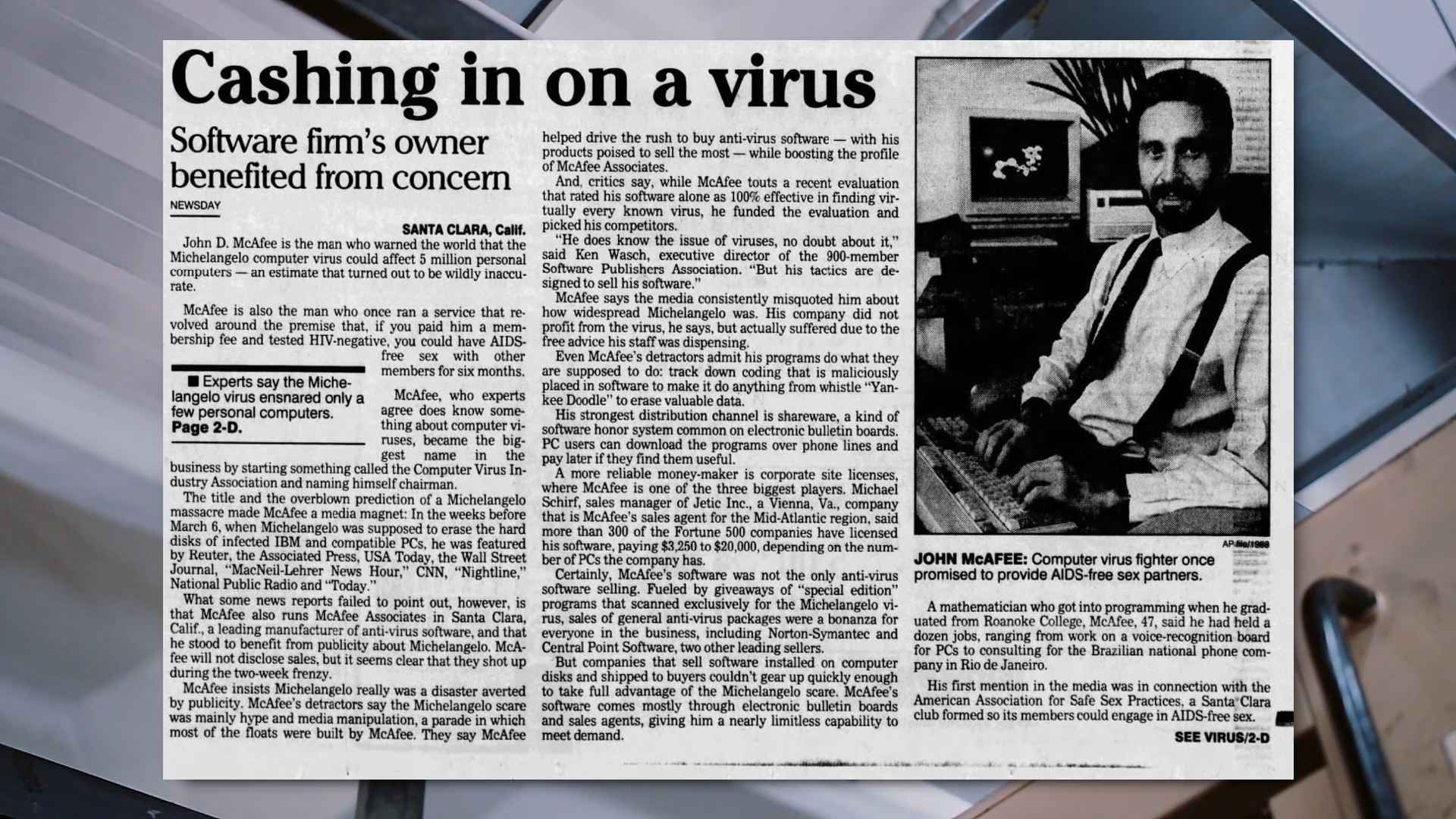

As February rolled around, things only got worse. On the 3rd, it was reported that Da Vinci systems had distributed 900 infected disks during January and by the 11th McAfee was back again, this time stating that 5 million computer around the world were infected. Something that Reuters reporter Wilson da Silva would relay to the masses.

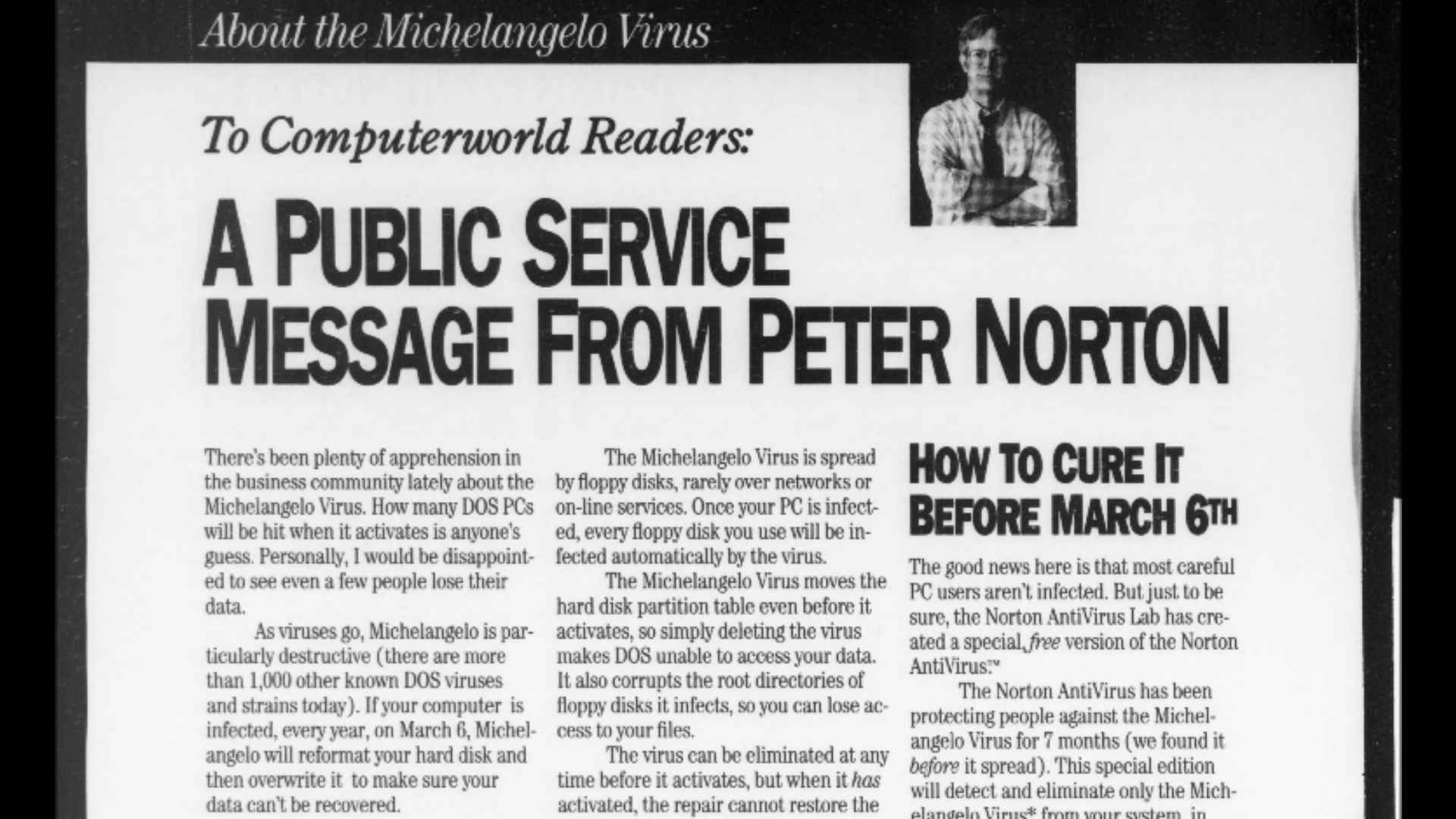

By the 13th, the rest of the Anti-Virus world, was getting a little jealous of McAfee’s spotlight and decided to do something about it. Microcom announced a free problem to disinfect the virus, and by the 19th Symantec had announced their free program, which they advertised to the readers of Computerworld in a full page spread. Users could download a copy via Compuserve, go to a local dealer, get one delivered or use a Bulletin Board System. The only problem with the latter was that lots of the media were now incorrectly suggesting that Michelangelo was spread through Bullet Boards. Gotta love the media. Reporting news accurately since, well, since the dawn of time.

By the end of February, the hype was insane. Various “Anti-Virus” experts had piped up, along with computer columnists such as Lawrence Magid who suggested leaving your computer on from the 5th of March to the 7th in order to evade the pesky virus. All good Lawrence, unless you have a power cut on the 6th, and your computer automatically reboots.

On the 28th Seattle Based Egghead Software had offered to ship a copy of the Norton AntiVirus Michelangelo Edition for just $4.99, unfortunately, they wouldn’t actually ship most copies until after the 6th March, rendering it, a little bit useless.

March…

As Judgement day loomed, McAfee was back, this time on the today show, repeating his claim that 5 million systems are now infected globally. He doesn’t even use the word estimate. Apparently, now, this is a cold hard fact. It sends the media into further meltdown, as broadcasters and publishers rush to get last minute stories out, warning people of the global pandemic threatening life as we know it.

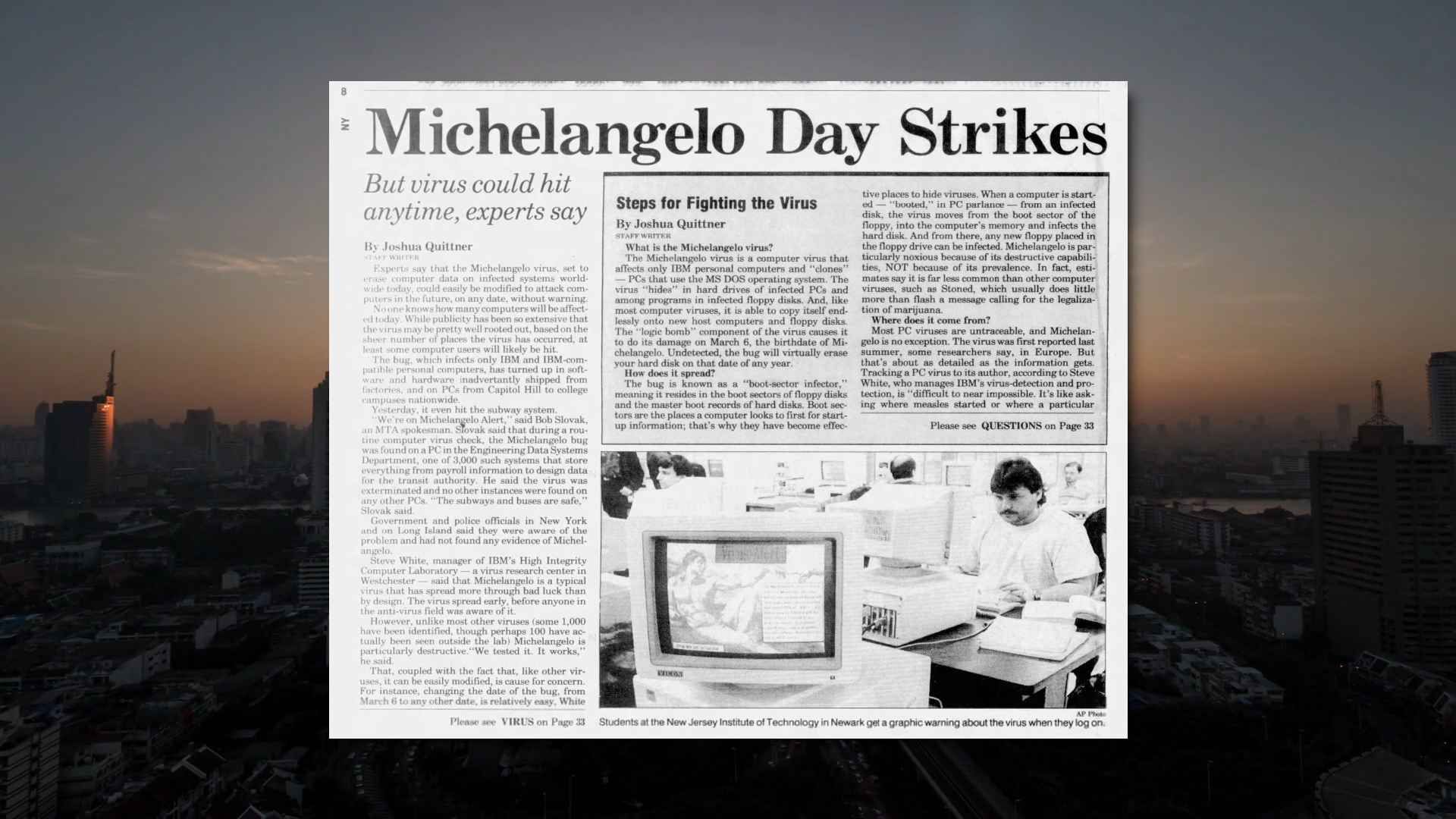

On March 3rd, Poland woke up to the headline “Michelangelo, The Mass Murderer, Will Attack on Friday”. Back in the States, not only had the Associated Press reported the Michelangelo had invaded Capitol Hill, but even Intel had problems, having to cease shipment of their LANSpool networking program, after discovering 839 disks infected with Michelangelo. They had been using anti-virus software, but it failed to detect the Stoned variant.

If Intel were having problems, then that didn’t bode well for the rest of us.

4th March: Ross Greenberg, the programmer behind Microcom’s Virex-PC Package disappears for four days. He won’t return until after the 6th.

5th March: Scattered reports from around the globe indicate Michelangelo had triggered a day early in some computers, who internal clocks failed to detect the leap year this February.

McAfee and Charles Rutstein argue on the News Hour Show about reports of how many will suffer.

V-Day Arrives. *panic* *confusion* *screaming*

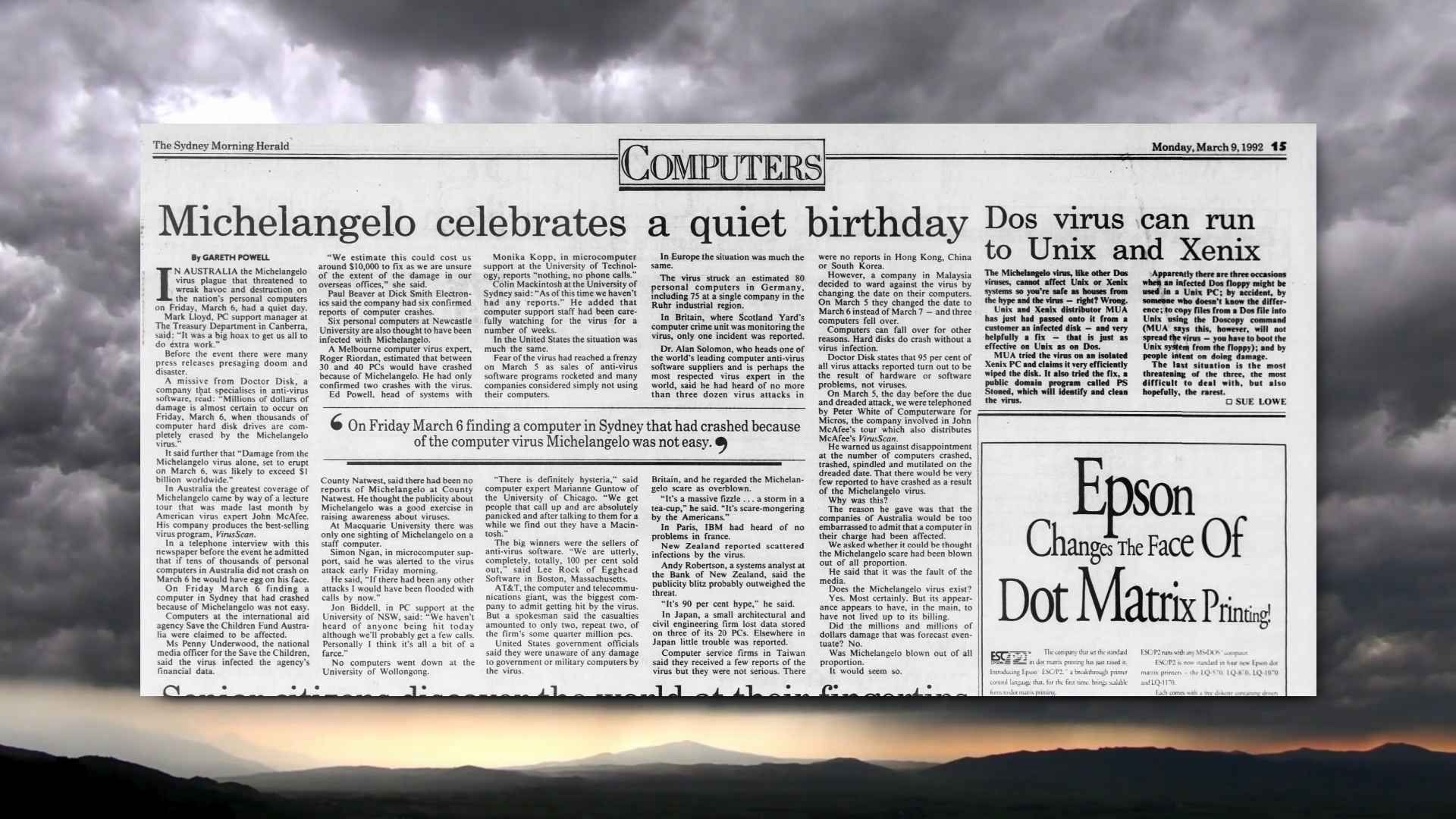

As dawn broke on 6th March, the first news stories started rolling in. Most of them were just talking about the virus, what was expected to happen, etc. An acknowledgement of the day more than anything, after all, how can you have a printed article about events which are currently taking place. This wasn’t the internet.

but what we did have, even then, were timezones, with places like Asia and Australia able to report back just in time for Western media.

AP: “Personal computer users reported scattered outbreaks today of the Michelangelo virus, but no widespread damage from the much-hyped software invader”

UPI: “The long awaited Michelangelo virus struck around the world Friday, though it did not appear to be the data disaster that some had predicted”

These weren’t the frenzied, chaos laden headlines we were expecting. These sounded more like sedate weather reports than the dawn of a global pandemic. But maybe things would be different in the States, in Europe, maybe the virus had taken a stronger foothold in these technological havens.

At around midday, 1,200 automated teller machines in New York shut down. Shortly afterwards 3/4s of New Jersey’s lottery machines went offline. The New York Hilton’s systems went down, and Philadelphia cable TV subscribers found their sets locked to the channel they had been watching the prior day. Maybe Michelangelo really had taken hold here. Maybe sh*t was about to get real.

It turned out that CitiBank had suffered a power outrage affecting cash machines, a computer glitch had affected the lottery systems, a power lead had been knocked out at Hilton and cable TV was, well being cable TV. Although residents were quick to blame the virus, these turned out to be unrelated incidents, with the day rolling on with not so much as a harsh word being uttered.

AP Reporter Bart Ziegler would send a newswire to the effect of;

“The day of techno-doom turned out to be a dud… For days, news media relayed forecasts of impending doom from Michelangelo. The story had all the right elements: a mysterious invader with a sexy name that could cause havoc by a definite deadline in machines relied upon by millions. The reports often failed to mention that many projections of potential damage were provided by companies that make anti-viral software and stood to benefit from the scare.

“One source was John McAfee of McAfee Associates, the largest seller of virus-killing programs. McAfee was widely quoted as saying Michelangelo had infected up to 5 million computers worldwide. Asked Friday whether he had overstated the case, he said the low rate of actual Michelangelo damage was due partly to precautions so many PC users took.”

AP Reporter Bart Ziegler

Based on reports to his company, McAfee himself rapidly changed his estimate from 5 million to 10,000 computers worldwide, and sure, just like Y2K, some of the damage would have indeed been limited by the hyperbole and people taking anti-virus precautions, but .2% of the original estimate is quite a drop.

Symantec claimed that a quarter of a million users around the world had obtained a copy of their disinfector program, clearly helping to deaden the impact. But the actual shouts of infection were pretty limited. AT&T reported that two of their company computers had gone down, out of their quarter of a million machines worldwide. A bowling centre in Swanton lost their bowling league information, and Rev. Stan Wilkins of the New Salem Baptist Church lost his congregation records.

Further reports the following day would indicate that damage was a little more widespread, 750 computers in South Africa, responsible for managing the country’s pharmacies succumbed to the villainy. Scotland Yard reported that two British companies suffered considerable losses and three computers at Boston University were DOA.

What didn’t happen was 5 million machines needing a full reinstall.

Harold Highland, editor in chief of the industry journal Computers and Security stated “We raised the level, the awareness, but we’ve done a great deal of harm. When thi sis all over top management is going to feel that they wasted a lot of money”

McAfee would chime in with “The biggest loser in this whole thing is going to be the anti-virus community”. Which given the amount of sales they made from this escapade didn’t really seem to be a problem, and really, was nonsense anyway.

and Scotland Yard Reported that two British companies suffered considerable losses, and three computers at Boston University were dead upon boot.

Although the entire Anti-Virus world received some backlash, with some even claiming that anti-virus companies were to blame for planting the destructive code in the first place, it was McAfee who took the brunt of it, with countless newspapers jumping on his 5 million computer claim; a claim that McAfee himself refuted, noting that he had estimated between 50,000 and 5 million machines, with the media running with the upper limit. Perhaps the real problem here was actually the hypocritical media for being so damn sensationalist, in a bid to sell more of their own product; newspapers.

Or maybe, like most things, it’s a bit of both. Always both.

McAfee would resign from the National Computer Association the first business day after the Michelangelo media fiasco, concentrating on selling more and more McAfee product. His company would go public in October 1992, raising $42 million in its initial public stock offering, and of course, remains with us today, even if McAfee himself doesn’t, having allegedly been found hanged whilst inside a Spanish prison cell, just hours after a court ordered his extradition to the United States on tax charges.

Funnily enough Michelangelo is also still with us, with detections still happening in the wild. It appears that a few floppy disks are still very much infected and attempting to do their thang.

The main lesson the media learnt was that they should probably speak to experts instead of anti-virus salesmen when trying to gather facts and foresights. However, given a similar scaremongering tale had happened only a few years prior with the Datacrime II virus, which also wiped out hard drives on Friday 13th, although not very many at all, it seems like lessons take a few attempts before they’re learnt.

It’s no wonder that the next Friday 13th Virus, which funnily enough was due just a week after Michelangelo, went pretty much unmentioned by the embarrassed media.

Roll on Millennium Bug.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.