Welcome to my local storage company. Behind each of these doors, I presume are goods, stock, furniture, personal items, junk. But I don’t actually know. I haven’t checked out each and every one. You might presume that this door leads to a palace of my retro treasures, but perhaps it doesn’t. Maybe it leads here.

Perhaps that door was a portal to a new place. A new beginning. Which makes my storage depot a transitional space. From the moment I walked in the front doors, I was leaving behind something. I could have spent hours in the transitional space, wondering where to go, but I picked this door, and I ended up here.

It’s a concept used often in films. Who can forget the keymaker in the Matrix, and the disconnected back corridors he roams. Unconnected from time, from space. But with the ability to go somewhere new. Somewhere unknown.

The concept of the Backrooms creepypasta is in a similar vein. A place you clip into, when leaving reality; A disconnected area that feels familiar and seemingly incites deja-vu. But how and where you go from there is unknowable.

Of course, in reality, my door actually does just lead to a cupboard full of future retro projects. Please don’t hire storage thinking you can use it as a portal.

But that’s not the only definition of what makes this space feel oddly liminal. More often than not, rather than a literal transition, a liminal space gives a niggling familiar feeling of transition. Perhaps a distant hazy memory, a place that you feel you recognise but can’t quite define.

The absence of people.

The absence of features or individual character.

The buzzing of an incandescent bulb.

These all add to the feeling of the surreal feeling of a transitional space. Their synthetic-ness stands out. It may be tied to a nostalgia you can’t quite place; but a cold disconnected nostalgia, rather than warm fuzzy memory; Maybe you woke up from a hazy dream in the back of a car, and recall seeing a petrol station on a journey. Maybe it was a school corridor, at a new school, the start of a new chapter of your life. Maybe a doctor’s waiting room, alien, yet familiar. Perhaps that’s why these places often feel lonely. This is your experience. An isolated inner experience.

We could get Meta and suggest this is the source we return to between lives. Maybe it’s a representation of that, or maybe traverse through spaces like this so often, they all feel familiar, like a dream.

Maybe it was a dream. After all dreams are often less detailed than real life. You might see some objects in a vague roomed context, but it’s hard to make out, hard to define and hard to remember. Dreams are also often devoid of control, which is perhaps why liminal spaces have a floaty, uncomfortable feeling. You’re just a visitor. The liminal space is happening through you, not to you.

Islands: Non-Places by Carl Burton is a game like experience that captures this well.

It’s hard to define what makes a space liminal. Whatever the connection. These visceral pangs of disconnected anxiety; these are the hallmarks of a liminal space, and it’s why places that lack features, that lack natural elements, feel liminal.

Interestingly, it’s for exactly these reasons that many old games, have the same kind of visceral feeling;

Poorly implemented controls and a single inevitable, but yet, unknowable outcome, amalgamated with low resolutions, plain textures, false colours, low fidelity sounds and basic in game characters who have a very real disconnect from other players and the real world. Everything is an impersonation. But it still offers a model of reality that we recognise.

And then there’s the undeniable feeling that for many of us, playing these early games, actually felt like a transition. We felt like it was a huge part of our life, that was changing the very fabric of what it meant to be alive… and often, it really was.

Pacman (1980)

Now, the world of Pacman might not feel conventionally like a liminal space. The world is unfamiliar from a real life perspective. But in it’s abstract form, it conjures a feeling. A feeling that perhaps made it so famous in the first place.

You begin in a maze. The walls are narrow, and there’s mess everywhere. But yet you move. You move continuously, collecting this mess. You don’t know why. You don’t know to what end. But you collect. Leaving the screen edge, simply returns you to the opposite edge. You can’t escape. The world is claustrophobic, and worse, you’re continually chased by four foes, intent on causing you harm. Your only respite is a drug, that allows you to become the dominant force for a brief few seconds. Then you’re back to collecting. Level after level. Confined. Trapped.

That feeling, that confined feeling. The world folding back on itself. The paranoia of being chased. These are the liminal elements. You’re transitioning somewhere, surely? You have to be. What’s out there in the bleakness? Why can’t we get to it. This can’t be life. But it turns out your only real transition is to corruption or power off.

Driller (1987)

The first game I experienced that really wrapped me in liminality was Driller on the Commodore 64. You find yourself in the far future, in a vessel, on a planet. A planet that is humanity’s only hope of salvation, and you have to get it ready.

This bleak image of distance, of loneliness, is only compounded by the abstract, undetailed spaces which you slowly move around. You can make out doors, towers, shelters even. Some of these places feel familiar in their construction. But what are they there for. What can you do?

Well drill, that’s what you’re there for. But for most of us, just diving into this game to experience a true First Person Perspective. It was a new world we were swept into, and instructions were superfluous to this feeling of being somewhere new, yet familiar.

Hard Drivin’ (1989)

In a similar vein, Hard Drivin’ seemed to do the miraculous thing of making you feel free, yet utterly confined. Trying to navigate the short, looping tracks, with twitchy controls, and the odd ominous landmark, felt comparable to being in a car; seeing building shapes late at night, but not knowing what they were. It’s a game where you have time to look at the scenery, but not for too long, with the constant threat of destruction looming.

Sometimes a faceless, bland, void of a vehicle will pass you. Sometimes it will race you. But these vehicles felt utterly lifeless. Like robots doing the rounds. Keeping you in check for a fate that you don’t quite realise.

If only there was a way out of this place. Out of this car. Maybe then you could make for freedom.

The Terminator (1991)

This is my favourite scene in the Terminator, because this nightclub is the transitional space. The moment Sarah enters, her ultimate fate is either death or the realisation of a new life, and that fate is decided by accidentally knocking over a beer.

This film captures the very essence of liminality throughout. The feeling of loneliness, of disconnection from your fellow humans. Despite them being everywhere, they’re unable to help, unable to understand.

The Terminator, as a film, manages to capture a liminal feeling throughout. The feeling of loneliness. Disconnection from your fellow humans. Transitioning to a different life, that seconds ago, you were unaware of. Even in a packed nightclub.

The DOS game then, manages to do the same, but in a very different way. You see, early DOS games were somewhat devoid of, well, graphical finesse, and as you drive around as Kyle Reese, you feel disconnected from reality. Those buildings, they look like buildings, are they buildings?

Well yes they are, and the street layout is fairly accurate to the included map, even down to significant landmarks.

The whole game manages to capture that eerie mood. Even when you enter shops and are confronted with more detailed scenes. This could well be a shop you visited when you were younger.

But here it is, devoid of life, in a context you’re unfamiliar with.

It may not look like The Terminator, but the spirit of The Terminator is well and truly present.

Another World (1991)

Another World gives you the gift of a name, Lester, and a job, you’re a physicist. Apparently, your life is all in order, as you arrive in your Ferrari 288 GTO, but a short lightning strike later, and your current particle accelerator experiment throws you into a completely different world, even Universe. You’ve very much transitioned to a space which feels familiar but is very different.

The trick was, we’d never seen graphics like this before. Another World, through it’s rotoscoped graphics, drenched alien atmosphere and few but carefully placed sounds and musical accompaniments actually brought us along on the journey as much as Lester.

It’s different approach to 2D platforming meant that we were experiencing something that felt like a new era, and for that we were rewarded with a disconnect from our real surroundings, and an absolute connection with a world somewhat less detailed than our own.

DeathMask (1994)

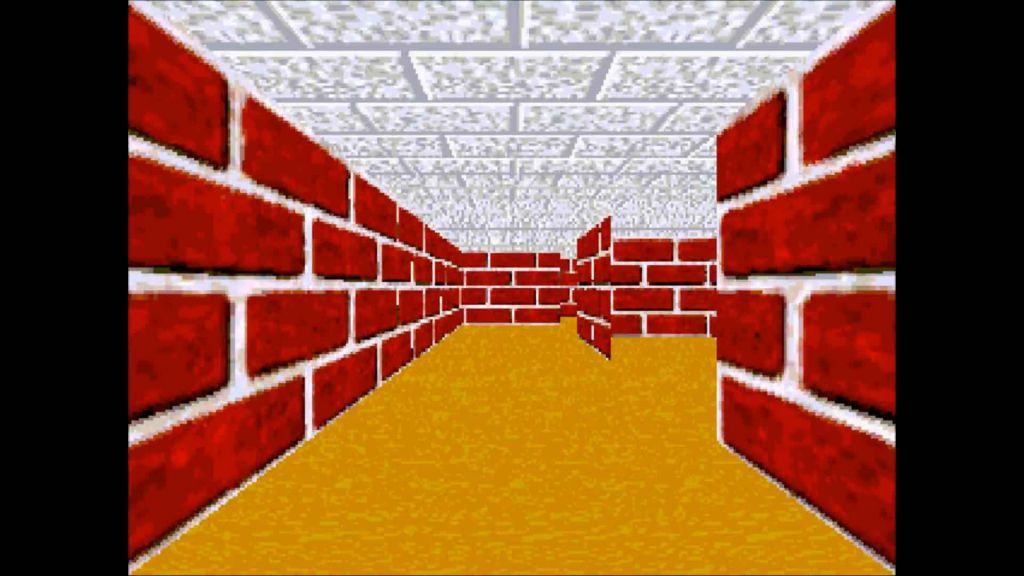

Like Another World, Death Mask feels at home on the Amiga. In fact running on a 7MHz Motorola 68000, with 1MB of RAM and 16 colours to play with definitely adds to the disconsolated feeling.

The game isn’t really 3D. It’s more like an FPS Dungeon Master, as you step slowly around corridors, passages, that could easily be from your mate Tom’s basement.

You have no idea what’s around each corner. It could just be exactly the same. Almost featureless. There could be a skull, or sometimes, you encounter an opponent. These encounters are always brief, fleeting, and honestly a bit confusing. The controls of Death Mask make the whole ordeal feel like it’s being played out in a room of starch, and that adds to the uneasy, yet familiar feeling.

You’ve surely been here before. You were struggling. Trying to get away. But all you got was another corridor.

Maybe I just had an odd childhood.

Maze (1996)

So how about a screensaver? The Windows 3D Maze. This is a process you truly have no control over. You can exit of course, with just a wiggle of the mouse, but do you want to do that? What if you miss something important around the corner, what if the next corner finally leads to freedom?

A new version created on itch.io called Screensaver Subterfuge does actually allow you to move about however. You take control in a bizarre world of international espionage, and it actually makes it feel like more of a fever dream than it ever did before.

Rugrats (1998)

The Rugrats games come up frequently when discussing liminality, and that’s because, well, the worlds you inhabit are just so bizarrely uncoupled.

From the strange devoid, child play areas from Search for Reptar in 1998 to the oddly abandoned Theme Park from Rugrats in Paris. It’s all very, ominous, and it really shouldn’t be. These are games designed to entertain children. But all they do for me, is send a deadly cold chill down my spine.

I thought being locked in a Theme Park would be a childhood dream, but it’s not. It’s filled with dream like anxiety. I feel like I’m being chased by Yul Brimmer. These places look familiar, or at least they look like a fake version of something familiar, but the lack of people, especially when you’re roaming about as a small child, is disconcerting.

Mirror’s Edge (2009)

Mirror’s Edge is another game that although isn’t devoid of life, certainly has less of it than you might expect. Controlling Faith Connors, you bundle from place to place, building to building, in a world that looks graphically pleasing, but at the same time, lacks any real detail.

Of course, most of the time, you’re too busy trying to pull off a sequence of acrobatic manoeuvres to stop and look, but if you do, then the whole place get’s very strange indeed.

The Stanley Parable (2011)

Perhaps the game which conveys Liminality best is The Stanley Parable, which is odd, because you’re almost never alone.

Throughout the game, you have a companion. The narrator. He guides you, or doesn’t guide you from place to place, trying to describe what’s unfolding, or what perhaps should unfold.

Strangely though, this narration, if anything, makes you feel more alone. Especially when it stops… and you’re left your own devices. What do you do? Where do you go?

You could spend all day just turning computers off if you wanted, or try actually working. After all, you are at work.

Or you could go back to making choices. Just like back at the Storage company, we’re here, deciding which door to choose, which ending we’ll get to… and this world is the vessel for that transition. Of course by the end of it, we start again and go through every ending. Perhaps a choice we don’t have in real life, and perhaps why the Stanley Parable is so compelling and liminal in the first place.

The Backrooms

Which brings us to the Backrooms, of which there are several namesakes. These games are all, really based around the Creepypasta, and have a solid foundation in ideas and elements of old. Of clipping out of real game worlds, or real worlds, and finding yourself here. In a place that you may, or may not be able to escape from.

In a way, it feels like clipping through walls of actual gaming experiences of old. Sometimes you’d find yourself in a whole new location you’d never seen before, and that was fun, although also a bit scary. In a way, maybe it’s playing those games in the first place that has given us recent feelings of liminality.

…..and it’s also the reason why we have games like The Stanley Parable and Baldi’s Basics. They’re built on this eerie framework of the past. Creating something familiar, but at the same time, terrifyingly unknown.

Of course, my list here is far from definitive, and in many games, you’re more than likely to find at least one liminal segment. One part which gives you that slight feeling of unconfirmed dread. But let’s be honest, it’s that feeling which keeps us coming back for more.

Do you have any experiences of liminalness in games? If so please let me know in the comments.

Until next time, I’ve been nostalgia Nerd. Toodleoo.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.