IBM. Big Blue. They were the ones who instigated, who created the very platform that most of the world uses for their desktop endeavours. It’s open architecture that helped it become a great success, was also, in the context of IBM’s business, it’s demise. The Personal System/2 then, released in 1987, was IBM’s attempt to recapture some of the market that it had lost to rivals creating compatible machines, with Compaq being the most formidable. These new machines gave us futuristic looking designs, coupled with proprietary hardware, designed to bring consumers more firmly under the IBM wing. This proved popular with business buyers, familiar with IBM’s sales rep, but penetrated less so into the home markets, with consumers opting for cheaper, and often higher specc’d competitor machines.

IBM then, needed a way to expand again, to create the same sort of personal computer growth they had witnessed in the early 80s, and one of the ways they saw this happening, was through the portable computer market.

The problem was, IBM were already making portable computers, and compared to the competition, they were abysmal. Bulky, unimaginative and late to market, weren’t really key selling points, especially for executives out and about, looking for something small and reliable to work away from the office. But there was one man who had a vision and that man was Jim Cannavino.

The book, Thinkpad, a different shade of blue by Deborah Dell and Gerry Purdy documents how Jim would eventually do the ground work for the IBM Thinkpad line; one of IBM’s long awaited success stories, but there were a few developments needed before that to pave the way;

“The world was desperate for a desktop replacement laptop. I felt that portables had a chance to provide the PC company with a sustainable foundation… I knew that it would eventually be an individual’s only personal computer… I thought there was a whole niche that would run with just portables. That has certainly turned out to be true”

Cannavino had convinced IBM to eschew their traditional 3 year development cycles, and instead run with one lasting only a year. To do this, a skunkworks team was assembled, to work separately from the main company, and IBM’s Yamato lab in Japan were brought in for design.

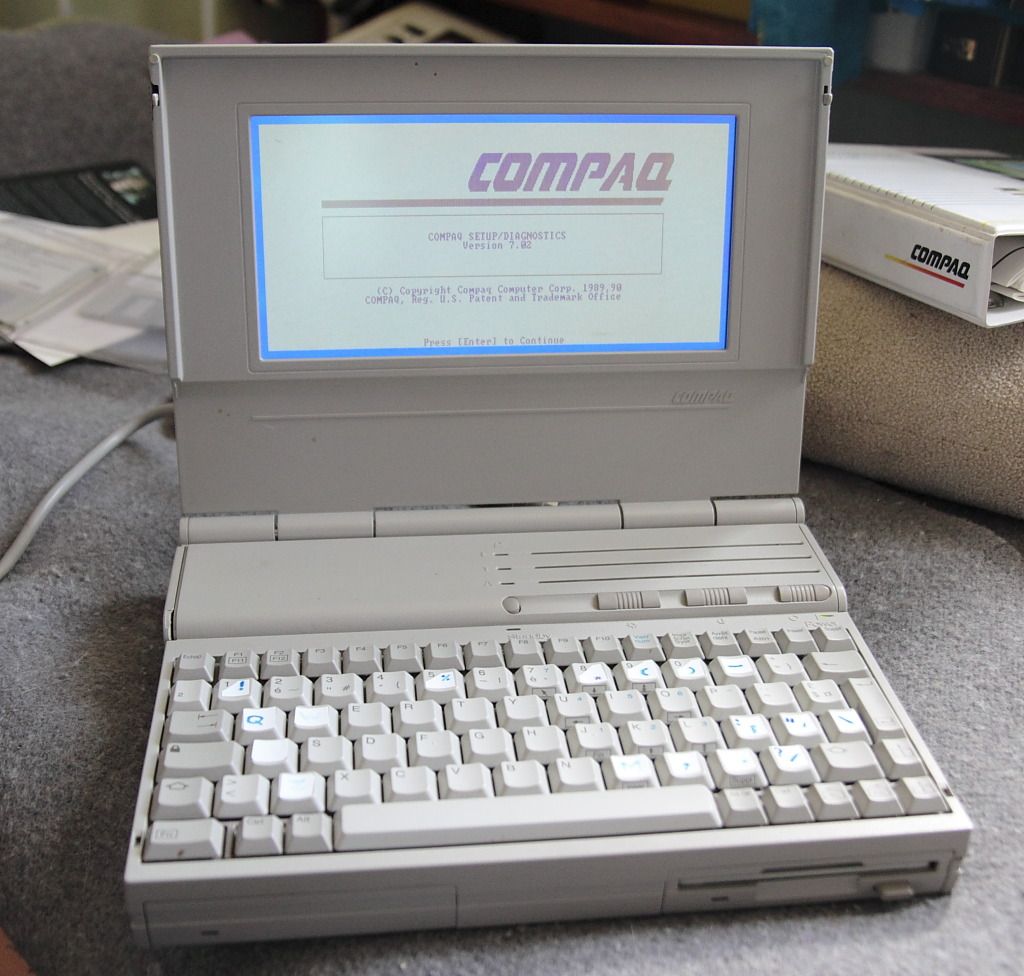

The outcome of this was the PS/2 P70. An IBM, that was in the marketplace, at the right time, and because of that became the number 2 selling luggable in the market, second only to Compaq. IBM went from a 1.4 billion dollar loss in 1988, to 1.2 billion dollar profit in 1989, with the PS/70 contributing significantly toward that. The P70 was followed by the P75, BUT, there was issue. Compaq had again delivered not just something that fitted consumers needs, but was redefining consumers needs.

In October 1989, the Compaq Lte, based around a 8086 processor and the Lte 286 were introduced. What most would consider to be, the first notebook computers. Weighing in at just 6 pounds, compared to the 22 pounds of IBM’s P75 luggable. Overnight it made IBM’s portable range seem like cumbersome desktop machines.

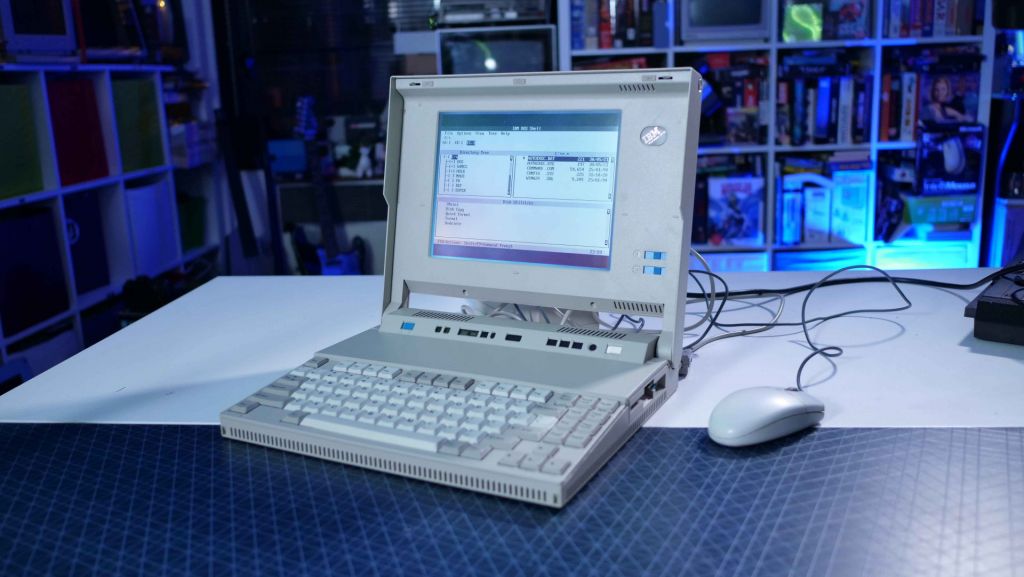

Business customers quickly began asking their IBM reps when their notebook would be coming out, and once again it was down to Cannavino to step up to the task, with Bob Lawten leading the team; the result of which was the L40SX Laptop, released in the USA on March 26th 1991.

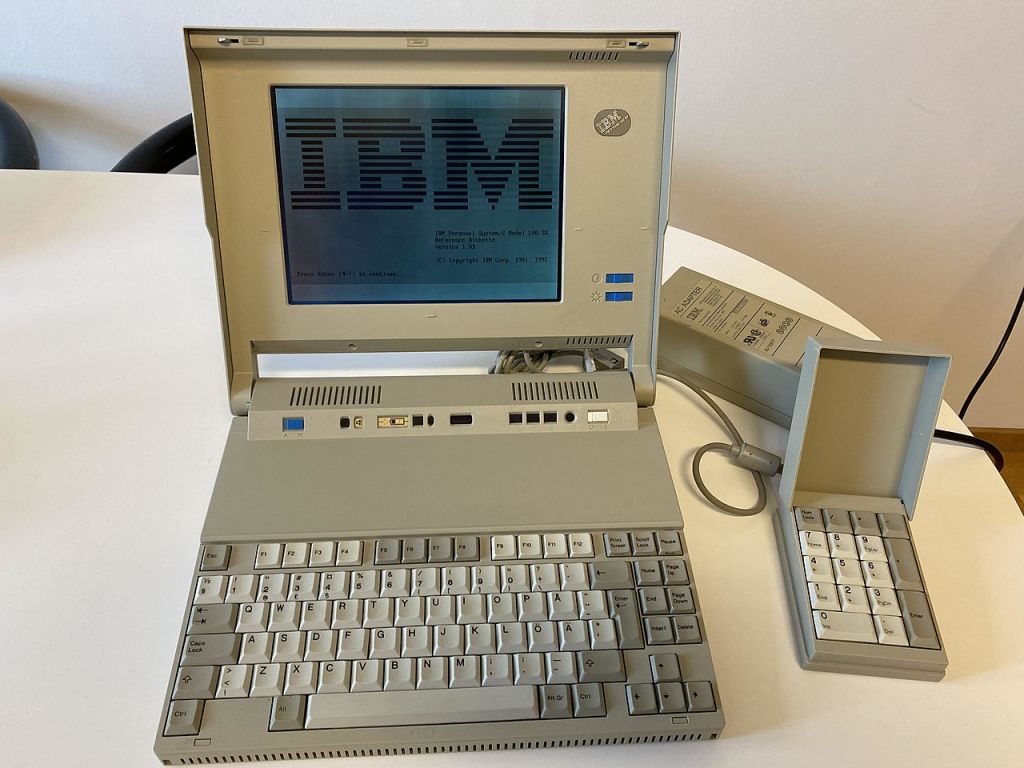

Now, as you can tell by this example. It’s still a fairly sizable beast, and it’s not just because IBM couldn’t condense their technology into a smaller package. It was down to a fear that had resided in the company since 1983, and the PCjr. You see, the PCjr came with a different kind of keyboard. A tiny keyboard. A chiclet keyboard… and consumers despised it. It was intended to be sleek, modern and allow for various keyboard overlay templates to be inserted, which could help the user with text driven environments. But, it bit them in the arse, and IBM did not want that to happen again.

So the L40SX is fitted with as good a keyboard as they could muster, and it’s for that reason that both the keyboard and laptop, are larger than Compaq’s offering. Of course, the real solution was somewhere between the two, and Compaq had already worked that out, by integrating a smaller, but still highly usable keyboard into the Lte.

But IBM did perhaps get this component exactly right for die hard keyboard fanatics, and we’ll take a closer look at how in a minute. The increased case space, also meant that the L40 had enough room for some mighty processing power. The top laptop in the original Lte line-up was a 12MHz 286, but under this baby’s hood is a MIGHTY Intel 386SX, running at 20MHz. Substantially faster, and with up to 18MB on board RAM and the optional 387SX co-processor. The case also allowed for a NiCd battery with more than average running time, and a plethora of ports, including PS/2, 25 pin parallel, 9 pin serial, a VGA out and an external expansion connector, all of which are covered up with these nicely contained flaps. All of this is contained in just 7.7 pounds, which makes it not too much heavier than Compaq’s offering, and it was actually enough for a lot of media outlets to classify it into the Notebook category, with measurements of just over 2″ high, just under 11″ long and 13″ wide. However, according to Deborah Bell and Gerry Purdy, this actually puts it outside of even IBM’s stated maximum notebook measurements of 2x9x12 inches.

Although it feels long, it’s still a nicely constructed machine, and it’s pleasing to look at. Everything’s tucked away. Everything is neat and clean. It was also the first laptop to use a row of LCD indicators rather than LEDs. Not only was this easier on the battery, it also provides visual feedback with icons for the modem, speaker, modem, battery, humidity (which is pretty neat, and will alert you if you’re outside of the 5-95% levels), temperature, hard drive, disk drive, numlock, capslock, screen and suspend modes, and it honestly looks pretty cool. With the LCD blacked out if there’s nothing to report.

The power switch is nearby, with an A/M Switch the other side for selection between manual or automatic mode. In automatic mode the hardware initiates low clock speed during idle period. In manual it runs at the standard, or a pre-defined speed. The 10″ VGA screen itself is a black on white monochrome supertwisted nematic LCD, capable of supporting up to 32 grey scales. It’s 10mm thick and has a cold fluorescent sidelight, which produces some nice colours at odd angles. Thankfully the build in brightness and contrast controls, help with your viewing pleasure, even at some obscure angles, and this is a totally respectable setup for the time.

What’s most noticeable though, or should I say, least noticeable, is just how quiet this thing is. The 250MB hard drive, upgraded from the standard 60MB is barely audible, and sounds more like a triangle being played by a lone band member, 100 metres down the street, than an actual mechanical drive. It’s so quiet, that the conversely noisy floppy drive actually feels jarring and abrupt, amid this serene landscape.

After a memory check, confirming the 2MB on board RAM, The PC boots directly into the IBM DOS Shell. A standard feature of PC DOS, which of course, is the standard OS here, being an IBM machine. PC DOS 6.3 to be precise. Although originally, this PC would have shipped with PC DOS 3.3, 4 or 5 on later models.

By 6.3, PC DOS had diverged from MS-DOS and was doing it’s own thing with different apps for RAM optimisation, editing and the like… and talking of editing, it gives me a chance to demonstrate just how beautiful the standard 84/85 key keyboard is. Not just in it’s construction, but also, it’s feel.

This is, by a country mile, the nicest laptop keyboard I have ever had the pleasure of typing on. It’s so nice that it seemingly reduced my normal typing error level by about half. It’s like skipping over a still surface of slightly resistant water.

Of course, being a laptop, there are no switches here. Instead we get a rubber dome under each key, which buckles with exquisite certainty, allowing you to feel utterly connected with the letters you are typing. IBM were keen to get this right, and boy, did they nail it. I have no doubt that this helped sell this laptop… and sell it did.

IBM had projected to sell around 30,000 of these machines by the end of the year, but in the end, sold over 100,000, and selling significantly more than that thereafter . So despite Compaq’s offering, it was very much a success. Especially when you consider that the retail price for each was nearly $6,000. Just over $11,000 in today’s money.

But then, this is very much a business machine, aimed at getting businesses mobile. It was designed for executives working from hotels, or around a conference table. It certainly wasn’t designed for gaming. As you can see from Paperboy 2 here. The blur on this screen is worse than anything you might have experienced on a GameBoy or GameGear in the 90s. But at least the PC speaker is pleasant, especially combined with some clever use of it, like Paperboy 2 employs. It almost feels like there’s a sound card on board.

If you really did want to game on it, then something like Overlord, or Supremacy is much more at home. Naturally it has no trouble running with the 386 processor installed, and if you wanted to connect it up to an external monitor, then the world is your oyster.

But it’s not meant for that. It’s meant for this… and to aid with that, a few add-ons were available.

One of them is a numeric keypad. It can be connected easily via. the side port, where an optional modem port can also be placed, and allows you to enter numbers quickly that a bookie taking bets on the Running Man. You could also get this rather quirky Trackpoint, mouse that could be used as both a trackball, or standard mouse, depending on your desk, or lack of.

Like a lot of PS/2 machines, the BIOS is a fiddley affair, and settings are tweaked from booting from a reference disk, rather than any built in controls. From here you can run numerous machine tests. You can set the speed of the processor, say if you wanted to run some old software that was upset by the fast paced CPU. This is linked to that A/M switch I mentioned earlier. You can even change the speed of the keyboard repeat, which is a nice level of control. Impressively, this is one of the first machines to incorporate automatic power management features, allowing you to adjust screen and drive time outs and the like.

Not only that. If you close the lid in use, the current applications are suspended, as you’d get on a modern day computing device, leaving only the system memory and real time clock operational. Pretty neat.

Honestly, if I had this laptop in 1991. I’d be happy as a pig in grot. But then, for $6k, you’d hope so. The question is, were IBM happy? They’d accrued more sales than they expected, but by this point, they weren’t hoping for the world.. and honestly, they didn’t get it.

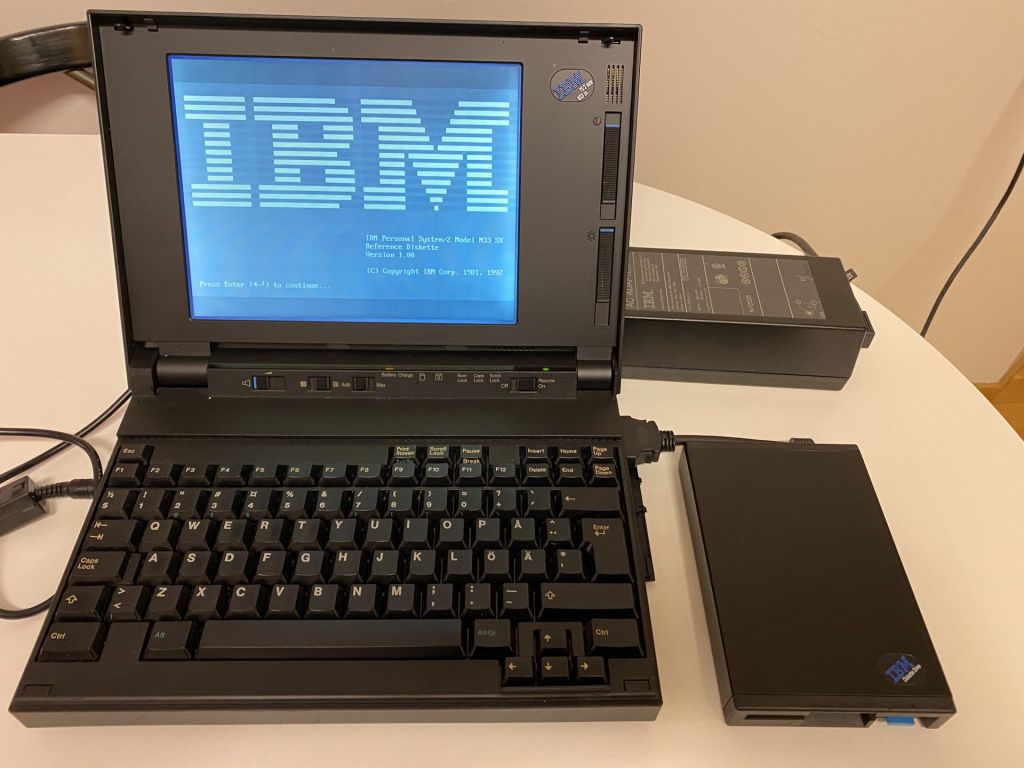

THE L40SX wasn’t the saviour of IBM, but it did pave the path for other machines, and it played it’s part more than you might think. Some pre-production prototypes of the L40SX were actually created in black, rather than this standard PS/2 cream colour. They also had a built in track-point pointing stick and a 10.4″ full color TFT display.

And do you know what other laptops shared these features?

That’s right. The N51SX, N51SLC and CL57SX….

Wait, what’s this? These aren’t Thinkpads. Well where are the Thinkpads? These came first? What? Really?

Ok, so the first laptops that IBM rolled off in their new sensational livery, were less than sensational, and they didn’t actually have the striking red pointing nub. Despite their striking colour, these were actually called “me too” products by the press, once again trailing behind the competition. But, at least, could finally be classified, without question as notebook computers.

Their release was questionable, almost like a tentative test dip into the waters, because just a couple of months later, in October 1992, IBM would finally release the Thinkpad, and this really did change the fortunes of the company. Incorporating many of the features of the L40, including it’s patented power saving controls.

Which was quite lucky, some say suspiciously lucky, because in May 1993, just 3 months after the L40SX was discontinued, IBM issued a recall for 150,000 of the machines after 15 separate short circuits were reported, all of which were strangely, from Europe. It seemed that when the system’s insulation had been damaged, a hole could be burnt in the machine’s casing. IBM offered to repair systems worldwide for free, but recommended that users remove the battery and power only through the AC adapter. Why this took two years to emerge as an issue seems strange. Perhaps IBM were keeping hush or more likely, this was degradation due to time. A bit worrying given, I’m using one that’s 30 years old. Let’s hope it was a repaired model, because sadly, there aren’t many of these beasts left. Most of them scrapped by the businesses that bought them.

The L40SX may have been a stepping stone. But it was a stepping stone with a damn nice keyboard, and if you get a chance to try one out, I wholly recommend it.

Until next time, I’ve been Nostalgia Nerd. Toodleloo.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.