1989 was a time when the Amiga 500 was beginning to take off at a rapid rate, and where the powerful technology was finally being seen for the power house that it was.

Given its superiority to almost everything else on the market, especially in terms of graphical power, its easy to forget that the technology was now 4 years old, and this slow start meant the Amiga still had an uphill struggle on its hands.

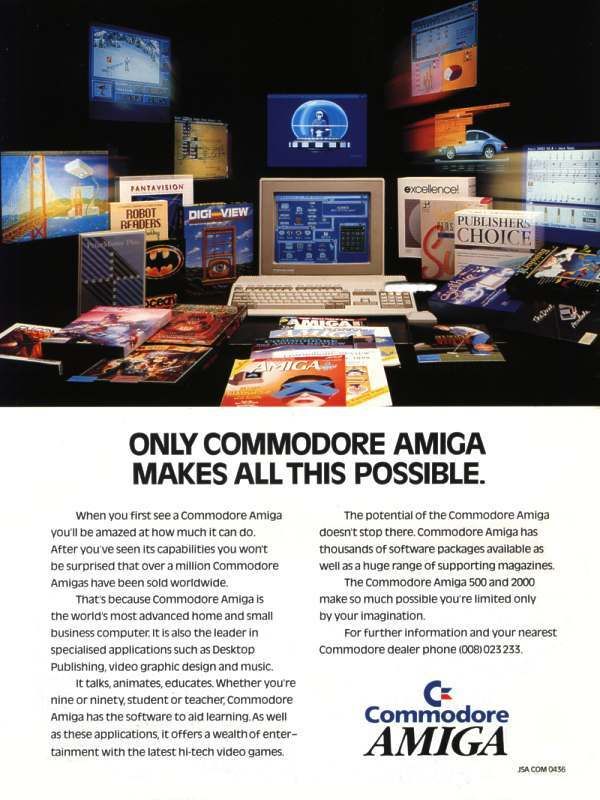

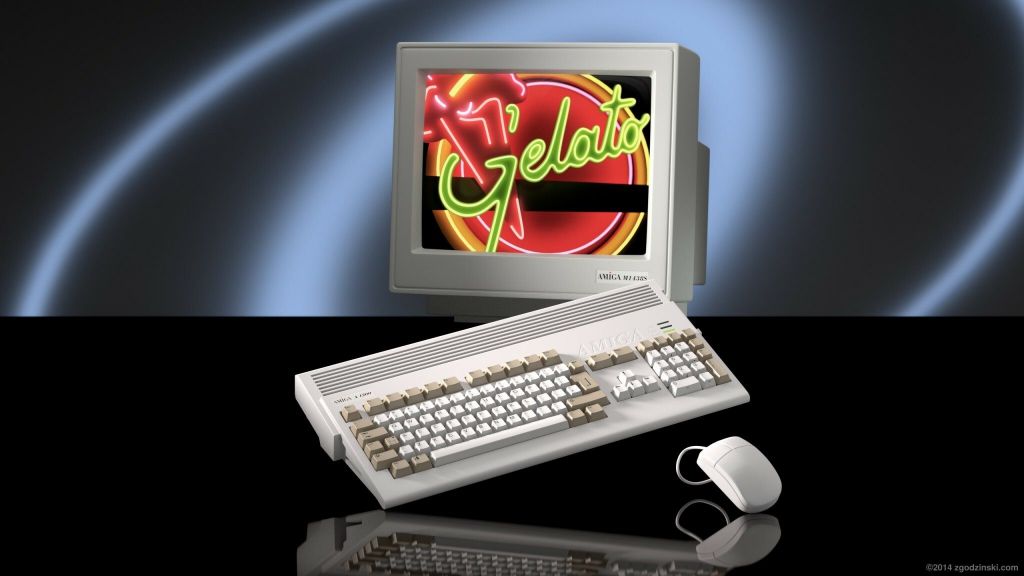

Gaming was where the money lay, and the Amiga 500 Batman pack, launched by Commodore UK, had positioned the 500 as the must have computer for that purpose. Most 500 packs before this point required the consumer to purchase the additional RF modulator, but given that vast majority of households would hook machines directly to their televisions, just like their Spectrums and C64s, this inclusion was pivotal. The graphics and sound were flying high above the existing 8 bit competition and the Amiga was leading the way among reviewers, the press and exhibitions. As 1990 ticked over, the Amiga 500 was shifting some 300,000 units a year throughout Europe.

Over in the United States, things weren’t quite so rosy, with sales of the 500 a fraction of their UK counterparts. Commodore of America hadn’t positioned the 500 as a gaming machine quite as well, in part due to lackluster advertising. In part due to uncompelling bundles and in part due to the popularity of the NES for gaming and the IBM PC compatibles for other computing tasks. In Europe the Amiga was a natural progression in a world filled with ZX Spectrums, Commodore 64s and a submissive array of 8 bit consoles. IBM compatibles over here were seen almost exclusively as professional machines with a prohibitive cost, whilst at £499, the 500 was now affordable for a significant portion of the middle and working class.

The Amiga 2000, on the other hand was fairing reasonably well in the States, working its way into professional graphics use for businesses, production houses, education and scientific establishments alike. The demand for greater power spawned an update in the form of the Amiga 2500, which was simply a 2000 fitted with a 68020 or 68030 accelerator card. Still, although it was a fairly impressive machine at launch, it was still not enough for many new applications and limitations to the design meant that although the machine could be upgraded to 9MB of total RAM, the custom chipset could only directly access 512kb. Jay miner had even expressed his dissatisfaction over the somewhat pitiful improvement the 2000 had actually brought, making it known that he and consumers expected and needed more.

Before leaving Commodore, and almost immediately after the launch of the Amiga 1000, Jay had reportedly begun work on a successor to the already revolutionary chip-set. This successor was code-named “Ranger” and although its widely reported to have been a brand new 32 bit architecture based around the Motorola 68010 or even 68020 CPU, it was more an increase to the expansion capabilities of the original chip-set. These were really the capabilities which came to fruition in the Amiga 2000 itself, leaving the actual base chipset not quite as advanced by 1989 as they were some 4 years prior.

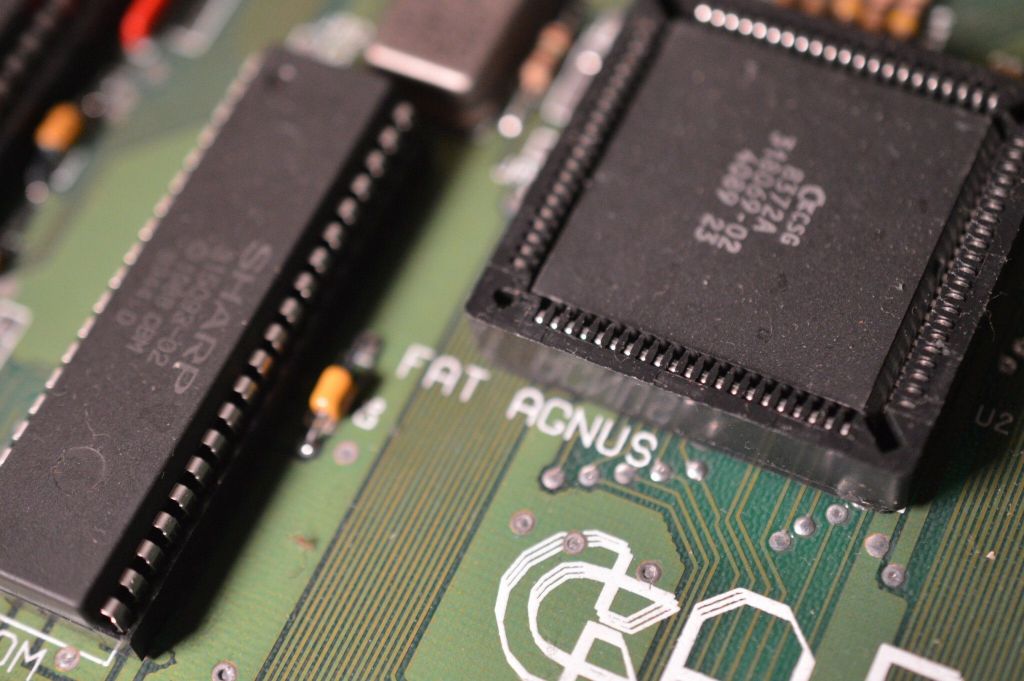

With the Original Chip Set limited to accessing just 512kB of Chip RAM, later iterations for the Amiga 500 and 2000 introduced the Fat Agnus chip, which allowed an additional 512kB pseudo-fast RAM upgrade that could only be accessed by the 68000 CPU, but crucially only via. the congested Agnus bus. Because of this its commonly referred to as slow RAM, and as its not tied to Agnus, its use is somewhat limited if you want to store data directly from the custom chipset, such as GFX or sound data for example. This was essentially a hack of the original chip set, but the next version would circumvent this limitation by employing a new Fatter Agnus chip (also known as Obese Agnus), but its also the point where things get a little messy. Fatter Agnus is capable of addressing 1mB of chip RAM directly and was fitted to Amiga models in 1989 from revision 6 onwards – although some of these machines require jumper changes to fully enable this. These changes, sometimes referred to as the “Half Enhanced Chip Set” were made unbeknownst to the average consumer at the time and were followed by a range of minor board revisions culminating in the arrival of the full Enhanced Chip Set in 1990.

Although an incremental update, this chip set is really the official second generation of Amigas. Developed at Commodore’s American Head Quarters, the ECS integrated the Super Agnus, capable of now addressing 2mB of Chip RAM and a Hi-Res Denise chip. To go with the additional RAM space, the blitter could copy display regions larger than 1024×1024 pixels in one operation and display sprites in border regions. Denise could now pump out a “productivity” resolution of 640×480 without interlation, akin to the standard IBM PC compatible VGA resolution which Windows 3, released in May 1990 was able to run at. In addition, Super Hires at 1280×256 or 1280×512 interlaced was now possible along with other custom scan rates. These were all welcome additions, which particularly helped the productivity and graphics applications, Commodore of America were still keen on pursuing, but did little to benefit the games market currently booming over in Europe.

Compatibility wise, ECS was intended to be fully compatible with OCS software, but the changes did mean that the odd title refused to run, and given that some revision 8A Enhanced Chip Sets made it into 1991 production run 500 models, it caused a degree of headache for the odd consumer unaware of the changes lurking under the hood. The first official machine to integrate the technology was the Amiga 3000.

Released in June 1990 the 3000 was the culmination of work by David Haynie who had begun work on the Zorro III expansion bus architecture in 1989 continuing the AutoConfig standard from the 2000 series, allowing a similar experience to the plug & play PCI bus on IBM PC compatibles. Alongside Greg Berlin, Hedley Davis, Jeff Boyer and Scott Hood, Haynie’s vision for the 3000 was quite an overhaul to the original Amiga specifications and was designed as a high end workstation from the outset, much in part due to demands from current 2000 owners. The 68000 CPU was replaced with the new 32 bit Motorola 68030 processor in either 16 or 25MHz flavours, alongside a 68882 maths co-processor and 32 bit memory bus. Alongside the 2mB capable Enhanced Chip Set, fast RAM can also be added up to 16MB and with there’s plenty of room in the case for a SCSI hard drive, twin floppy drives in either double or high density, as well as all the connectors we expect from the Amiga machines. A custom chip, called Amber also removed flicker from the video output and allowed display on cheaper VGA compatible monitors.

Kickstart 1.3 had been order of the day since 1988, and is the go-to ROM for compatibility of older game titles, but the 3000 was almost witness to version 1.4, which increased the ROM size from 256kB to 512kB. However Kickstart 1.4 and the tied in Workbench 1.4 remained in the prototype stage, although this may explain why the 3000 required booting Kickstart from floppy or hard drive to be bootstrapped into memory, just like the original 1000 machines. Kickstart 1.3 was included on early iterations, with the fully fledged version 2 included on releases from late 1990 onwards.

The 3000 was a pretty impressive machine, but again hand in hand with it’s ECS capabilities was aimed at the professional market as a high end graphics and video workstation, thanks in part due to the genlock capabilities of the 2000 model and the release of NetTek’s video toaster towards the end of 1990. Its uses were wide and varied, including rendering for various television and film productions and also forming the basis of the W Industries Virtuality machines we all gawped at and even got the chance to play for several pounds per play in high end arcades, for me, being Pleasurewood Hills near Great Yarmouth….. I’ll be honest, it was a bit of a let down. The high price tag of these machines meant that sales figures weren’t huge, but the technology did ensure that the Amiga brand was still stepping forward, albeit with a smaller stride than the leap brought about with the original hardware. This was at a time when other platforms had adopted somewhat of a Monty Python gait, and were catching up fast in terms of both operating system and technical ability, and still bounds ahead in terms of sales.

Who’s in Charge?

[dropcap style=”font-size:300%;color:#9b9b9b;”]Y[/dropcap]ou’ll remember that since ousting Thomas Rattigan – guy who began to turn Commodore Amiga around – Irving Gould was still holding the reigns as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, but in 1989 had appointed Mehdi Ali as the new company president, a former managing director of investment bank Dillon, Read & Co, and with the typical fashion expected of 2 investors, Commodore International continued on a path of clueless money pinching, misguided decision making and resource appropriation. One such example is with the Amiga 3000UX; an Amiga bundled with Amiga Unix, itself a port of the AT&T System V. Sun Microsystems approached Commodore offering to package the UX as an alternative to their high end Sun Workstations, but Ali’s insistence on extortionate licencing fees killed any deal and destroyed the Amiga’s chances of penetrating the Unix marketplace. Management then careered on pushing on with some spurious hardware designs, as only an investor would, in an apparent attempt to expand and diversify. Unfortunately, this move was as far removed from the gaming success seen in Europe as possible.

With the luxury Amiga 3000 yacht bobbing along in the Ocean, focus was moved to a brand new take on home entertainment. Commodore’s only machine to really penetrate a mainstream market – the Amiga 500 – was still speeding off on the other side of the water and the Commodore 64 was winding down tied to the banks, still serving the lower end market in small numbers. So we can envisage this new concept as some kind of house boat, lumbering onto the scene, much to everyone’s bewilderment.

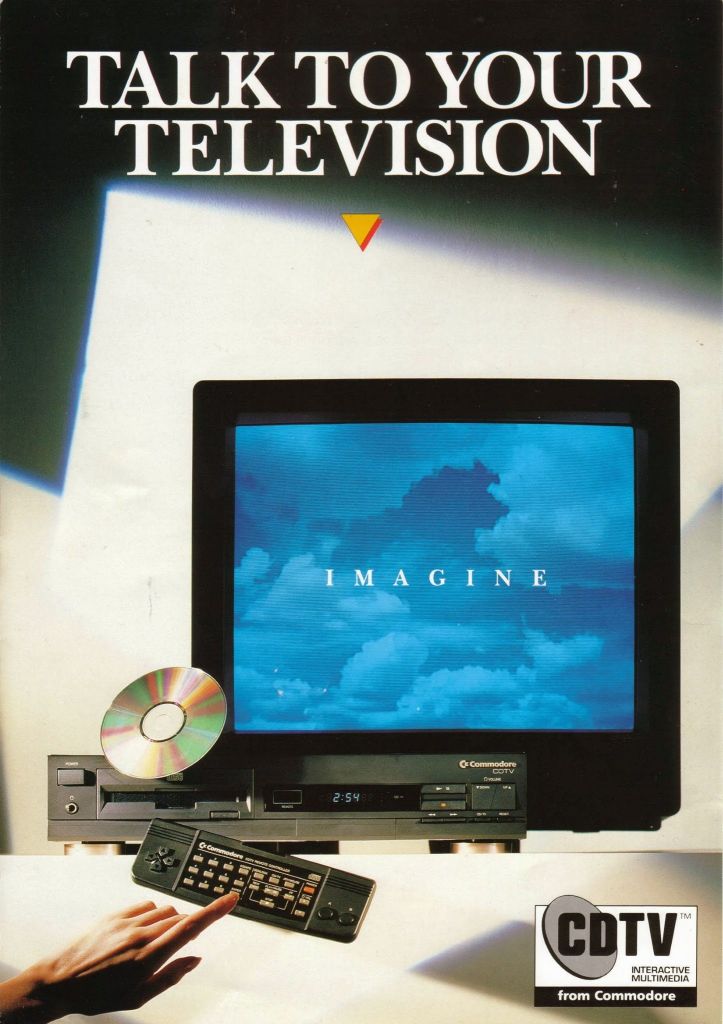

This house boat, was of course the Amiga CDTV – the Commodore Dynamic Total Vision. A concept which had been in development since July 1989 when Gail Wellington – otherwise known as “The Mother of the Amiga” and formerly head of the Commodore UK’s technical department, met with product developer Don Gilbreath to draft out the new concept. After design in Japan, the machine first popped up as the CDA-1 prototype in various magazines during May 1990. At this stage the black, VCR style box was dubbed an “Interactive Graphics Player” and it was Commodore’s attempt to create an entire new market, before the market itself was even established. This market was the area of multimedia home entertainment, and although you have to give credit to Commodore for their innovative thinking, it was a risky move that would prove as ahead of it’s time as Clive Sinclair’s dinky little pedal car.

Now, although Irving Gould can often be portrayed as the evil villain of Commodore who brought about their downfall, which is almost probably correct – especially with his new accomplice – he did recognise that the biggest market for the Amiga was Europe. The management and their apparent lack of knowledge just didn’t seem to work out that the smart thing to do was expand on the already successful gaming market, rather than muddy and smear it about a bit. So with the consumer device in mind, almost 2,000 CDTV preview machines were shipped into the UK in October 1990 for press and public testing. The plan was to capitalise on the new multi-media features of CD-ROM and plonk it right into the living room. Commodore even decreed that CDTV units should not be placed within 30 feet of computers in store. This was an entertainment unit, designed to sit under the family television. Given the Amiga’s capabilities, adding a CD-ROM seemed like the perfect formula for multi-media bliss, and indeed an upgrade for the 500 may well have been just that. But as a standalone unit, the CDTV brought about its own problems.

The system was essentially an Amiga 500, based around AmigaOS 1.3 but with a CD-ROM drive instead of a floppy and a remote control instead of a keyboard and mouse. It was largely compatible with existing Amiga titles if you bought a keyboard, mouse and floppy drive, but at £699 initially and $999 in the United States excluding these items, a price that was reduced to £499, it was a pretty expensive splurge. Consequently, gamers stuck to their Amiga 500s, or snapped up one of the new Sega Mega Drives for a fraction of the cost, and everyone else, just didn’t know what it was for, happy and content with their video recorders and massive library of VHS titles. The CDTV did actually allow video playback via. CD-ROM through Commodore’s CDXL format, however the quality was below that even of VHS and unsuitable for anything of usual running length. Multimedia games and entertainment was the sales pitch Commodore tried to force, with the fact it doubled as a CD player being quite a strong selling point back then. There were of course takers who were keen to get their hands on the latest shiny technology but even with some press outlets hailing it the technology of the future, sales and verdicts were disappointing.

It was actually our old friend Nolan Bushnell who had been brought on to manage the recently formed “Interactive Consumer Products Divison” of Commodore at this time and he was, as you’d expect, an avid endorser of the technology stating “CDTV will truly change the way people learn and are entertained. It’s the real new media of the nineties”. Peter Black, who was president of Xiphias Corporation and responsible for porting their “Time Table of HIstory” from the Macintosh CD-ROM to the CDTV was also keen to point out that “the CDTV would be on the market a year before the Philips CD-I”, although there were early warnings, with the Macintosh CD-ROM market performing poorly at the time, having sold only 2,000 CD add on units in the first few months of launch.

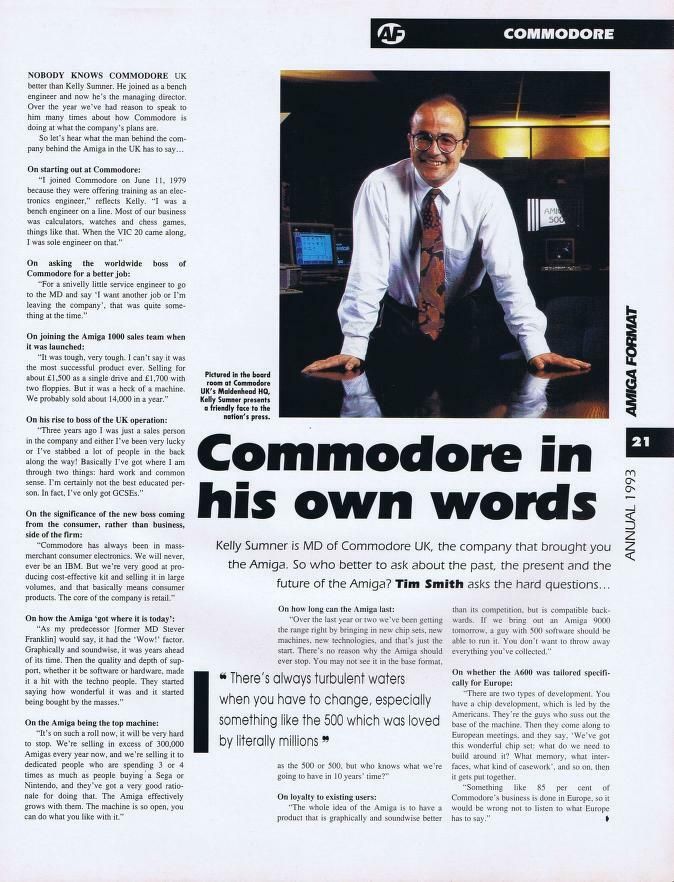

The system’s official launch was January 1991, and Commodore even ran a trade in campaign for existing Amiga owners, but 2 years of struggle, poor quality titles and the very odd, reasonable game, meant it was discontinued by 1993. The Philips CD-i machine, released in December 1991 was a similar, if not slightly more capable system, and impressively clung on until 1998, with a slightly more directed and clear marketing approach. Kelly Summer of Commodore was quoted as saying “We got the basics wrong. Wrong price, wrong spec, no support”, which was partly true, but it was still a mis-placed product and David Pleasance noted that the expensive advertising campaign was off cue, confusing the public by trying to convince them it wasn’t a computer at all. Commodore tried to rectify this later in 1992 by adding the Amiga brand before the CDTV name and bundling a keyboard and mouse as standard, but it wasn’t enough. In the UK, the CDTV sold just over 30,000 retail units – a similar figure to Germany – and Plans for the improved, full ECS based and cost reduced CDTV-II were scrapped, so focus could be shifted back to the more successful and conventional lines.

However, the CDTV wasn’t the only strange thing to emerge from Commodore International under Mehdi Ali’s fumbled leadership. The lack of R&D funds meant rather than concentrating on cutting edge technology, the older Commodore 64 tech was looked at for advancement. The period between 1990 and 91 not only saw the development, and subsequent cancellation of the Commodore 65 – an upgrade of the C64 which seemed to have no place next to the Amiga, but also the launch of the Commodore 64 Games System, aimed at the console market. I don’t like to borrow quotes, but WHAT WHERE THEY THINKING?

But it wasn’t only Commodore International who were coming up with strange designs. Commodore UK actually launched an Amiga 1500 in 1990. Based around the 2000, this machine shipped with two floppy drives instead of a hard disk and really did little apart from confusing the range. Some believe it was pushed out as a lower cost desktop, to try and kill an A500 desktop conversion kit introduced by Checkmate Digital and named the A1500, others suggest that Commodore just had a lot of spare floppy drives laying around. Either way it was another bizarre foray into the world of general purpose business machines which they had never had much success with.

Amiga Was Looking to Dominate

[dropcap style=”font-size:300%;color:#9b9b9b;”]1990[/dropcap] to 1991 wasn’t all doom and gloom though. It was an exciting time and with Commodore selling 1 million Amiga machines throughout the financial year in total – half as many as they’d sold in total previously -, it was still their best sales period, and really the high point for the technology. Revenues for 1990 stood at $887 million dollars and $1.5 million dollars profit. By 1991, revenue rose to over $1 billion dollars, but with reduced R&D profits rose massively to almost $50 million dollars. Especially in 1990, Commodore seemed keen on keeping themselves incredibly busy creating a more expandable A3000 Tower model and various prototypes such as an upgraded A3500 Tower machine, the A1000 Junior, a low cost desktop based on the Enhanced Chipset and the Acutiator modular system designed by David Haynie. But the 500 over in Europe was by far their main cash cow and the growing user base hadn’t only increased Commodores fortunes, it had also created a rolling ball effect with some of the best titles on the platform beginning to emerge, creating a knock on momentum gain for the brand.

Software houses like Cinemaware kept pumping out ever refined releases along with Lucasarts, Magnetic Fields, the Bitmap Brothers and of course, DMA Design, with a range of games which really came to define The Amiga and herald a whole swathe of computer gamers, who like the Commodore 64 some 10 years previously, could reap the benefits of a computer, whilst still being ahead in the gaming stakes.

You’d expect titles like this to herald a run-away success for the machine. The Atari ST was by now floating around with only 1 paddle, even with the launch of the improved STE model, which brought the hardware up to Amiga capabilities, software house allegiance had jumped to the Amiga in droves, leaving Atari struggling frantically to keep up. But a new breed of console competition was gaining momentum, and with its lower cost, incredibly cool advertising and exclusive titles, it was gaining it at an incredibly rapid pace. 1992 would need to be a even more special year.

On the books, 1992 was an incredibly special year for Amiga. But fate it seems was rolling unfavorable dice, some of which was unavoidable.

The first surprise would come in the guise of the Amiga 500+, released in January 1992. With the rise of the IBM PC Compatible, and the earlier launch of the Sega Mega Drive and Super Nintendo. The Amiga, as a games platform, was now falling into obscurity in North America, therefore the 500+, although released in several areas, including most obviously in Europe, wasn’t officially available in America, rubbing salt into the wounds of US Amiga gamers, who already had trouble running PAL games on their equipment due to the incompatible signal formats and now had to manually botch an upgrade their 500s in order to play the latest software!

With manufacturing improvements, the 500+ was actually cheaper to produce for Commodore and brought us the ECS chip set, fitted with 1MB as standard along with the brand spanking new AmigaOS 2.04. Kickstart 2 brought about a range of new features, including the ability to enter a boot menu at power on, the integration of the 880k Fast File System into ROM and a range of improvements to operating and memory protection. Given the fragility of the Amiga’s early multitasking, previous development manuals had shipped with a warning;

[quote style=”font-size:110%;”]”The Amiga operating system handles most of the housekeeping

needed for multitasking, but this does not mean that applications

don’t have to worry about multitasking at all. The current generation

of Amiga systems do not have hardware memory protection, so there

is nothing to stop a task from using memory it has not legally acquired.

An errant task can easily corrupt some other task by accidentally overwriting

its instructions or data. Amiga programmers need to be extra

careful with memory; one bad memory pointer can cause the machine

to crash (debugging utilities such as MungWall and Enforcer will

prevent this).”[/quote]

Programmers essentially had to manage the memory themselves, which was an upheaval for those used to single task environments of the past. Rather than hogging resources, programmers now had to request the OS for procedures and this is what led to many of the errors Amiga owners became familiar with. One way to get round this was to avoid the OS completely and program to the metal as if the Amiga was a single tasking entity, but this also led to compatibility issues when systems were upgraded or changed. Hence the upgrade to AmigaOS 2 did cause a fair degree of incompatibility with games programmed this way, leading to the need for switchable ROM boards or boot disks such as relokick to effectively “downgrade” the Kickstart back to version 1.3. Version 2 was by no means a complete fix for future errors, but significantly for some it did herald the removal of the “Guru Meditation” error, replaced with a much more mundane message. Perhaps the most striking difference was the startup boot request and general visuals of the new Workbench desktop. The original high contrast environment was very much designed for fuzzy monitors and televisions, however with new higher quality displays, a more elegant approach was implemented.

The 500+ would also see Amiga’s second best selling bundle. The familiar Cartoon Classics pack, complete with The Simpsons, Captain Planet and the key titles of Deluxe Paint 3 and Lemmings. Deluxe Paint 3 was a significant improvement for the series, introducing animation and HAM abilities, and combined with the tank mouse, like the Batman pack, this bundle introduced a pool of 90s kids to the wonder of digital creativity. Given Commodore had dropped the underwhelming and error prone Amiga BASIC from Workbench 2, you could also grab yourself GFA Basic, Photon Paint 2 and an arcade games pack with the Silica Systems bundle. The suggested bundle price was £359, but this was a time when 3rd party vendors were going out of their way to make their offers more appealing than their competitors and it brought about a welcoming wave of price wars, and pages and pages of salivatingly tempting goods. Man, the early 90s. What a time.

Fancy a Party?

[dropcap style=”font-size:300%;color:#9b9b9b;”]It[/dropcap] was also the time which witnessed the ever growing peak of two homegrown scenes. These were the Public Domain and the Demo scenes. Public domain was running ahead at great speed thanks to the lack of licencing on the Amiga, with coders trying their hand at software creation before sending it off to one of the vast PD libraries for redistribution. Usually without any monetary reward for their hard coding hours. But the demo scene was something different. Although it emerged on earlier 8 bit systems, in its current guise, it was more or less a descendant of the virus, which emerged on the Amiga way back in 1987, as coders devised more and more ingenious ways of exploiting the machine’s hardware. Disks and disks of demos became available from various groups each trying to out-do each other in the graphical and sound stakes. Sometimes fighting competitor machines such as the ST, but also trying to beat other Amiga coders. These demos really exploited the bare metal coding which Commmodore was trying to keep people away from, but it made amazing things possible.

Like the 8 bit cassette tape scene, this was also an era of pirating, or cracking. Something that is often attributed to the demise of the Atari ST, with its standard MS-DOS compatible file system. But thanks to programs like XCopy it was perfectly possible to duplicate most Amiga disks, and there was an entire black market of people pirating games and condensing them onto single floppies. Groups like the Medway Boys weren’t just prolific on the ST scene. The cracking scene actually went hand in hand with the demo scene as groups clambered to post their latest impressive visuals and soundtracks on the loading screens of games. Those who wanted their games cheap, also got a healthy injection of demo finesse, and were probably all the more enlightened because of it.

Although Bulletin board systems were available, which offered some “questionable” downloads, including disk magazines, created and distributed by each group, the phone prices were expensive, as was the technology to access them, so these scenes also created their own wake of Demo and Copy parties, where people would lug their machines to large venues to share their code, to see what other people were producing, or to just copy mountains and mountains of floppies. Its in this sort of environment that we witnessed many of the great programmers of the time and of today. A breeding ground of creativity and love, for the freedom brought by this new hardware.

Fighting the Consoles

[dropcap style=”font-size:300%;color:#9b9b9b;”]E[/dropcap]lsewhere, away from the crazy copy parties and with the relative security brought by licenced cartridge games, the Super Nintendo was wangling its way into households alongside Sega’s Megadrive. Whilst in the higher end computing scene, Intel’s 486 processor combined with VGA graphics were morphing the IBM PC Compatibles into not only a productivity pack horse, but also a formidable gaming platform, with a much greater scope for upgrade than any existing platform. In fact even though machines like the ST and Amiga usually had better versions, MS-DOS accounted for 82% of computer game sales at this point… although this was heavily slanted by American figures. Over in Europe the balance was more even.

Some 7 years had passed since the Original Amiga, and on the surface of it, very little had changed with the hardware. Owners and press were beginning to feel a little uncomfortable with the platform’s future, and so it was with open arms that several new machines were welcomed by the latter part of 1992.

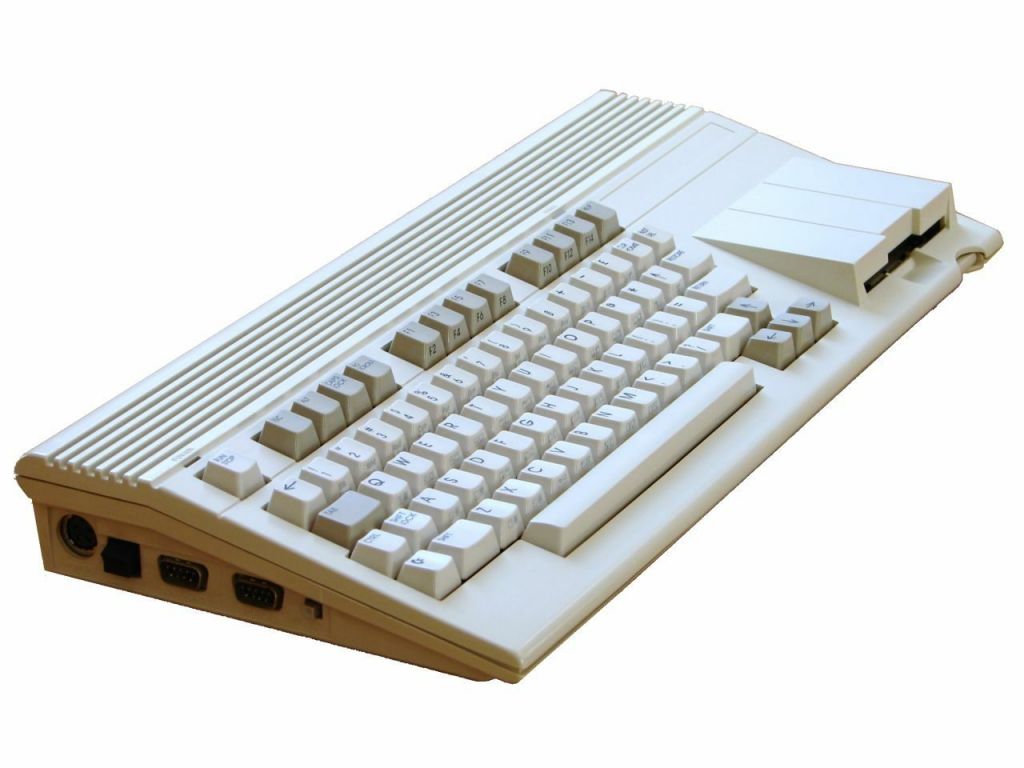

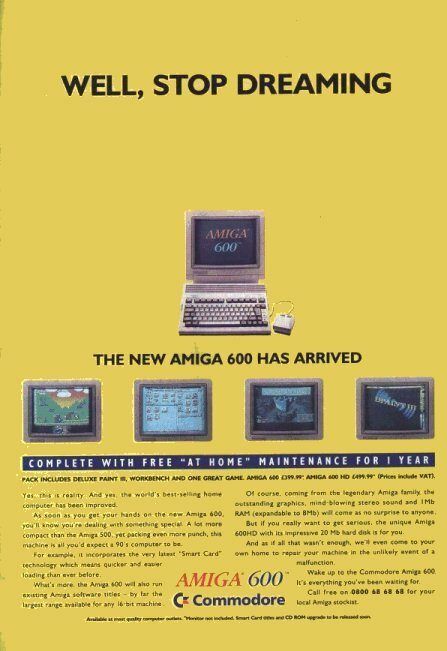

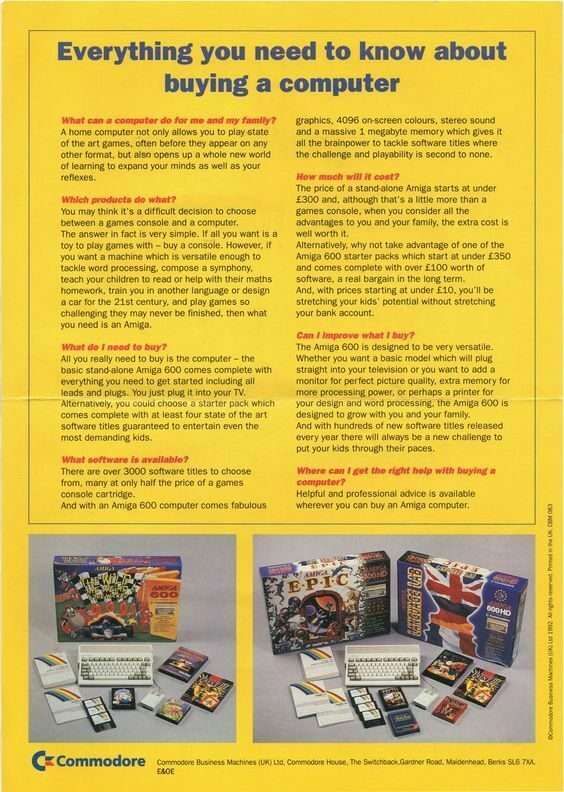

The first was a bit of an odd ball, in that it was essentially just an Amiga 500+, but in a smaller case. The Amiga 600 was intended to originally be the Amiga 300. A low end bottom of the range version of the 500, designed to compliment the 500, and take on the lower cost 16 bit consoles. However, higher than expected costs meant it would actually be sold at a higher price than the 500 and was therefore renamed and shipped as a replacement for the 500 range, leading to the 500+ being one of the shortest living systems, at just under 6 months. The 600 was launched during the March 1992 CeBIT show and was in the shops by the summer for a whopping £399, missing the console price point entirely. Despite this and the lack of numeric keypad, the 600 did have some advantages, such as the capacity for an internal hard drive, side PCMCIA slot and a built in RF modulator. The price point was quickly dropped to £299 and then to just £199, infuriating original buyers, but bundles such as The Wild, The Weird & The Wicked, helped sell machines with similar line-ups to its predecessors.

Almost immediately after launching the Australian built 600s, Commodore announced two higher power machines before the end of the year. This of course, caused consumers to wait rather than buying the 600, and led to increased financial pressure, resulting in the closure of their Australian office to cut costs. The technology for the new machines had actually been on the agenda for some time…. Hopping back to 1989, in what seems to have been some kind of nexus point for the brand, Commodore had begun creating a new state of the art chipset. This technology was designed to retain Amiga’s cutting edge credentials and address critics of the lacklustre upgrades seen since 1985. This “Triple A” Advanced Amiga Architecture was designed to break from the original custom architecture and would only be compatible at a basic level with previous software. In line with previous designs, a set of custom chips was conceived. Andrea, Linda, Mary and Monica, but the setup was conceived as a much more modular approach, similar to IBM Compatibles, allowing for easier upgrade routes. However parallel to this, a Commodore International team headed by Bill Sydnes – the new head of engineering – were also working on the Pandora chipset. Later changed to “Double A” chipset, standing for Advanced Architecture. This architecture was an incremental upgrade, like ECS designed to offer an upgrade on the Amiga 3000 hardware, but with a number of significant improvements.

By 1992, the AAA chipset was looking like it would only be slightly faster than the much easier to implement, and fully completed AA chipset, and so was cancelled in favour of a new Hombre chipset based on a PA-RISC. The AA chipset was then gifted a name tweak to AGA, to emphasize the improved graphics abilities (whilst avoiding potential trademark problems with a well known automobile company), and the Amiga Advanced Graphics Architecture was launched in August 1992 in a high end 3000 replacement; The Amiga 4000. The AmigaOS was now at version 3, featuring improved visuals and colour options along with CD support and a new datatype system. Under the hood the faithful Denise chip was replaced with Lisa, and Agnus with Alice offering a logical step up on the hardware, and one which if released a couple of years prior could have made as much impact as the original hardware in 1985.

The 32 bit AGA architecture was actually cut down from what was originally intended. Prototypes of 3000+ units show support for a digital signal processor and 16 bit stereo hardware CODECs similar to what Atari had just released with their impressive, but expensive ST upgrade, The Falcon. But like Atari, both companies were going through a barrage of cost cutting exercises. Profits throughout 1992 had almost halved since 1991 and market share was being lost to the ever expanding competition. The AGA chipset offered a number of significant improvements over previous Amiga machines, and still provided the niche graphics and video advantages the platform was known for, but nothing that would send the competition packing and lacking flicker free higher resolution modes that other similar priced systems now had as standard. The A4000/040 sold for almost £2,500 putting it at the upper price point even for IBM PC Compatibles, meaning its penetration was again, limited and specialist.

The Last Chance Saloon for Amiga

[dropcap style=”font-size:300%;color:#9b9b9b;”]On[/dropcap] 21st October, an entry level AGA machine – the A1200 – was released in worldwide regions, including Japan and America. But as you’d expect, it was Europe, and mainly the UK in particular where interest spiked. Existing Amiga owners weren’t keen to jump to consoles, and IBM Compatibles were still eye wateringly expensive. At a base price of £399 in the UK (or $599 in the States) the 1200 was a tantilising prospect, and this seemed to be a rare instance when the technology was right, the price level was right and the brand name was right to really make an impact. And it did. Demand was very high for the system, particularly in the UK for the Christmas ’92 period, but our old friend “production problems” meant only 30,000 1200s were available at launch, spilling orders over to 1993. With the CDTV discontinued this was also the year that that A570 CD-ROM drive for the 500 was launched. Designed to be compatible with CDTV software, it was late to market and actually released after 500 was discontinued, but given the existing user base of some 2 million owners, it was deemed worthwhile. Uptake was limited but started the wave of compilation CDs containing hundreds, if not, thousands of PD programs, demos and images which caused myself a considerable drooling frenzy. This was exactly the pairing that could have made the Amiga a run-away success in the 90s if it had come instead of the CDTV. The existing user base could have witnessed amazing enhanced versions of Cinemaware games brought to fruition amongst others, rather than limited to the cramped conditions of a floppy disk, and arm aching disk swapping sessions, but like most of the Amiga story, it was in slightly the wrong place at the wrong time.

The start of 1993 witnessed a price cut of all non AGA machines, but the AGA line continued to sell well with over 100,000 machines sold by March. However, this was not enough to off-set the seemingly spiralling profits. With the 500 discontinued and the 600 already an out of data technology, reliance was heavily placed on the performance of the new hardware. But this was still an era of vast competition, all trying to make strides in new innovations. Although the 1200 sported a Motorola 68020 processor, it was still a CPU originally released way back in 1984, before the original Amiga was even on sale. By now Sega’s Mega CD add-on was available, demos of the new 3DO console were showing us what the future held and Atari having discontinued the Falcon were whispering something about a 64 bit Super Console. These machines would come to fruition before the year was out, but not before Commodore finally got a grip on what the market had been demanding all this time. A cutting edge games machine. The idea originally tossed around between Jay and the Amiga team back in 1982 still seemed to be the way forward some 10 years later.

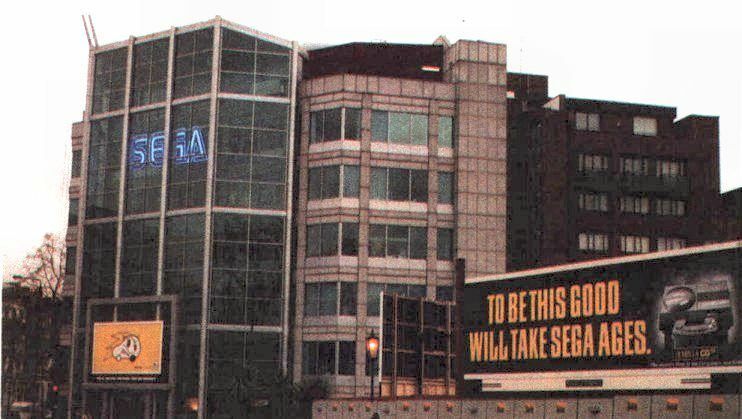

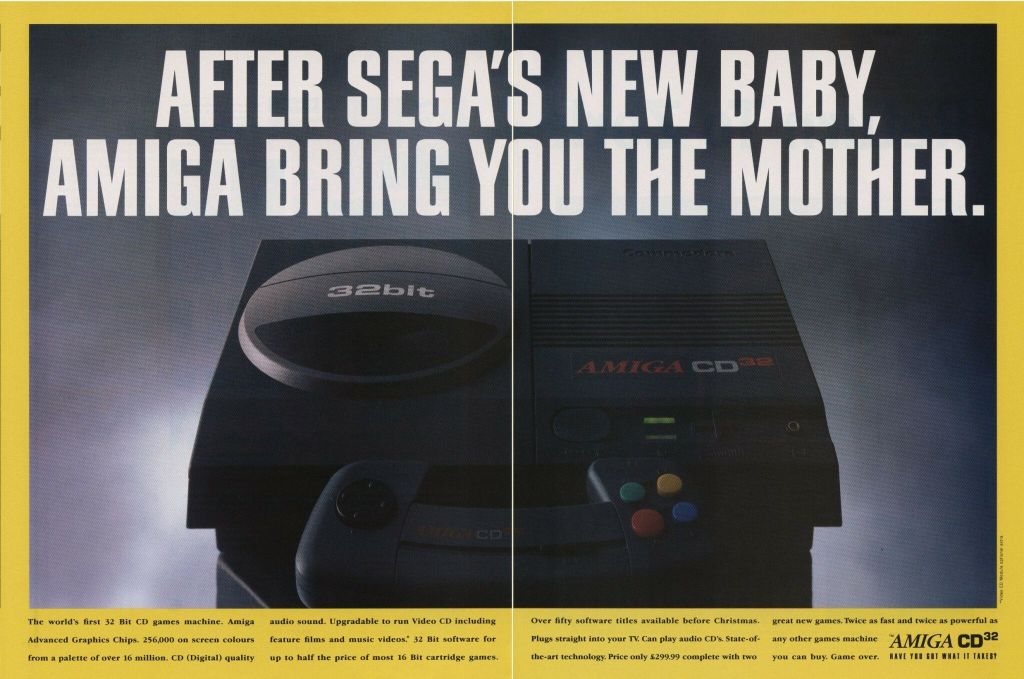

Codenamed Spellbound, the CD32 was announced at the London Science Museum on July 16th 1993 and released in September at the World of Commodore Amiga show, beating both the 3DO and Jaguar to the post and claiming the title of the first 32-bit CD based games console released in the European region. It also significantly undercut the competition in terms of pricing launching at £299, the same price the A1200 was also lowered to. Compared to a Mega CD at £369, with the cost of a Mega Drive on top, this was a significant saving, and it led to substantial sales for the compact, keyboardless, Amiga 1200 in a grey box. The machine’s similarity to the 1200 was one of the reasons Commodore were able to get the machine out to market so quickly and David Pleasance, along with Commodore UK entered an aggressive marketing strategy akin to Sega’s Nintendo slating approach from a few years prior, even erecting a huge billboard outside Sega UK’s office playing on Sega’s own marketing slogan.

Although the CD32 was largely cross compatible with the A1200, a new Akiko chip was added under the hood. This little chip was able to perform to “Chunky to Planar” conversions, which would ordinarily consume many cycles of the 68020 processor. It was requested by Amiga’s software group as most software was currently being developed in chunky pixel mode, suitable for PCs – this function converted these “Chunky Pixels” to Amiga bitplanes, allowing 3D based games to run faster than a base standard 1200. The Amiga hardware may have been incredibly optimised for 2D, but these same optimisations proved somewhat of a hinderance for the new 3D games emerging and although Akiko was a helpful addition, it would still be unable to keep up with the technology that was just around the corner. What the system did have, was a wealth of existing Amiga titles that could be easily adapted to the console, which was both a great selling point, but like the other super consoles of the time, a downfall, as the technology didn’t seem to improve on what we already had. Titles that shipped with the CD32 bundles completely failed to cast the machine in a respectable light. Despite this, the console sold well, as gamers clambered to get their hands on the a machine that would fulfil their playground boasting requirements.

The console was also launched in Canada and although planned and advertised in the United States, a legal dispute with Cad Track over their use of the XOR cursor technique (used for displaying the cursor over the background image), prevented the machines being imported from their Philippines stock pile until a $10 million settlement was paid. Despite the tenuous technical grounds which logically made no sense, the court favoured a tenuous verdict against Commodore, which they simply couldn’t afford to pay. Some say this was the final blow for Commodore, but they were already on unstable ground by this point. 1993 had seen the company lose an astonishing $356 million dollars, and even though the CD32 was selling well, their Philippines stock was held until they could make payment. Despite this, almost 100,000 machines were sold in Europe outselling its rivals, with demand still going strong into 1994, but Commodore simply ran out of units and with component supply problems and mounting debts, simply couldn’t make any more.

Now when you consider some of the finest, ground-breaking and innovative games the platform had witnessed had also come during these years, with software houses like Team17 churning out a record 9 times in 1993 and sharing publisher of the year award with Electronic Arts, its easy to become a little sad and somewhat miffed at the sate of the Amiga’s proceedings by this point. But how did we get here? How had the Amiga gone from such promise to such a low in a short space of time?

There are two ways of looking at this, both are valid, and both played their own part. The first is in the hardware itself; the very thing that had provided the Amiga with so much promise from the beginning. The custom chipset helped career the technology above the Mac and other computers of the time by offloading much that others coded into software, but it also locked the engineers into a narrow specification of what they could change and what they couldn’t. For example, the NTSC & PAL resolutions were a sticking point of the technology and the chip research team just didn’t have the funding to make the jumps they needed. Not only this, but being tied to Motorola processors, the very core of the technology was out of their hands. Whilst Intel created faster and faster chips that could be plonked into IBM PC Compatibles, Motorola struggled to keep up, bailing completely on the 68000 line in 1994 and choosing to enter a partnership with IBM and Apple to develop PowerPC hardware. It’s hard to see how any competitor could have fought off the emerging dominance and economies of scale brought about by the IBM Compatible. The Amiga’s days as a gaming platform were pretty much numbered with the arrival of Doom in 1993 and immersive CD-ROM based games like Myst which turned the glare of many a gamer.

The other way is by looking at the management, and its a view which is tied in to the hardware development. In various conversations David Haynie has expressed how the funding just wasn’t in the right places. The Triple A architecture took some 5 years to almost complete before being dropped. A staggering waste of money that could have been condensed into a shorter time scale and ensured the Amiga’s future from the outset of the 90s. Haynie talks about how the successful engineering management team was replaced by a bunch of idiots by 1991. The same idiots who thought up the Amiga 600, which David Pleasance described as an absolute shambles and waste of time, and the same people who intentionally delayed the AGA chipset. Layer upon layer of bad decision was made, mainly from Irving Gould and Mehdi Ali who seemed transfixed on short term goals and were primarily responsible for the R&D shortages, whilst raking in a huge salary and bonus which could alone have helped the chipset funding massively. Its with a sense of ellipsism that we’ll never know what the Amiga could have been if perhaps Thomas Rattigan had remained at the helm for a few more years.

The last Amiga to roll out from Commodore during March 1994 was the 4000 Tower. A highly upgradable version of the 4000, complete with both SCSI and IDE interfaces and sold as a high end video workstation. However only small numbers were shipped before Commodore International was forced into bankrupty protection on April 29th at 4:10PM, leaving other subsidiaries, such as Commodore UK short on machines and support. The last project demonstrated was the CD1200 prototype at the CeBIT ’94 show which, incorporating the Akiko chip, would have allowed the 1200 to run CD32 games. David Haynie documented the end times of Commodore through his Deathbed Vigil video, which makes for fascinating viewing. The sad news of Commodore International’s demise was further compounded in June when Jay Miner, the father of the Amiga, passed away from heart failure after suffering from kidney complications, his words expressed at the end of the 80s;

[quote style=”font-size:110%;”]”Amiga is so far behind Macintosh and IBM now, and they’ve lost so much

momentum and position, that I think it’s going to be almost impossible to

recover.”[/quote]

seemingly ran true, although he applauded the work David Haynie and the crew had managed to complete with the AGA enhancements against the odds of their management.

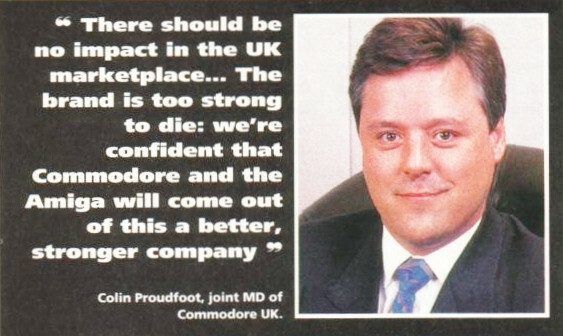

In spite of this wave of sad news, the shining light of Amiga, Commodore UK, was actually still solvent, and it didn’t take long for joint directors David Pleasance and Colin Proudfoot to announce they were looking to buy out the remaining trademarks and assets of Commodore themselves, which included 3,300 CD32’s still sitting in the Philippines and valued at just $22.50 each. A glimmer of hope spread through the Amiga community, with Colin commenting;

[quote style=”font-size:110%;”]”There should be no impact in the UK marketplace… The brand is too strong to die: we’re confident that Commodore and the Amiga will come out of this a better, stronger company.”[/quote]

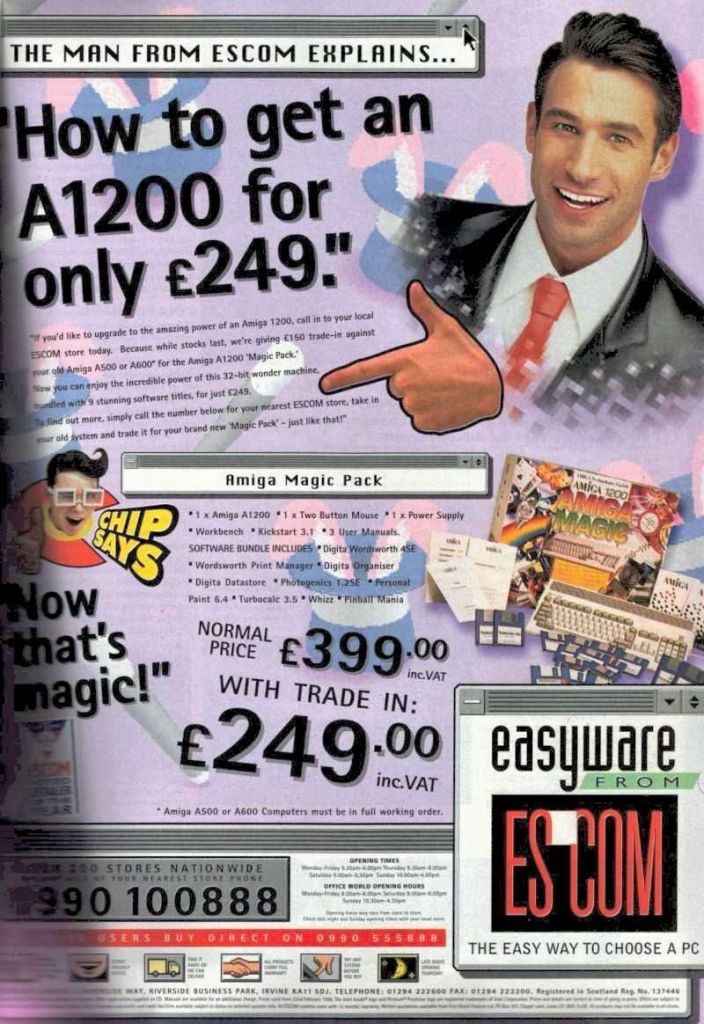

The duo’s plan was to initiate a management buyout and operate the company under the name “Amiga International”, however as 1995 chugged over, it was apparent that there could be other cash rich bidders including IBM, Dell, Creative Equipment International, Samsung and Escom. Dell and CEI came close to what was described as a hideously complex morass of companies spread over several businesses, but almost a year after delcaring bankruptcy on 20th April 1995, it was the PC brand Escom, who picked up the core Commodore business for some $11 million after bids from other companies were ruled invalid. Escom weren’t a company adverse to risk and shunning convention had recently announced it would be shipping OS/2 as the standard Operating System on all their PCs rather than Windows. They were also in the fairly unique position of having a chain of retail shops across the UK and Germany, which could be used to sell their new stock. Pleasance and Proudfoot backed down after it was apparent they couldn’t match the bid and instead agreed to work alongside Escom to establish a future for the Amiga.

Enter the Man from Escom

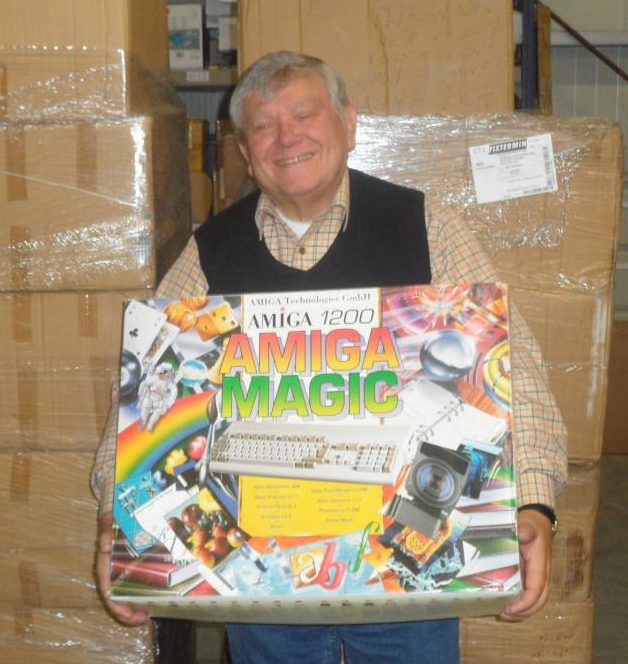

[dropcap style=”font-size:300%;color:#9b9b9b;”]A[/dropcap]lmost immediately afterwards, Escom announced their plans to resume production of the AGA machines via. a manufacturing plant in China. A point which raised concern for some given China’s human rights record and the not so distant memory of Tiananmen Square in 1989. The re-badged Commodore brand was put to use on a new line of PCs and Amiga was split into a new subdidiary called Amiga Technologies GmBH, headed by a number of ex-Amiga people including Jonathan Anderson. Escom took on some 100 ex Commodore staff in total and began work on re-packaging the products and brand.

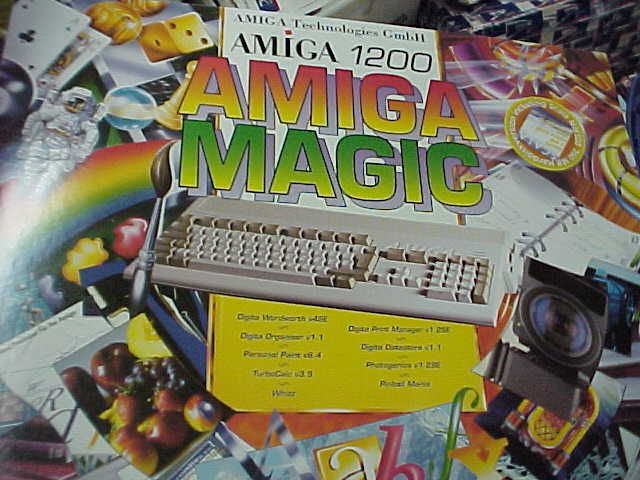

By October, the Amiga Magic Pack was unveiled, consisting of re-badged Amiga 1200 along with Wordworth 4SE, Datastore 1.1, TurboCalc 3.5, Photogenics 1.2SE, Personal Paint 6.4, Organiser 1.1, Pinball Mania and Whizz. It was an all encompassing bundle, but lacked the stand-out games from the Amiga packs seen under David Pleasance’s leadership. The price was also back up to the original launch price of £399 or £499 with a 170MB hard disk, although there was still a relatively high demand for the machine, especially for users who had experienced the Amiga 500 either from new or through the expansive 2nd hand scene. Despite all this, it felt like things would never be like they were and that Amiga Technologies were perhaps driving down a path of expansion and destruction. By late 1995 Amiga enthusiast Petro Tyschteschenko had taken over as CEO and president and there was also talk of pushing out an Amiga RISC PowerPC variant, possibly based on the Hombre chipset that would have included powerful 3D capabilities and could have re-ignited the Amiga brand. However you have to ask, due to the complete hardware re-work, would it have really been an Amiga at all?

Surprisingly, software and add-ons were still appearing from third parties. The CD32 SX add on had launched in late 1994, allowing the CD32 to operate as a fully fledged Amiga, and an entire range of Doom clones was hitting the scene demonstrating the love and determination for many to hang onto their beloved Amiga. Ironically, a community which perhaps wouldn’t have been quite so prevalent had Commodore done their job properly in the earlier 90s, with many software houses, homebrewers and third parties stepping up to fill the gaps which Commodore had left or simply neglected to fill.

Early 1996 saw the re-launch of the Amiga 4000 followed by an announcement for the Amiga “Mind Walker”. This was the only machine which reached the prototype stage under Escom and it combined the AGA architecture, a 68030 CPU and mainstream components including a quad speed CD-ROM, lowering the cost and allowing for expandabiltity, despite it’s inhibitive appearance. However, just like Commodore, Escom entered liquidation a few months later. At one point VISCorp looked like it would buy the Amiga for use in set top box technology but this fell through as they seemingly went under as well.

It seemed like everyone around the Amiga was falling, and not only the companies looking to invest. Long running magazines were coming to an end, and although games were still shipping out from loyal software houses, it was at a certainly slower rate than previous years. Despite this, those Amiga users who had upgraded and were holding on tight bore witness to some impressive games designed specifically for accelerated machines, including Alien Breed 3D II and Nemac IV. Even Myst finally made an appearance, followed incredibly by both Doom and Quake conversions after the source code was released, but these were really the last glimmers of hope for the hardware.

Previous Escom manufacturer Quikpak were the next company interested in purchasing the Amiga, and Dell were again on the prowl but were beaten to the post by Gateway 2000, who were seeking to snap up the intellectual property of some 47 patents held by the existing company. Gaining the following of the existing Amiga owners was a bonus, especially when you consider that Amigas were still swapping hands second hand and in active use. This is how I got my own Amiga 600 in early 1995, although I’m one of the people who quickly switched to a PC before the year was out. Under Gateway, the separate Commodore brand was sold to Tulip Computers, Amiga Technologies was renamed to Amiga International and Petro remained at the reigns. At the World of Amiga ’97, the company then announced they would be developing a new version of the AmigaOS which finally emerged as AmigaOS 3.5 in 1999 under a new subsidiary, Amiga Incorporated. A promise was also made to build – or at least licence out – the Amiga PowerPC once again.

These licencing deals led to Amiga Technology appearing in a range of devices and clones under the “Powered by Amiga” logo still sporting the aging AGA technology, with Power PC boards also arriving around the same time. Pre 1993 ROMS and material were licenced to Cloanto who still sell emulation packages along with videos from the early Amiga scene. In 1999 Gateway retained the Amiga patents but sold Amiga Incoporated itself to Amino Development for almost $5 million dollars, who renamed themselves to Amiga Corporation, whilst retaining the Amiga Incorporated Subsidiary, bringing it satisfying back to the company name first used by Jay and the team back in the early ’80s.

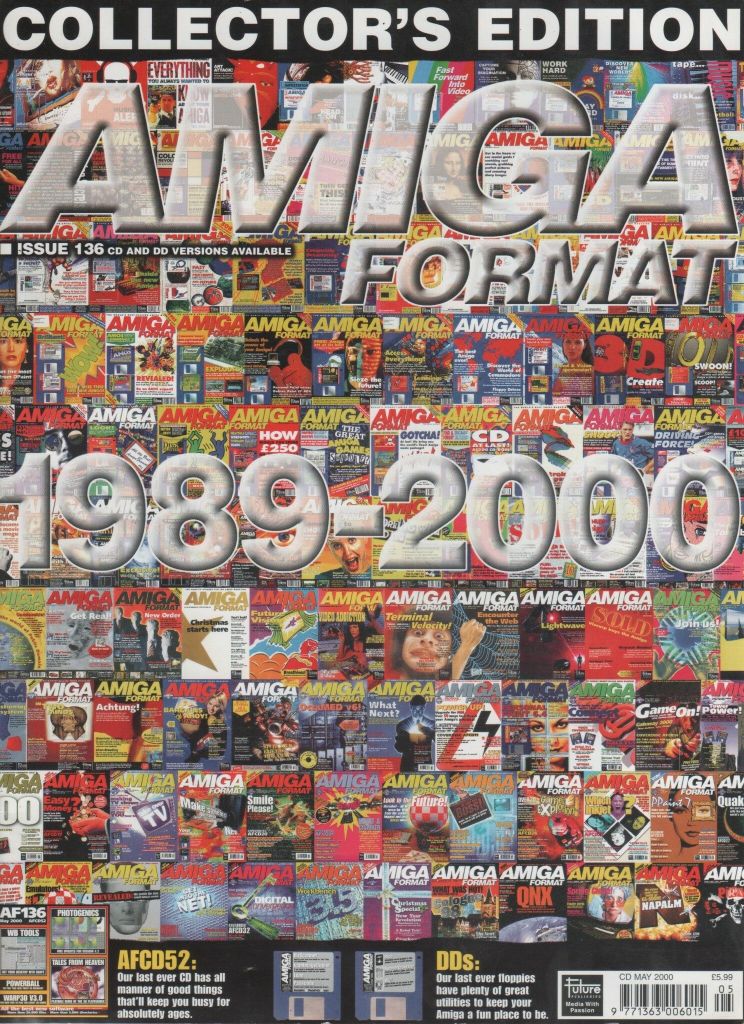

By May 2000 the stable of the Amiga community, Amiga Format published its last issue. Drawing to a close, for me at least, the original days of the Amiga. But its not the end. The period up until now including the contracted development of Amiga OS4 by Hyperion Entertainment in 2004 is worth an entire documentary in itself. With various Power PC variants shipped under the Amiga brand, a host of new accelerator cards, including the lightning quick Vampire II for the Amiga 600, the Armiga system and a massive emulation scene that encompasses both the 68k and Power PC technology. Amiga Incorporated would also move one last time under the ownership of KMOS Inc where it merged into the Amiga Inc name.

But its not just there where we see the Amiga continuing. The influence of Amiga is evident in the very machines we use today. Even after the release of the first AmigaOS, both Microsoft and Apple were watching and implementing features into their own operating systems. The Amiga’s unique design itself inspired countless engineers and the games we witnessed on the platform leave a burning ember with the titles of today. Worldwide the Amiga sold somewhere between 5 million and 10 million units in total, with the last roughly accurate figures clocking in at about 5 million machines at the end of 1993. The Amiga’s significance to modern computing is rooted very much in its past, but love for the brand and hardware are still driving innovation to this very day, and the Amiga scene although a little different, is just as alive today as it was way back in 1992.

And there we go. That was the Amiga Story. I hope you enjoyed it. I thank you very much for watching, and I bid you good night. If you want to subscribe, contribute to the channel, share or give it a thumbs up before you go, then its hugely appreciated, and remember.

Only Amiga made it possible.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.