Dragon. A legendary creature, typically scaled or fire-spewing, with serpentine, reptilian or avian traits. A mythical beast, rarely seen, but often talked about in folklore and tales of heroism.

To all intents and purposes, the story isn’t much different for the Dragon 32 home computer. Announced by Dragon Data in June and launched in August 1982, poised and ready to compete with other micros in the booming UK computing industry. A welsh entrant into an area dense with Cambridge and Oxford based micro industries. The pride of it’s origin is clear in the name of both the company and the machine born from it.

Before we delve into the details of this almost mythical machine, let’s set the scene, starting with the fledgling home micro era of the early ’80s.

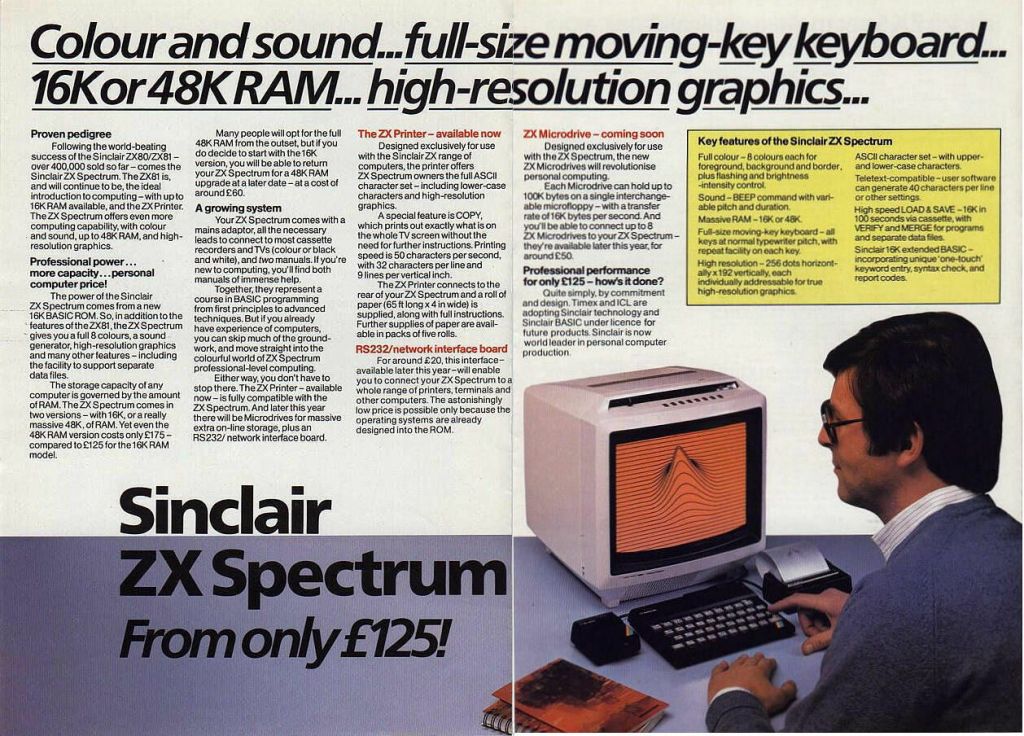

This was a time of excitement. A time of innovation, and this was no more apparent than with the Sinclair ZX80 and ZX81 computers. Produced by Clive Sinclair, these machines were designed to weave their way into homes throughout and country and establish the home computer as a necessity, rather than an obscurity. The root to this was to piggy back on the excitement of the new technology whilst offering a price many could afford. The machines did their job and sold in reasonable numbers, but the landscape was evolving at a significant rate. Over in the United States, machines like Tandy’s TRS-80 were sapping up the market, along with Commodore’s Vic-20 and on the wind was a whispering of a new 64KB machine straight from Jack Tramiel’s drawing board.

Sinclair needed to innovate, both to improve on earlier technology and stave off competition from the likes of Acorn’s BBC Micro and the plethora of other home micro companies wanting a slice of digital pie. Unveiled in April 1982, the Sinclair Spectrum did just that. Offering a “full colour” home micro for less than £150 and with the scope for advanced software and games alike. But Sinclair wasn’t known for fast shipping, and it would take a good 6 months for the Spectrum to start shipping out at an acceptable rate.

In these early technological days, 6 months was a lifetime, and several machines would emerge whilst customers were still waiting for their Spectrums to arrive. These included the Grundy NewBrain, Jupiter Ace and Dragon 32 in the UK alone. Whilst the Commodore 64 and Franklin ACE stepped out in the States and the Sharp X1 and Fujitsu FM-7 in Japan. There was still a lot to play for.

With each new machine that popped up, there was a company behind it pushing their talents, eager to make a mark, and Dragon Data were no different. The original Dragon 32 plan had been laid out by Swansea based Mettoy. Mettoy had been founded in 1933 by Philip Ullman. Originally, he founded a German tin-plate toy company called Tip & Co but escaped to the UK during the rise of the Nazis and used cash owed to him by Marks & Spencer to setup the new organisation. Originally located in Northampton, it relocated to Wales in the 50s and began distribution of railway construction and model kits. During the 70s it was large enough to expand out into the new world of computing and setup an offshoot called Dragon Data, established to help process data for smaller companies. Noticing customers frustration at the slow pace of delivery from computer manufacturers in the early 80s, Dragon Data saw an opportunity to launch it’s own micro and set to work in early 1982.

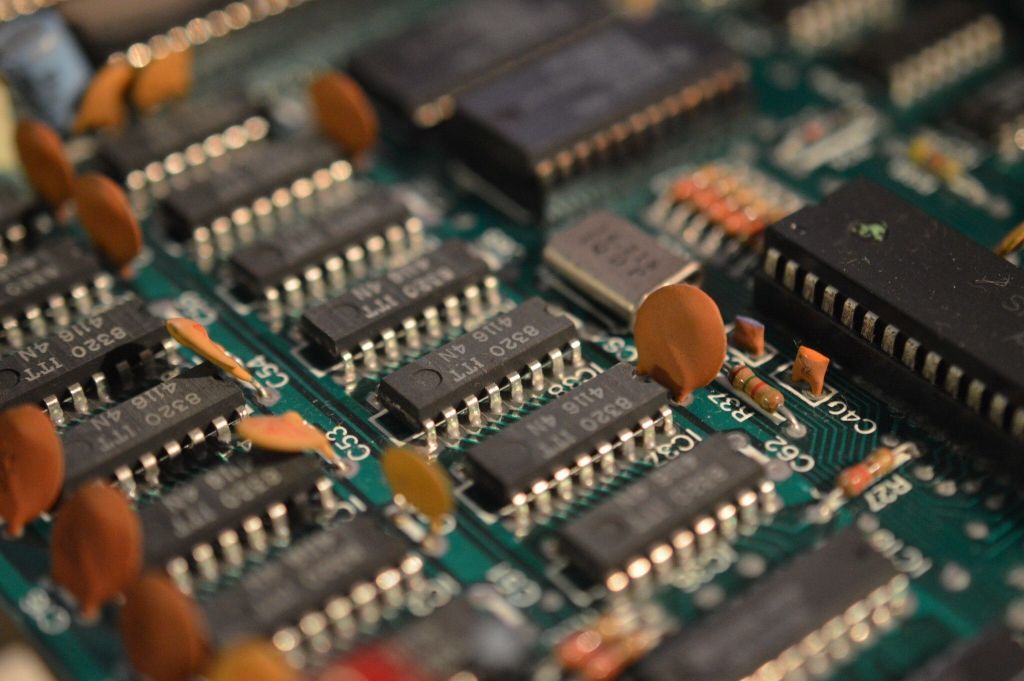

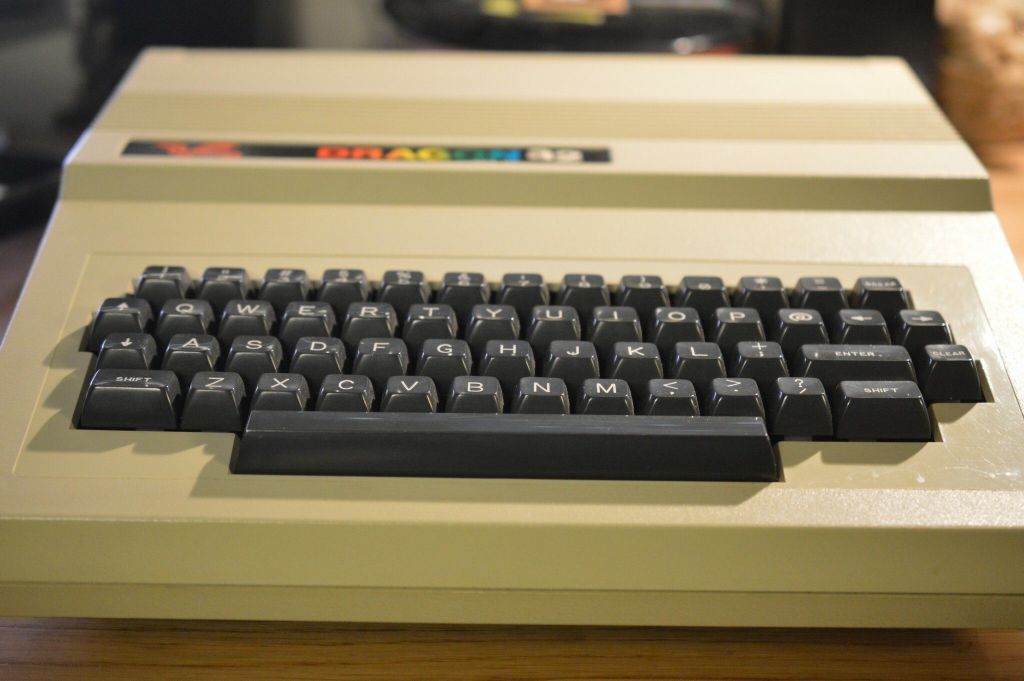

As 1982 progressed Dragon Data were optimistic about their new machine. Sinclair’s Spectrums were shipping at a very slow rate, and Dragon had already agreed astute terms to stock their micros in Boots chemist stores, throughout the country. The system was based around very similar technology found in the TRS-80 Colour Computer – affectionately known as The CoCo. This meant that development could be swift and the machine’s announcement in June, to launch time in August was completed in just 2 months. The specifications for this Welsh beauty weren’t ground breaking, but they were still more sophisticated than a lot of the then competition. Consisting of;

A Motorola MC6809E clocked at .89MHz. This was an 8 bit CPU, but it contained many 16 bit design elements and could beat off machines based on the MOS 6502 in terms of raw computational power.

An MC6847 chip generated the video display of 256 pixels by 192 lines in monochrome or up to 128×192 with 4 on screen colours. With a nine colour palette, it’s responsible for the garish colours seen on the Micros it inhabits

Sound is served up with 1 voice and 5 octaves in BASIC and 4 voices with 7 octaves via. machine code

32KB of RAM was provided – this was initially 16kb, but after getting wind of Sinclair’s proposed 48k Spectrum, was upped to 32.

16KB of ROM housed Microsoft Extended BASIC

Port wise, the machine has a number of quirks. First it features an analogue joystick port, allowing for versatility, and light pen adoption.

Second, unusually for this era, there’s a monitor out, providing a composite image, which can be used with modern LCD screens.

There’s also a tape connector, ROM cartridge input and scope for an additional accessory called the “Dragon’s Claw”, allowing you to use BBC Micro peripherals with your Dragon machine.

To differentiate the machine from the CoCo and avoid legal action, a number of improvements were also made; the first was the increase in memory; base CoCos only shipped with 4KB of RAM, with machines only accommodating a cut down Microsoft BASIC, however, the Dragon could pack the powerful extended Microsoft BASIC from the go in it’s spacious 32KB of RAM. The monitor port and full parallel port was also included, allowing fast, standardised printer communication, and something of a rarity among 8 bit machines. When you first boot the Dragon, you’ll see the the initials DNS, these were added by it’s programmer Duncan Smeed to the somewhat borrowed Tandy ROM. The Dragon was based on a reference design from Motorola, produced as an example of the MC6809E’s capabilities, but Motorola were more than happy to help, knowing they’d get more sales from the leak of information.

The machine also has a power switch and reset button, features often omitted on machines of the time, with many regarding the power socket switch as a suitable current eliminator.

Like the TRS-80, CoCo and indeed other machines such as the Texas TI99, the limitations of the ROM meant the machine was unable to display lower case characters. This wasn’t a problem for gaming use, but it severely impacted their penetration into educational and business markets, which was a shame given some of the more suitable technical quirks. Still, as standards of the day went, it was a reasonable machine.

The Launch

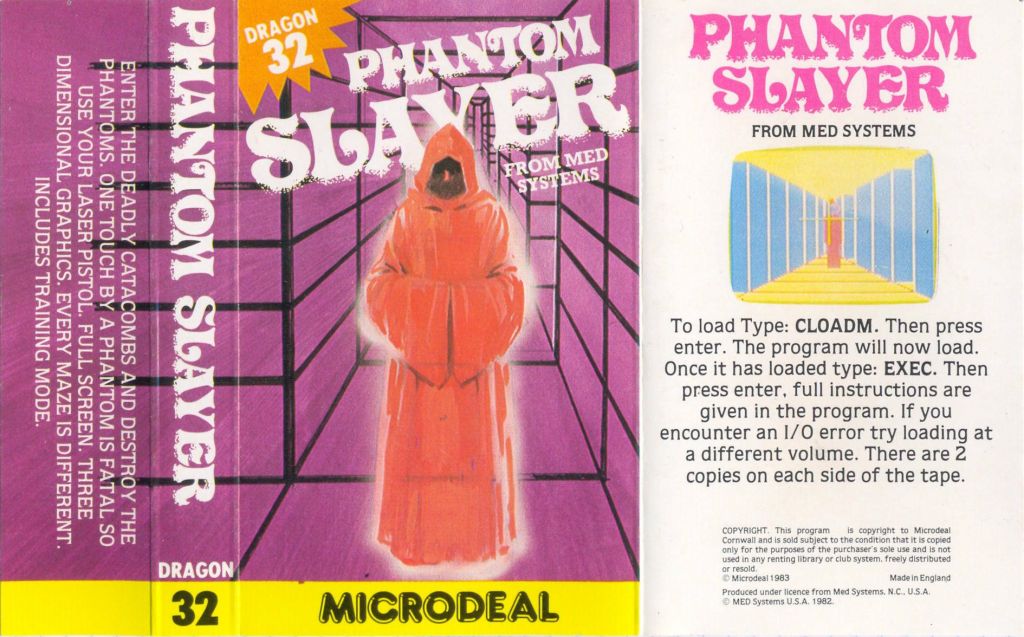

It’s August launch date and almost immediate availability in high street shops attracted a spike of interest, with several independent software developers jumping on board including Microdeal who had experience with Tandy’s CoCo. The magazine, Dragon User also emerged quite quickly providing promise for the Welsh machine. As this was an era where new machines could appear and disappear with hardly a recognising nod, these early signs bode well for Dragon. As well as selling well among Welsh inhabitants, the Dragon 32 fitted into an area of the market that was cheaper than the BBC Micro, but not too overpriced that it put off potential Sinclair customers, selling for a reasonable £175. It also possessed the rugged look of Acorn’s BBC machine, with a real keyboard and large plastic case capable of supporting a monitor or small television. If you were looking for a well built machine with room for expansion, then the Dragon seemed a good direction to go in. Pushed on by favourable reviews, Personal Computer News charted the machine as the 3rd best seller on September 15th 1982 and it would go on to sell over 40,000 units before 1982 was out. Supply was outstripping production.

TAKE OVER, THE BREAK’S OVER

However as 1982 drew to a close, Mettoy’s financial situation was looking dire. It’s core toy business had been losing money at an increasingly frantic pace and this was affecting Dragon Data’s finances. Despite the Dragon 32’s success, banks were unwilling to provide finance admist an increasingly saturated micro market. Managing director Tony Clark began discussions with various companies and institutions for re-financing options. The Welsh Development agency bought a 23% stake, and Pru-tech, the high-tech investment arm of Prudential Insurance snapped up 42% and the controlling stake. Mettoy were left with just a 15.5% share, but this enabled Dragon Data to continue development and contract out Race Electronics to assist with delivery demand. Part of the deal with the Welsh Development Agency was also to move to a larger manufacturing premises at Kenfig, near Port Talbot. Of course this made sense, but large overheads are only good when large demand is present.

The input of investment shifted Dragon Data to become the largest privately owned company in Wales and the increased production allowed chains such as Dixons and Comet to begin stocking the popular machines. 10,000 Dragon machines were being produced per week, with Dragon Data foreseeing no drop off in their fortune, even in the wake of the Sinclair Spectrum and Commodore 64 now entering the high street in chains such as WH Smith and John Menzies.

However, there were problems in wait. Some foreseeable, others not.

The first was the specification. The CPU was pretty powerful compared to the Z80 and 6502 chips found in Spectrum and Commodore machines, but it wasn’t mainstream. We all know that success often lies with third party development, and due to the painful process of having to re-write games from other platforms from scratch, many didn’t bother, with exceptions like Memotech already having a line of software for the virtually identical CoCo. Talking of platforms, other machines had better graphic and text support, with the Dragon built on hardware that was now, some 3 years old. In high resolution mode, the Dragon could only display 2 colours, and only 4 on screen in standard resolutions, coupled with this, it couldn’t combine text and graphical modes, further adding to development woes. Other contenders had also began to pop with with the likes of the Oric-1 and Memotech MTX. This led to increased market saturation with the Commodore 64 and Spectrum emerging as the dominant force, the latter now selling 16KB models for under £100! Suddenly, combined with the summer lull those 10,000 units being produced per week started to stack up in warehouses. The shine was again starting to look rather grim and Dragon’s advertising pretty much telling buyers to leave the coding to experts didn’t help matters.

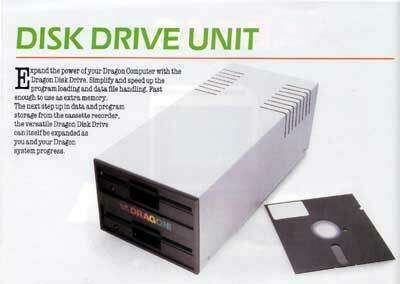

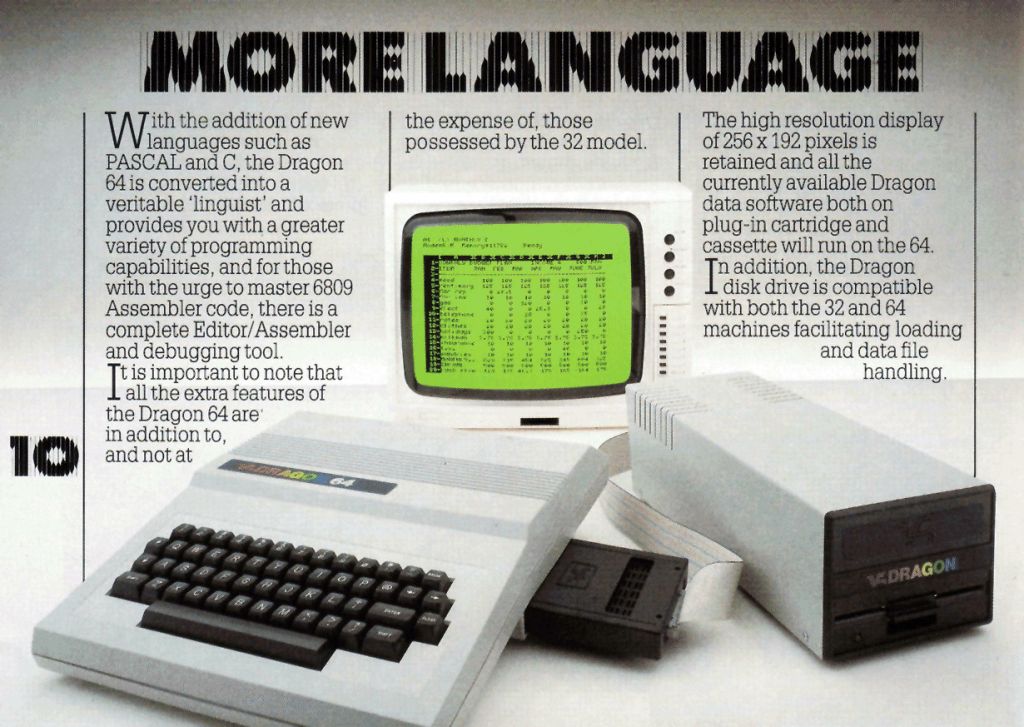

Not in their nature to be pessimistic, Dragon Data continued planning out a line of expansions. The first was a 5 1/4″ DragonDOS based disk drive, the second was a new OS-9 Operating System licenced from Microware Systems and the third was a 64KB RAM upgrade and subsequent standalone system. The disk drives were planned for April, but arrived in September at £275 or £475 for twin drives, unfortunately not before a third party, Premier Delta had launched their own. It seems the delay was costly as the Delta operating system was generally deemed superior to DragonDOS and took a greater market share.

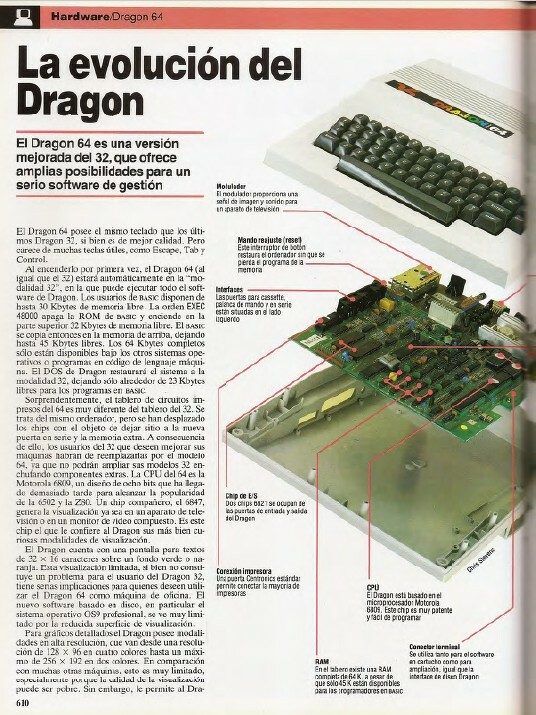

The 64KB RAM upgrade, which was initially announced as a single board swap for £75 was advertised as a £100 whole lower case swap by May, offering an additional RS232 interface and second BASIC ROM, essentially converting 32 systems to the same specifications as the anticipated Dragon 64. The second ROM allowed booting in 64KB mode by shifting the BASIC to occupy the upper 16KB of RAM, but oddly meant the disk drive functionality was unavailable as it mapped into the cartridge port’s RAM space. However 32 owners wouldn’t see any such upgrades this year.

Dragon also announced the new Dragon 64 would arrive on US shores, distributed and ultimately manufactured by Tano Corporation. Dealers were anxious about the price war between Commodore, Atari and Texas in the states and it was believed a robust, reliable system like the Dragon could deliver higher profit margins, therefore spiking interest in retailers. Launching before the UK on 26th August at $399 it also bundled with a spreadsheet, mail-merge and wordprocessor. Dragon announced that two further systems were in the pipeline, the first being a direct competitor for the higher end BBC model B hardware and the second a full blown business system aimed to compete with the IBM PC. It seems an amalgamation of these was prototyped the following year, featuring two MC6809E processors, a numeric keypad, 128KB or 256KB of RAM and the new OS-9 but it never made it to market.

Back in the UK, the US deal didn’t help managing Director Tony Clarke. Now sitting on a mountain of unsold Dragon 32s, shareholders gave a helping nudge and Tony left the company for “personal reasons”. On September 12th, Prutech, who also held the major share in General Electric Company asked Brian Moore, the GEC deputy director to take over the reigns at Dragon Data along with a £2.5 million investment to keep the company moving forward, this saw GEC effectively take over control of Dragon, working out perfectly, as GEC were keen to enter the home micro market themselves by now. With 80,000 Dragon 32s sold to date, it was hoped the Christmas period would shift most of the excess stock.

But before Christmas would arrive, Mettoy, the instigator of the Dragon, and still a 15% shareholder had to call in the receivers. It’s overall toy line just wasn’t performing and a management buy out led to the formation of Corgi Toys Limited. Prutech upped it’s shares to 49% at this point and made sure to push the message home that Mettoy’s demise would not effect the ongoing operation of Dragon Data and it’s expanding computer line.

Ever keen to push forward, the grey Dragon 64s appeared in November with more pleasing keyboard aesthetics, sporting a smaller font (Although still lacking a lower case mode). Also it was just in time for Christmas, priced at £225, and poised to demonstrate that the Dragon brand was still strong and going places. The 64 was well received over this period, both in the UK and US operations after being promoted at the Color Computer Expo in Pasadena. The French arm of Dragon was also in it’s infancy at this point and by Christmas 1983, had shipped 20k Dragon 32s themselves.

As 1984 rolled around, the 64KB upgrade for 32 owners was still not in sight, but a new plan was put into motion. Users could exchange their 32s for 64s, eliminating the need for modifications or costly technical work, but with the trade in cost set at £140, many users preferred the option of selling their current 32 models and simply buying a Commodore 64, whilst still having cash to spare. It had also become apparent that some software would no longer function on later revisions of the 32. Coders had cunningly found a “speed up Poke” early on which allowed overclocking of the processor to a whopping 1.8MHz, however newer machines seemed to have lower tolerances, possibly due to lower quality components which would not operate with this poke. Games such as “Up Periscope” and “Flight Simulation” just refused to work. Consumer patience was being tested and allegiances were falling stray with even more machines entering the market.

Owners of Disk Drives would be graced with the somewhat late arrival of OS-9 by March offering multi tasking, resource sharing over networks, file ownership and even the possibility of a graphical user interface. For £40 you got the single 5 1/4″ floppy and a manual with additional applications such as the Stylograph word processor, Dynacalc spreadsheet and RMS database available for between £55 and £80. Drive owners were keen to snap the software up, providing the machine some added life with various programming languages available for the operating system. It would later transpire that Dragon, now known as GEC Dragon, never actually paid a licencing fee to Microware, likely due to the troubles on the horizon.

Over the next couple of months GEC would push more professional advertising out for the Dragon machines with double page spreads selling the perks of the computer with potential promised printers, monitors and cassette decks on the way, and new machines even promised. The first was a transportable 64K machine expected to include a modem, 3.5″ Sony disk drive and reported to be compatible with previous Dragon hardware. This machine was called Project Alpha and demonstrated at the Consumer Electronics Trade Exhibition in May. The 3.5″ drive also seems to point at GECs desire to launch an MSX compatible system in the UK. MSX was an attempt to standardise 8 bit home computers, emerging in Japan (you can watch my MSX video to find out more), and as part of that standard the new Sony 3.5″ disk drives had taken precedent over Hitatchi’s 3″ drives. It seems likely that this Alpha system was a middle step on the road to MSX. The other new machine, called the Beta machine, was the souped up amalgamation of the systems announced the prior year.

However, at the same time these machines were being exhibited. Dragon Data had some problems. A month prior BHS had slashed the prices of it’s Dragon 32 stock to £87.50, as they cleared shelves to stock a competitor machine. Boots had also cut prices and announced they would stop stocking the 32. In reality they were looking to stock the Dragon 64 instead, but it sent a negative message out to the public, and in any case, many saw the 64 as just a slightly expanded 32 in the face of other, more capable machines.

End Times

In wake of declining sales, GEC Dragon went into administration during the spring of 1984, with Tano over in America also stopping support for the dwindling machine. Dixons quickly slashed the price of their stock to £79.99 with a bundle of free software. Dragon 64s were lowered to £169.99 and disk drives for less than £100. As with all price cuts, this actually formed a new wave of users who, unaware of compatibility or ongoing support snapped up the discounted equipment and entered into the new digital age. 100 machines were also given to Weetabix who ran a promotion offering a pretty substantial prize including a Dragon 64, television, disk drive, cassette deck and space invaders type game. To be honest, I’m tempted to try and enter myself, even now!

Software houses like Salamander Software began to re-evaluate and quickly entered talks with Tandy to see if they could sell titles to the American market. Something you question why they didn’t do earlier, especially with a massive market available overseas which required very little work to adapt Dragon software to, given the CoCo’s some 95% compatibility following a few address tweaks. Still they needn’t have worried too much as the UK Dragon user count was over 200,000 at this point. Dragon wasn’t quite dead yet and several bidders would queue up to grab themselves a bargain. One of these was Tandy, who, failing to capture the UK market with their own computers (which were twice the price as Dragon’s offering) saw an easy route in with a largely compatible machine. However they were put off by existing liabilities and outstanding stock, and their bid was rejected by the receivers. This is when the Spanish company Eurohard SA stepped in, offering £1million and securing the company and a portion of it’s existing stock.

Eurohard had actually been in talks with Dragon before they went under seeking to licence the machines for sale in Spain, and so a cheap buy-out made perfect sense. The buy-out agreement meant GEC would continue marketing in the UK, and a new company, Touchmaster, backed again by Pru-tech, would provide after sales support. Touchmaster took up residence at Dragon’s site in Port Talbort, consisting of mostly the same employees. A new deal was then forged with Comet to take existing stock and Dragon 64s were soon selling for just £130. This swelled the user base, further sparking a resurgence that would last for the next few years.

The mid decade based year of 1985 was looming and over in Spain Eurohard had embarked on a BBC Micro inspired idea, with the assistance of the Spanish government, to sell their newly named Dragon 100 and Dragon 200 machines alongside an educational television show that would air in schools and would introduce the country to the wonderful world of 8 bit computing. Eurohard had purchased 13,000 Dragons as part of their takeover and were selling at £200 for the 100 and £300 for the 20 model, they also began production at their own plant in Caceres.

Keen to expand on Dragon’s MSX ideas they also signed an agreement with Microsoft to be one of the first distributors of MSX machines in the West, producing the Dragon MSX prototypes in May 1985. Based around the MSX architecture, these were of course, incompatible with the earlier Dragon machines, however on selling only 17,000 standard Dragon machines in the Spanish home market – less than anticipated – and giving away another 20,000 to schools and institutes through the Government subsidy programme, Eurohard were unable to expand further and production of the new MSX range ceased.

Back in the UK, Eurohard had appointed Compusense to try and shift further Dragon units from their own stocks, but the software market was starting to crumble. Websters, one of the biggest distributors had ceased handling Dragon software whist the long-standing Dragon User magazine was forced to switch to subscription only from June 1986. In May 1987 Eurohard closed up it’s Dragon operations and in January 1988, Microdeal, the original main supporter of the Dragon announced they were pulling out of the market.

This didn’t leave much left for Dragon owners, with the committed Dragon User magazine finally giving up the ghost in January 1989 after being run by Bob Harris for the last 7 issues from his own pocket. Bob had been running Harris Micro Software, one of the most avid and final supporters of the hardware. The last Dragon show was held in September 1994 at a school in Liverpool on the same day as their Autumn fare. Marking the end of this ferocious, mythical beast.

GAMES

But let’s not end on a depressing note. For although the Dragon led a short life, it was a firey one, if a rather vivid green fire at that, but with an admirable collection of games and software. Here are some of my favourite titles on the Welsh machine;

Phantom Slayer is an incredibly early First person shooter. One of the earliest, and the eerie stalking Phantoms, incite a definite feeling of dread.

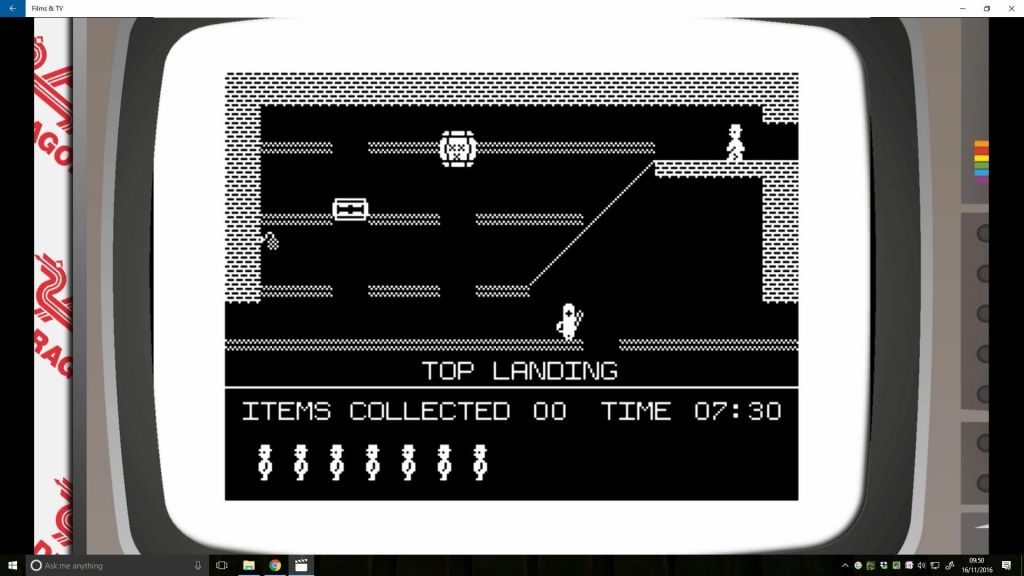

Jet Set Willy is a great conversion of the classic Spectrum game, although displayed in monochrome form due to high resolution requirements.

Chuckie egg, another classic and unmistakably green here.

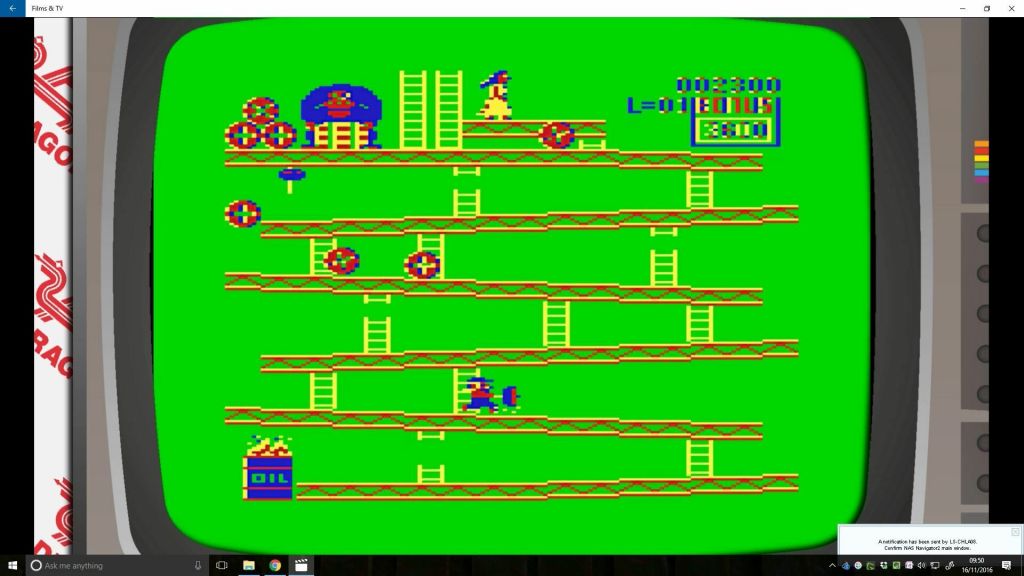

Donkey King is a garish incarnation of the arcade classic. I dunno. There’s just something I love about the garish palette.

Airball sees us in an isometric perspective and it’s a giant leap forward over a lot of previous Dragon games. Later ported to the Amiga, Atari ST and even Gameboy Advance.

Rommel’s Revenge does a grand job of imitating vector graphics, again using high resolution mode, but the alternative and distinctly green monochrome variant. Funnily enough, the Dragon doesn’t actually have black, it’s just a very dark green. So much green.

BackTrack, again I love the colours here. This is a maze game where you have to guide your chappy through various rooms, seeking keys. Marvelous.

and last, is Leggit. Again bright, but using distinctly different hues. I sometimes think that a restrictive palette can bring out the best in a screen. The premise here is to jump through the gaps whilst avoiding enemies and it works beautifully.

So there we go. That was, and indeed is, the Dragon series of computers. The computer that inspired it’s user base, gave us green induced eyestrain, albeit in a pleasing fashion, brought us all a little closer to Welsh rooted micros and reminded us that it’s possible just to hang on in there, despite soaring competition and the waves of obstacles telling us otherwise.

The Dragon legacy lives on through it’s committed fan base, with newer games such as The Glove, a Gauntlet clone, released a few years back. Apparently a company called California Digital bought the remaning Tano Dragon stock and since 2009, you can buy them for $49. Brand new! Although shipping to the UK is about $90.

Thanks for watching. I hope you enjoyed this look into a little known computer of the past. Please give it a thumbs up if you liked it, or down if you hated it. Click a video below, subscribe for more or contribute to my Patreon to support me. In any case, thank you very much for watching and as always, have a good night.

I’d like to take this moment to give a big thanks to John from StigsWorld for helping me with some footage of Dragon machines. I sold one of my machines a while back, so it was a a big help. Please visit his channel at the link below.

Also big thanks to the Dragon Archive for allowing me to borrow some content. If you’re after a vast selection of Dragon internet things, then head to worldofdragon.org

Most of the backing music in this video is by Snowkitten. You can pick up the greatest hits album at snowkitten.bandcamp.com

Massive, massive thank you to every single one of my patrons for making this channel possible. Some of whom’s names are now scrolling across the screen.

God speed, and I’ll see you on the next video.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.

1 Comment

Add Yours →when u say the Dragon was compatible with BBC add-ons do u mean co processors?