Watch the Video

The Amstrad GX-4000 was Alan Sugar’s attempt to enter the game console market during the early 90s. It bombed, mainly due to a lack of games, but also because of the dated hardware used. This video features all the GX4000 games, an introduction to the system and it’s life story. Enjoy!

Alan Michael Sugar Trading Limited (aka. Amstrad) is renowned for following in the footsteps of others, and either improving a product or re-marketing it for an untapped area of the population. They did this with the CPC 464 range by taking a design which was very similar to the Sinclair Spectrum, but then positioning it as an “All in one, easy to use system”, simply by bundling a compulsory monitor with each unit.

Therefore you’d probably expect their first console foray to be a similar affair, however this was not quite the case. The console launched in September 1990, to a reasonably low key delivery by Mr. Sugar (before he was a Lord). During this delivery Sugar was battered with questions over the 8 bit technology of the console amid a market which had now been home to both the Amiga and Atari 16 bit machines for 5 years, and even more recently the Sega Mega Drive. Sugar disregarded these questions with the comment “the technicalities didn’t matter, and it was the product and what it did that counted”, and to be fair, the system did offer capabilities which were above the original CPC range and even surpassed Sega’s and Nintendo’s 8 bit consoles. What wasn’t taken into consideration was the buzz around BITS. The word 16 bit used to strike up images of super graphics, ultra sound and blazing game play. Even by late 1990, 8 bit was starting to look a bit long in the tooth, and regardless of the hardware sprites and extended colour palette utilised by the GX, it was still stuck in the world of 8 bit technology, and as a consequence, suffered.

The console launched at a pretty competitive price point of £99, similar to what the Commodore 64GS would launch for just a few months later. Coupled with this Amstrad launched a massive £20 million pound marketing campaign, alongside the CPC 464 Plus and CPC 6128 Plus models which were launched at the same time (and both featuring the compatible cartridge slot of the GX). This dwarfed the development costs of the console, which are estimated to be below £1 million pounds, having been based on existing technology, and following the traditional Amstrad method of designing the case first, and then manufacturing the components to fit; this lead to a small form factor machine, which looks arguably futuristic and is incredibly light. But even this impressive marketing spend, it was not enough to stop the system from only selling 15,000 units. If you compare this to Sega’s Master System which sold over 10 million units, it’s easy to see that the machine was just too late to market. If only they’d have spent more of that advertising budget on development, we may have seen a drastically different story.

Sadly though, this was unlikely to have happened. Amstrad’s fortunes weren’t what they were at this point in time and Sugar had recently announced an ambitious initiative to produce 1 Amstrad product per month. The GX-4000 was one of these products, and therefore given the time constraints, it was always going to be a “me too” product in a last minute bid to try and get into the console market. It’s a story we’re all too familiar with following Commodore’s 64GS, Amiga’s CD32 and Atari’s Jaguar in the few years following.

The System

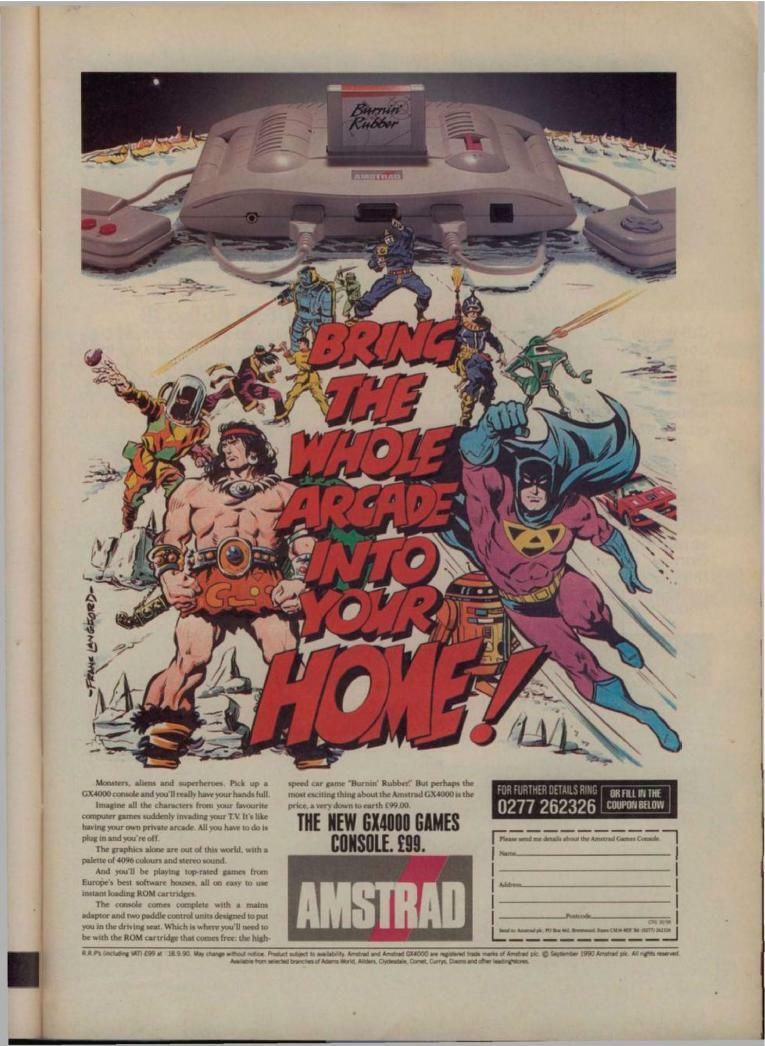

On launch, the system actually gathered some commendable reviews, with the popular CVG magazine describing it as a “neat looking, technically impressive console that has an awful lot of potential for just £99”. Audio wasn’t the best, but the chip was still comparable to what you’d find at the heart of the Atari ST (which although praised for it’s Midi Music capabilities, didn’t actually bolster a very good audio chip). The graphics were the main draw however, with the GX capable of beating off similar priced consoles such as the Master System and NES pretty easily. The tagline for the console played on this with the phrase “Bring the whole arcade into your home!”.

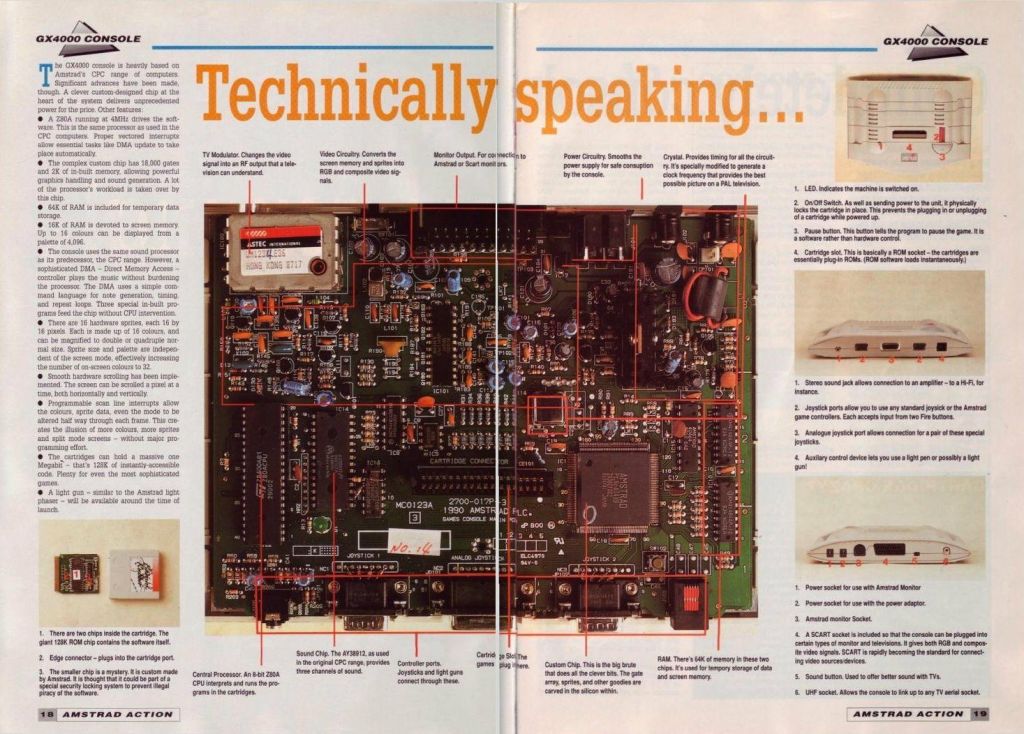

Technically the system boasts;

A Zilog Z80A 4MHz CPU, similar to that found in the Master System

A whopping palette of 4,096 colours, which outstripped even the Mega Drive‘s 512

16 hardware sprites

64KB of RAM

An AY-3-8912 sound chip with 3 channels

A maximum resolution of 640×200 with 2 colours or 160×200 with 16 colours

And… 32KB of ROM

The system also had ports aplenty, with;

An audio output

2 controller ports

An analogue controller port (similar to PCs)

A lightgun port

A Scart video out

RF video out

Power supply from external PSU

And an additional power supply socket from a monitor (if used)

The system’s controllers are very similar to what you’d find with the NES and Master System, in all their rectangular shaped glory.

A quick flick through the manuals gives you the normal gumf, along with IMPORTANT messages such as “treat the controllers with reasonable care”. Pretty subjective, although thankfully they can take quite a battering.

Software

The game line up was sadly another blow for the GX’s launch, with just not enough software available on the £25 cartridge format. Ocean stepped up, as they did with the Commodore 64GS, but many of the games were just direct ports from the CPC tape variants…. people were just not happy to shell out 5 times the cost for a game which had been available for a number of years on an older system. This was a shame, as some developers praised the GX for capabilities similar to the 16 bit Atari, with only the use of blocky colour pixels (handed down from the CPC) stopping it from looking as refined on screen as it’s 16 bit counter parts.

Even some of the bespoke games such as Copter 271 were frankly a bucket load of poo, and the good titles which existed such as Robocop II and Pang, just couldn’t make up for the shortfall.

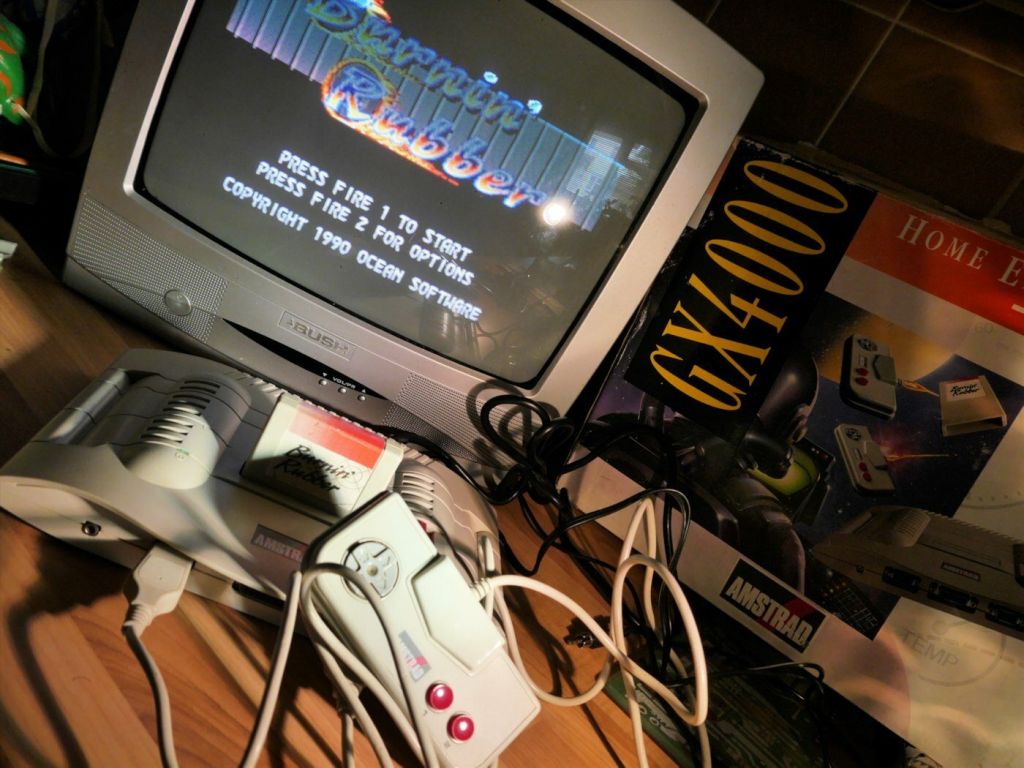

In a bid to win affections, Burnin’ rubber was shipped with every console, to give immediate entertainment out of the box. It’s actually a pretty addictive game, with great graphics (when you compare it to other 8 bit equivalents), excellent sprite scaling and a pretty forgiving steering system, which you can drive with one thumb if you so desire. The only problem with Burnin’ rubber was it’s placement in the box; it was slotted in the base of the Polystyrene, at the bottom of the box. Many customers failed to navigate this packaging successfully and complained about not being able to find it…. XD.

In all; only 26 games were ever made for the machine. So rather than running through my favourites, here’s all of the god damn games in one burst;

Oh, by the way, if you happen to own Chase HQ II, Special criminal investigation for the GX, then look after it. Only two copies are known to be in existence!

The End is Nigh

With the machine being 25 years old, it’s somewhat collectable now, especially given it’s limited manufacturing run. You can even buy a cartridge to slot in and download CPC games to via SD card, much like the EverDrive system on the Sega machines.

The system’s availability in it’s launch countries of Britain, France, Spain and Italy lasted just over a year. With it being discounted to under £80 within 8 months, and disappearing into the midst of time not long afterwards. This also led to some games such as Gazza II never making it into production, although apparently some review code still exists somewhere today. Keep your eyes peeled.

The system’s availability in it’s launch countries of Britain, France, Spain and Italy lasted just over a year. With it being discounted to under £80 within 8 months, and disappearing into the midst of time not long afterwards. This also led to some games such as Gazza II never making it into production, although apparently some review code still exists somewhere today. Keep your eyes peeled.

So then. That was the Amstrad GX-4000. If you get a chance, snap one of these consoles up. Mine originally cost about £30, and given the small size of the software library, they make an ideal collectors piece, even if you’re unlikely to ever own Chase HQ II…. So if that bothers you, probably best not to bother.

Nostalgia Nerd is also known by the name Peter Leigh. They routinely make YouTube videos and then publish the scripts to those videos here. You can follow Nostalgia Nerd using the social links below.

2 Comments

Add Yours →That was fun. One small correction: you mean “late 80s” for 8-bit being long in the tooth, as in the late 90’s we were already tiring of the Dreamcast.

I know nothing of the Amstrad because I live in the US, but I’m sure I would have been tempted by the low prices had it made it over here.

You’re right! I meant late 1990! School boy error!